New Data Center GPU

Oct. 23rd, 2025 03:51 pm Intel unveiled a new data center GPU at the OCP Global Summit this week. Dubbed “Crescent Island,” the GPU will utilize the Xe3P graphics architecture, low-power LPDDR5X memory, and will target AI inference workloads, with energy efficiency as a primary characteristic.

Intel unveiled a new data center GPU at the OCP Global Summit this week. Dubbed “Crescent Island,” the GPU will utilize the Xe3P graphics architecture, low-power LPDDR5X memory, and will target AI inference workloads, with energy efficiency as a primary characteristic.As the focus of the Gen AI revolution shifts from model training to inference and agentic AI, chipmakers have responded with new chip designs that are optimized for inference workloads. Instead of cranking out massive AI accelerators that have tons of number-crunching horsepower–and consume heaps of energy and produce gobs of heat that must be removed with fans or liquid cooling–chipmakers are looking to build processors that get the job done as efficiently and cost-effectively as possible.

That’s the backdrop for Intel’s latest GPU, Crescent Island, which is due in the second half of 2026. The new GPU will feature 160GB of LPDDR5X memory, utilize the Xe3P microarchitecture, and will be optimized for performance-per-watt, the company says. Xe3P is a new, performance-oriented version of the Xe3 architecture used in Intel’s Panther Lake CPUs.

“AI is shifting from static training to real-time, everywhere inference–driven by agentic AI,” said Sachin Katti, CTO of Intel. “Scaling these complex workloads requires heterogeneous systems that match the right silicon to the right task, powered by an open software stack. Intel’s Xe architecture data center GPU will provide the efficient headroom customers need —and more value—as token volumes surge.”

Intel launched its Intel Xe GPU microarchitecture initiative back in 2018, with details emerging in 2019 at its HPC Developer Conference (held down the street from the SC19 show in November 2019). The goal was to compete against Nvidia and AMD GPUs for both data center (HPC and AI) and desktop (gaming and graphics) use cases. It has launched a series of Xe (which stands for “exascale for everyone”) products over the years, including discrete GPUs for graphics, integrated GPUs embedded onto the CPU, and data center GPUs used for AI and HPC workloads.

Its first Intel Xe data center GPU was the Ponte Vecchio, which utilized the Xe-HPC microarchitecture and the Embedded Multi-Die Interconnect Bridge (EMIB) and Foveros die stacking packaging on an Intel 4 node, which was its 7-nanometer technology. Ponte Vecchio also used some 5 nm components from TSMC.

You will remember that Argonne National Laboratory’s Aurora supercomputer, which was the second fastest supercomputer ever built when it debuted two years ago, was built using six Ponte Vecchio Max Series GPUs alongside every one Intel Xeon Max Series CPU in an HPE Cray EX frame using an HPE Slingshot interconnect. Aurora featured a total of 63,744 of the Xe-HPC Ponte Vecchio GPUs across more than 10,000 nodes, delivering 585 petaflops in November 2023. It officially became the second supercomputer to break the exascale barrier in June 2024, and it currently sits in the number three slot on the Top500 list.

When Aurora was first revealed back in 2015, it was slated to pair Intel’s Xeon Phi accelerators alongside Xeon CPUs. However, when Intel killed Xeon Phi in 2017, it forced the computer’s designers to go back to the drawing board. The answer came when Intel announced Ponte Vecchio in 2019.

It’s unclear exactly how Crescent Lake, which is the successor to Ponte Vecchio, will be configured, and whether it will be delivered as a pair of smaller GPUs or one massive GPU. The performance characteristics of Crescent Island will also be something to keep an eye on, particularly in terms of memory bandwidth, which is the sticking point in a lot of AI workloads these days.

The use of LVDDR5X memory, which is usually found in PCs and smartphones, is an interesting choice for a data center GPU. LVDDR5X was released in 2021 and can apparently reach speeds up to 14.4 Gbps per pin. Memory makers like Samsung and Micron offer LVVDR5X memory in capacities up to 32GB, so Intel will need to figure out a way to connect a handful of DIMMs to each GPU.

Both AMD and Nvidia are using large amounts of the latest generation of high bandwidth memory (HBM) in their next-gen GPUs due in 2026, with AMD MI450 offering up to 432GB of HBM4 and Nvidia using up to 1TB of HBM4 memory with its Rubin Ultra GPU.

HBM4 has advantages when it comes to bandwidth. But with rising prices for HBM4 and tighter supply chains, perhaps Intel is on to something by using LVDDR5X memory–particularly with power efficiency and cost being such big factors in AI success.

Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) is laying off 4% of its global workforce, around 1,000 employees, as it pivots resources to developing AI-focused chips. This marks a strategic shift by AMD to challenge Nvidia’s lead in the sector.

Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) is laying off 4% of its global workforce, around 1,000 employees, as it pivots resources to developing AI-focused chips. This marks a strategic shift by AMD to challenge Nvidia’s lead in the sector.“As a part of aligning our resources with our largest growth opportunities, we are taking a number of targeted steps that will unfortunately result in reducing our global workforce by approximately 4%,” reported quoting an AMD spokesperson.

“We are committed to treating impacted employees with respect and helping them through this transition,” the spokesperson further added. However, it remains unclear which departments will experience the majority of the layoffs.

The latest layoffs were announced as AMD’s quarterly earnings reflected strong results – a strong increase in revenue as well as net profit.

This surprised many in the industry. Employees too demonstrated their shock in community chat platform Blind, where the information pertaining to the layoff came out first, which was later confirmed by the company.

However, on a deeper look, the Q3 results showed both strengths and challenges: while total revenue rose by 18% to $6.8 billion, gaming chip revenue plummeted 69% year-over-year, and embedded chip sales dropped 25%.

In its recent earnings call, AMD CEO Lisa Su underscored that the data center and AI business is now pivotal to the company’s future, expecting a 98% growth in this segment for 2024.

Su attributed the recent revenue gains to orders from clients like Microsoft and Meta, with the latter now adopting AMD’s MI300X GPUs for internal workloads.

However, unlike AMD’s relatively targeted job reductions, Intel recently implemented far larger cuts, eliminating approximately 15,000 positions amid its restructuring efforts.

AMD has been growing rapidly through initiatives such as optimizing Instinct GPUs for AI workloads and meeting data center reliability standards, which led to a $500 million increase in the company’s 2024 Instinct sales forecast.

Major clients like Microsoft and Meta too expanded their use of MI300X GPUs, with Microsoft using them for Copilot services and Meta deploying them for Llama models. Public cloud providers, including Microsoft and Oracle Cloud, along with several AI startups, also adopted MI300X instances.

This highlights AMD’s intensified focus on AI, which has driven its R&D spending up nearly 9% in the third quarter. The increased investment supports the company’s efforts to scale production of its MI325X AI chips, which are expected to be released later this year.

Besides, AMD has recently introduced its first open-source large language models under the OLMo brand, targeting a stronger foothold in the competitive AI market to compete against industry leaders like Nvidia, Intel, and Qualcomm.

“AMD could very well build a great full-stack AI proposition with a play across hardware, LLM, and broader ecosystem layers, giving it a key differentiator among other major silicon vendors, said Suseel Menon, practice director at Everest Group. AMD is considered Nvidia’s closest competitor in the high-value chip market, powering advanced data centers that handle the extensive data needs of generative AI technologies.

A Chinese company is developing a mini PC that operates inside a foldable keyboard, making it portable enough to carry in your back pocket.

A Chinese company is developing a mini PC that operates inside a foldable keyboard, making it portable enough to carry in your back pocket. The device comes from Ling Long, which debuted the foldable keyboard PC on Chinese social media. To innovate in the mini PC space, the company packed AMD's laptop chip, the Ryzen 7 8840U, inside a collapsible keyboard.

The device was designed without sacrificing any of the PC’s capabilities. The motherboard and cooling fan are built inside one half of the product, while the 16,000 mAh battery is in the other. In the center is a hinge that allows the keyboard to fold.

When folded, the keyboard is about one-fourth the size of an Apple MacBook. All the keys are normal-sized, and the keyboard features a mini touchpad near the lower-right corner.

On the downside, the product lacks a built-in display —a feature that all conventional laptops possess. But the device has a USB-A and two USB-C ports, enabling it to connect to an external monitor and any accessories. Owners can also connect the device to a monitor or tablet wirelessly. It supports Wi-Fi 6 and promises to run from 4 to 10 hours, depending on the use case.

Although no launch date was given, Ling Long plans on selling the product for 4,699 yuan ($646). In the short-term, the company is offering the foldable keyboard during a beta early access period that’ll be limited to only 200 units. The company is currently accepting orders for these test units at only 2,699 yuan for the 16GB/512GB model and 3,599 yuan for the 32GB/1TB model.

More details: https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1Dz421B7zi

On Tuesday, the US General Services Administration began an auction for the decommissioned Cheyenne supercomputer, located in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The 5.34-petaflop supercomputer ranked as the 20th most powerful in the world at the time of its installation in 2016. Bidding started at $2,500, but it's price is currently $27,643 with the reserve not yet met(More details: https://gsaauctions.gov/auctions/preview/282996).

On Tuesday, the US General Services Administration began an auction for the decommissioned Cheyenne supercomputer, located in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The 5.34-petaflop supercomputer ranked as the 20th most powerful in the world at the time of its installation in 2016. Bidding started at $2,500, but it's price is currently $27,643 with the reserve not yet met(More details: https://gsaauctions.gov/auctions/preview/282996).The supercomputer, which officially operated between January 12, 2017, and December 31, 2023, at the NCAR-Wyoming Supercomputing Center, was a powerful (and once considered energy-efficient) system that significantly advanced atmospheric and Earth system sciences research.

UCAR says that Cheynne was originally slated to be replaced after five years, but the COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted supply chains, and it clocked in two extra years in its tour of duty. The auction page says that Cheyenne recently experienced maintenance limitations due to faulty quick disconnects in its cooling system. As a result, approximately 1 percent of the compute nodes have failed, primarily due to ECC errors in the DIMMs. Given the expense and downtime associated with repairs, the decision was made to auction off the components.

With a peak performance of 5,340 teraflops (4,788 Linpack teraflops), this SGI ICE XA system was capable of performing over 3 billion calculations per second for every watt of energy consumed, making it three times more energy-efficient than its predecessor, Yellowstone. The system featured 4,032 dual-socket nodes, each with two 18-core, 2.3-GHz Intel Xeon E5-2697v4 processors, for a total of 145,152 CPU cores. It also included 313 terabytes of memory and 40 petabytes of storage. The entire system in operation consumed about 1.7 megawatts of power.

Just to compare, the world's top-rated supercomputer at the moment—Frontier at Oak Ridge National Labs in Tennessee—features a theoretical peak performance of 1,679.82 petaflops, includes 8,699,904 CPU cores, and uses 22.7 megawatts of power.

The GSA notes that potential buyers of Cheyenne should be aware that professional movers with appropriate equipment will be required to handle the heavy racks and components. The auction includes seven E-Cell pairs (14 total), each with a cooling distribution unit (CDU). Each E-Cell weighs approximately 1,500 lbs. Additionally, the auction features two air-cooled Cheyenne Management Racks, each weighing 2,500 lbs, that contain servers, switches, and power units.

For now, 12 potential buyers have bid on this computing monster so far. The auction closes on May 5 at 6:11 pm Central Time if you're interested in bidding. But don't get too excited by photos of the extensive cabling: As the auction site notes, "fiber optic and CAT5/6 cabling are excluded from the resale package."

40 Years Ago...

Jan. 22nd, 2024 12:27 pmWhen Apple announced the Macintosh personal computer with a Super Bowl XVIII television ad on January 22, 1984, it more resembled a movie premiere than a technology release. The commercial was, in fact, directed by filmmaker Ridley Scott. That’s because founder Steve Jobs knew he was not selling just computing power, storage or a desktop publishing solution. Rather, Jobs was selling a product for human beings to use, one to be taken into their homes and integrated into their lives.

This was not about computing anymore. IBM, Commodore and Tandy did computers. As a human-computer interaction scholar, I believe that the first Macintosh was about humans feeling comfortable with a new extension of themselves, not as computer hobbyists but as everyday people. All that “computer stuff” – circuits and wires and separate motherboards and monitors – were neatly packaged and hidden away within one sleek integrated box.

You weren’t supposed to dig into that box, and you didn’t need to dig into that box – not with the Macintosh. The everyday user wouldn’t think about the contents of that box any more than they thought about the stitching in their clothes. Instead, they would focus on how that box made them feel.

As computers go, was the Macintosh innovative?

Sure. But not for any particular computing breakthrough. The Macintosh was not the first computer to have a graphical user interface or employ the desktop metaphor: icons, files, folders, windows and so on. The Macintosh was not the first personal computer meant for home, office or educational use. It was not the first computer to use a mouse. It was not even the first computer from Apple to be or have any of these things. The Apple Lisa, released a year before, had them all.

It was not any one technical thing that the Macintosh did first. But the Macintosh brought together numerous advances that were about giving people an accessory – not for geeks or techno-hobbyists, but for home office moms and soccer dads and eighth grade students who used it to write documents, edit spreadsheets, make drawings and play games. The Macintosh revolutionized the personal computing industry and everything that was to follow because of its emphasis on providing a satisfying, simplified user experience.

Where computers typically had complex input sequences in the form of typed commands (Unix, MS-DOS) or multibutton mice (Xerox STAR, Commodore 64), the Macintosh used a desktop metaphor in which the computer screen presented a representation of a physical desk surface. Users could click directly on files and folders on the desktop to open them. It also had a one-button mouse that allowed users to click, double-click and drag-and-drop icons without typing commands.

The Xerox Alto had first exhibited the concept of icons, invented in David Canfield Smith’s 1975 Ph.D. dissertation. The 1981 Xerox Star and 1983 Apple Lisa had used desktop metaphors. But these systems had been slow to operate and still cumbersome in many aspects of their interaction design.

The Macintosh simplified the interaction techniques required to operate a computer and improved functioning to reasonable speeds. Complex keyboard commands and dedicated keys were replaced with point-and-click operations, pull-down menus, draggable windows and icons, and systemwide undo, cut, copy and paste. Unlike with the Lisa, the Macintosh could run only one program at a time, but this simplified the user experience.

The Macintosh also provided a user interface toolbox for application developers, enabling applications to have a standard look and feel by using common interface widgets such as buttons, menus, fonts, dialog boxes and windows. With the Macintosh, the learning curve for users was flattened, allowing people to feel proficient in short order. Computing, like clothing, was now for everyone.

Whereas prior systems prioritized technical capability, the Macintosh was intended for nonspecialist users – at work, school or in the home – to experience a kind of out-of-the-box usability that today is the hallmark of not only most Apple products but an entire industry’s worth of consumer electronics, smart devices and computers of every kind.

It is ironic that the Macintosh technology being commemorated in January 2024 was never really about technology at all. It was always about people. This is inspiration for those looking to make the next technology breakthrough, and a warning to those who would dismiss the user experience as only of secondary concern in technological innovation.

:focal(512x390:513x391)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/06/a4/06a48cbc-2c56-43cb-8ce3-0a662a0416b5/35604028241_7b653334e3_b.jpg)

Software & Hardware Development History

Jan. 10th, 2024 09:29 am Certain historic documents capture the most crucial paradigm shifts in computing technology, and they are priceless. Perhaps the most valuable takeaway from this tour of brilliance is that there is always room for new ideas and approaches.

Certain historic documents capture the most crucial paradigm shifts in computing technology, and they are priceless. Perhaps the most valuable takeaway from this tour of brilliance is that there is always room for new ideas and approaches. Right now, someone, somewhere, is working on a way of doing things that will shake up the world of software development. Maybe it's you, with a paper that could wind up being #10 on this list. Just don’t be too quick to dismiss wild ideas—including your own.

So please take a look back over the past century (nearly) of software development, encoded in papers that every developer should read:

1. Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem (1936)

Turing's writing(https://www.cs.virginia.edu/~robins/Turing_Paper_1936.pdf) has the character of a mind exploring on paper an uncertain terrain, and finding the landmarks to develop a map. What's more, this particular map has served us well for almost a hundred years.

It is a must-read on many levels, including as a continuation of Gödel's work on incompleteness(https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/goedel-incompleteness). Just the unveiling of the tape-and-machine idea makes it worthwhile.

More details: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entscheidungsproblem

2. John von Neumann: First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC (1945)

The von Neumann paper(https://web.mit.edu/STS.035/www/PDFs/edvac.pdf) asks what the character of a general computer would be, as it “applies to the physical device as well as to the arithmetical and logical arrangements which govern its functioning.” Von Neumann's answer was an outline of the modern digital computer.

3. John Backuss et al.: Specifications for the IBM Mathematical FORmula TRANSlating System, FORTRAN (1954)

The FORTRAN specification(https://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/text/Fortran/102679231.05.01.acc.pdf) gives a great sense of the moment and helped to create a model that language designers have adopted since. It captures the burgeoning sense of what was then just becoming possible with hardware and software.

4. Edsger Dijkstra: Go To Statement Considered Harmful (1968)

Aside from giving us the “considered harmful” meme, Edsger Dijkstra’s 1968 paper(https://homepages.cwi.nl/~storm/teaching/reader/Dijkstra68.pdf) not only identifies the superiority of loops and conditional control flows over the hard-to-follow go-to statement, but instigates a new way of thinking and talking about the quality of code.

Dijkstra’s short treatise also helped to usher in the generation of higher-order languages, bringing us one step closer to the programming languages we use today.

5. Diffie-Hellman: New Directions in Cryptography (1976)

When it landed, New Directions in Cryptography(https://www-ee.stanford.edu/~hellman/publications/24.pdf) set off an epic battle between open communication and government espionage agencies like the NSA. It was an extraordinary moment in software, and history in general, and we have it in writing. The authors also seemed to understand the radical nature of their proposal—after all, the paper's opening words were: “We stand today on the brink of a revolution in cryptography.”

6. Richard Stallman: The Gnu Manifesto (1985)

The Gnu Manifesto(https://www.gnu.org/gnu/manifesto.en.html) is still fresh enough today that it reads like it could have been written for a GitHub project in 2023. It is surely the most entertaining of the papers on this list.

7. Roy Fielding: Architectural Styles and the Design of Network-based Software Architectures (2000)

Fielding’s paper(https://ics.uci.edu/~fielding/pubs/dissertation/top.htm) introducing the REST architectural style landed in 2000, it summarized lessons learned in the '90’s distributed programming environment, then proposed a way forward. In this regard, I believe it holds title for two decades of software development history.

8. Satoshi Nakamoto: Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System (2008)

The now-famous Nakamoto paper(https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf) was written by a person, group of people, or entity unknown. It draws together all the prior art in digital currencies and summarizes a solution to their main problems. In particular, the Bitcoin paper addresses the double-spend problem.

Beyond the simple notion of a currency like Bitcoin, the paper suggested an engine that could leverage cryptography in producing distributed virtual machines like Ethereum.

The Bitcoin paper is a wonderful example of how to present a simple, clean solution to a seemingly bewildering mess of complexity.

9. Martin Abadi et al.: TensorFlow: A System for Large-Scale Machine Learning (2015)

This paper(https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/osdi16/osdi16-abadi.pdf) , by Martín Abadi and a host of contributors too extensive to list, focuses on the specifics of TensorFlow, especially in making a more generalized AI platform. In the process, it provides an excellent, high-level tour of the state of the art in machine learning. Great reading for the ML curious and those looking for a plain-language entry into a deeper understanding of the field.

Chocolate 3D Printing

Mar. 11th, 2023 08:43 amAll of the best 3D printers print from some form plastic, either from filament or from resin. But an upcoming printer, Cocoa Press, uses chocolate to create models you can eat. The brainchild of Maker and Battlebots Competitor Ellie Weinstein , who has been working on iterations of the printer since 2014, Cocoa Press will be available for pre-order, starting on April 17th via cocoapress.com (the company is also named Cocoa Press).

Cocoa Press DIY kits will start at $1,499 and are estimated to ship in September while professional packages, which come fully built, will cost $3,995 and ship in early 2024. When reserving your printer, you'll only have to put $100 deposit down with the rest due at shipping time. The company says that it should take 10 hours to put together the DIY kit.

The Cocoa Press has a build volume of 140 x 150 x 150 mm, which is small for a regular 3D printer, but more than adequate for most chocolate creations. Unlike most plastic filaments that need to be heated to at 200 to 250 degrees Celsius, this printer only heats its chocolate up to 33 degrees Celsius (91.4 degrees Fahrenheit), which is just short of body temperature. The bed is not heated.

In lieu of a roll of filament or a tank full of resin, the Cocoa Press uses 70g cartridges of special chocolate that solidifies at up to 26.67 degrees Celsius (80 degrees Fahrenheit), which the company will sell for $49 for a 10 pack. The cigar-shaped chocolate pieces go into a metal syringe where the entire thing is melted at the same time rather than melting as it passes through the extruder (like a typical FDM printer).

The printer is safe and sanitary as the chocolate only touches four parts, which are all easy to remove (without tools) and clean in a sink. The Cocoa Press has an attractive orange, silver and black aesthetic that's reminiscent of a Prusa Mini+.

It uses an Ultimachine Archim2 32-bit processor that's powered by Marlin firmware, the same type which comes on most FDM printers. You can use standard 3D models that you create or download from sites like Printables or Thingiverse and then slice them in PrusaSlicer.

This is not the very first printer that Cocoa Press has released. Weinstein's company sold a larger and much more expensive model, technically known as version 5 "Chef," for $9,995 back in 2020, but she stopped producing that and is now focusing on the less expensive, smaller model. She told us that everyone who bought the old model will receive a free copy of the new one.

Terms that are beginning to emerge, such as “supercloud,” “distributed cloud,” “metacloud”, and “abstract cloud.” Even the term “cloud native” is up for debate. The common pattern seems to be a collection of public clouds and sometimes edge-based systems that work together for some greater purpose.

Terms that are beginning to emerge, such as “supercloud,” “distributed cloud,” “metacloud”, and “abstract cloud.” Even the term “cloud native” is up for debate. The common pattern seems to be a collection of public clouds and sometimes edge-based systems that work together for some greater purpose.The metacloud concept will be the single focus for the next 5 to 10 years as we begin to put public clouds to work. Having a collection of cloud services managed with abstraction and automation is much more valuable than attempting to leverage each public cloud provider on its terms rather than yours.

We want to leverage public cloud providers through abstract interfaces to access specific services, such as storage, compute, artificial intelligence, data, etc., and we want to support a layer of cloud-spanning technology that allows us to use those services more effectively. A metacloud removes the complexity that multicloud brings these days. Also, scaling operations to support multicloud would not be cost-effective without this cross-cloud layer of technology.

Thus, we’ll only have a single layer of security, governance, operations, and even application development and deployment. This is really what a multicloud should become. If we attempt to build more silos using proprietary tools that only work within a single cloud, we’ll need many of them. We’re just building more complexity that will end up making multicloud more of a liability than an asset.

I really don’t care what we call it and however, this does not change the fact that metacloud is perhaps the most important architectural evolution occurring right now, and we need to get this right out of the gate. If we do that, who cares what it is named.

Raspberry Pi

Oct. 23rd, 2021 10:39 am

While social distancing might have become less of a priority for many as 2021 has drawn to a close, this DIY project helps bring the distant members of your household (including kids or spouses working from home) a little closer. It started as an effort to keep a quarantined-for-weeks father in touch with his daughter in the same house.

Thanks to the creative use of a Telegram voice-chat bot, you can use Raspberry Pi to call family members to dinner or let them know that Daddy or Mommy (hopefully, not both at once) is leaving the house for a mental health day. All that is needed here is a Raspberry Pi board, a USB microphone, a USB speaker, a few buttons, and a willingness not to shout at family members who don’t respond immediately.

Another ingenious way that Raspberry Pi has been tweaked to help individuals and communities during the pandemic: How about as a COVID cop? By using facial landmarking software and infrared temperature sensors, this Pi project makes for an affordable, touch-free kiosk that provides contactless temperature checks and confirms that each person that passes is wearing a mask.

Because fever is the leading symptom of COVID-19, temperature checkpoints have been staples in some schools, offices, and other workplaces. It's not always possible, though, to manually check temperatures using a contactless thermometer (you need the personnel to do that), and they place the person testing temperatures at risk of exposure.

To solve these problems, 19-year-old designed a kiosk that automates the process of temperature checks by using facial landmarking, deep-learning tech, and an IR temperature sensor. Behold, above, the TouchFree v2: Contactless Temperature and Mask Checkup. His model was made with a Raspberry Pi 3 Model B, a Pi Touch display, a Pi Camera Module, and several other bits, supplemented by a 3D printed structure. The Raspbian variant serves as the OS.

Although this project seems simple, it’s a fantastic way for beginners to work on basic logic, or for more advanced makers to show off their skills. Using LEDs to go from simple patterns to complex transitions, you can create a stunning visual-accent piece for your home.

Although this project seems simple, it’s a fantastic way for beginners to work on basic logic, or for more advanced makers to show off their skills. Using LEDs to go from simple patterns to complex transitions, you can create a stunning visual-accent piece for your home.Add a microphone, and you can even program the LEDs to alter their color or pattern based on sounds, reacting to voices or music in your home. The LumiCube project shown above is projected to be available as a kit in 2022 via an Indiegogo push (preceded by a Kickstarter) that was running at this writing. (In this design, you would bring your own Pi to the kit.) The "project source" link further up showcases the build and programming behind it.

One of the most popular uses for Raspberry Pi hardware is to breathe new life into older technology that would have otherwise joined a landfill. Take that dead old Apple laptop out of your closet or grab that '90s-era IBM ThinkPad from your parents’ attic, and use any of them as a housing for a Raspberry Pi!

Older laptops are ideal for this project, as their chassis' larger internal volume provides enough space for the hardware you need. Most of the Pi hardware can be placed under the keyboard after gutting the original internals. In the example project above, the user hollowed out an older MacBook laptop and showed off the project at this Reddit thread(https://www.reddit.com/r/raspberry_pi/comments/n4xzd0/macbook_pi_from_an_old_a1181_and_rpi4).

Mind you, none of this will be easy. The original onboard batteries may need to be replaced or modified to power both the Raspberry Pi and the display, with careful selection of a voltage regulator or switching power supply to ensure the Raspberry Pi sees just 5 volts of input. Also note that external controllers will be needed to get the laptop screen acting as the Pi display. (Assuming that that part of the laptop still works!) Not one for the faint of heart or hardware.

Many resourceful gamers have created retro-gaming consoles using emulation software running on Raspberry Pi. The newest variation on this theme is creating mobile game consoles the same size as the original Nintendo Game Boy, or fitting an entire retro gaming console inside a single SNES game cartridge. How's that for a dramatic meta-illustration of how far things have come in video gaming?

Many resourceful gamers have created retro-gaming consoles using emulation software running on Raspberry Pi. The newest variation on this theme is creating mobile game consoles the same size as the original Nintendo Game Boy, or fitting an entire retro gaming console inside a single SNES game cartridge. How's that for a dramatic meta-illustration of how far things have come in video gaming?he SNES:Pi Zero runs the RetroPie operating system. RetroPie can emulate thousands of games. (Of course, you need to download the game ROMs separately.) The Raspberry Pi Zero W at the heart of the SNES cartridge can run the majority of console games released prior to the N64. Hardware inside comprises a USB hub, the Pi Zero, and a micro SD card. You will, of course, also need an external display or TV.

Stop wasting time installing ad blockers on every device and every web browser in your home and use the power of Raspberry Pi to block ads across your entire home network. The Pi-hole is a DNS-based filtering tool that runs on the super-cheap Raspberry Pi Zero and blocks ads before any other device on your Wi-Fi network gets involved.

If you’re concerned about blocking ads that you need to see (maybe your boss wants you to confirm that ads are working on the company website) you can also whitelist specific URLs so those ads remain untouched.

You want to block door-to-door salespeople or other solicitors. Or maybe the pandemic has left you unready to deal with actual humans at your front door quite yet. Then try a Raspberry Pi-based smart doorbell with video intercom. For this project, you’ll need an LCD screen, a call button, a speaker, a microphone, and a camera so you can video chat with people at your front door. (It can also be implemented as a room-to-room intercom.)

With this project, you can implement a simple script to send a Gmail notification to your phone whenever someone presses the doorbell/intercom button. From there, the Raspberry Pi can use a free video conferencing service like Jitsi Meet to enable a live video chat. The bits include a Pi 3 Model B; LCD, camera, and mic components; and a host of internal connectors.

No one appreciates having their Amazon deliveries stolen from their front porch. You can find a variety of cheap alarms online that use motion detectors, but then you have an alarm that goes off every time someone approaches your front door.

his porch pirate alarm project uses Raspberry Pi and artificial intelligence to identify when packages have been delivered and then sounds an alarm only when a package has been removed. You can even set up the camera to send you footage of the thief so you can provide that evidence to local authorities. The model demonstrated here is built off of a Raspberry Pi 4 and a Wyse video camera.

Why use a boring Amazon Echo with Alexa or a Google Home device when you can use Raspberry Pi to bring HAL 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey to life? Hal won’t be a fictional artificial intelligence after you’ve finished this project.

Okay, the guts may be a bit less impressive than the film may suggest they should be: At its core, this Raspberry Pi HAL 9000 is just a humble Pi Model 3 or 4, a speaker, a USB microphone, and a red LED with some creative window dressing. The maker here also has the HAL-alike serving as a NAS. Just remember to run if HAL starts singing “Daisy Bell.”

Why should we hominids be the only ones to benefit from cheap DIY tech? You can use the power of Raspberry Pi, a button, and a simple motor to build a dog treat dispenser so humanity's best friend can reap the rewards of artificial intelligence. (Granted, the pegboard-mounted design is a bit rustic.)

Why should we hominids be the only ones to benefit from cheap DIY tech? You can use the power of Raspberry Pi, a button, and a simple motor to build a dog treat dispenser so humanity's best friend can reap the rewards of artificial intelligence. (Granted, the pegboard-mounted design is a bit rustic.)Of course, the only thing better than pressing a button to deliver dog treats is to have it happen automatically. This Reddit user set up his Raspberry Pi as a web scraper to detect when his Instagram account gets a new follower. The follower addition then triggers the motor, which, in turn, activates the treat dispenser.

Yes, before you ask: Of course Ring cameras already exist. Those and other cheap security cameras are a great way to keep an eye on your home, but now you can use Raspberry Pi and some creativity to identify family and friends, and send you an alert to let you know if, say, a buddy or your mother-in-law drops by when you’re away, but doesn't leave a note.

The basic setup consists of a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B, a micro SD card, a camera with enclosure, and a power supply. Once you’ve set up the camera, you can send the footage to another client device or send it straight to your phone. With some additional programming, you can use facial recognition to identify specific people and have the Pi send you an alert when an unknown person visits your home.

Get rid of that boring old mirror in your living room and replace it with a modern version of the mythical magic mirror! A smart mirror displays web-based applications that let you check local news, the weather, your daily calendar, and more while you preen, pluck, shave, apply makeup, or dress. The Pi comes into play as the compute source and the driver of the built-in video.

This project involves some basic carpentry (for the mirror frame) and benefits from a 3D printer for some of the framework, but you can keep it simpler: You can use an old LED desktop monitor, an acrylic see-through mirror, and a Raspberry Pi as the basis for your own smart mirror.

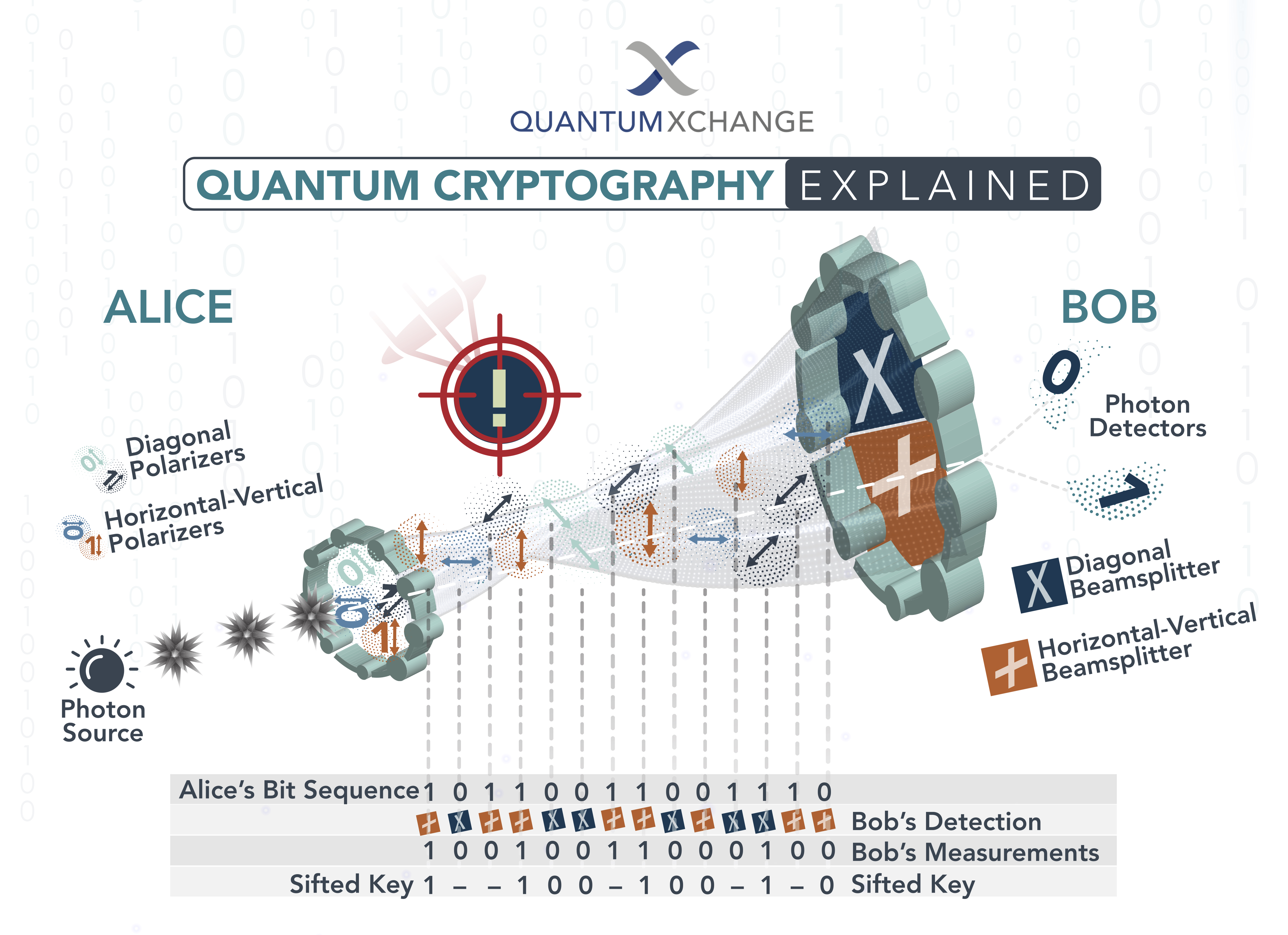

The U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) has issued a FAQ(https://media.defense.gov/2021/Aug/04/2002821837/-1/-1/1/Quantum_FAQs_20210804.PDF) titled "Quantum Computing and Post-Quantum Cryptography FAQs" where the agency explores the potential implications for national security following the likely arrival of a "brave new world" beyond the classical computing sphere. As the race for quantum computing accelerates, with a myriad of players attempting to achieve quantum supremacy through various, exotic scientific investigation routes, the NSA document explores the potential security concerns arising from the prospective creation of a “Cryptographically Relevant Quantum Computer” (CRQC).

The U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) has issued a FAQ(https://media.defense.gov/2021/Aug/04/2002821837/-1/-1/1/Quantum_FAQs_20210804.PDF) titled "Quantum Computing and Post-Quantum Cryptography FAQs" where the agency explores the potential implications for national security following the likely arrival of a "brave new world" beyond the classical computing sphere. As the race for quantum computing accelerates, with a myriad of players attempting to achieve quantum supremacy through various, exotic scientific investigation routes, the NSA document explores the potential security concerns arising from the prospective creation of a “Cryptographically Relevant Quantum Computer” (CRQC).A CRQC is the advent of a quantum-based supercomputer that is powerful enough to break current, classical-computing-designed encryption schemes. While these schemes (think AES-256, more common on the consumer side, or RSA 3072-bit or larger for asymmetrical encryption algorithms) are virtually impossible to crack with current or even future supercomputers, a quantum computer doesn't play by the same rules due to the nature of the beast and the superposition states available to its computing unit, the qubit.

With the race for quantum computing featuring major private and state players, it's not just the expected $26 billion value of the quantum computing sphere by 2030 that worries security experts - but the possibility of quantum systems falling into the hands of rogue entities. We need only look to the history of hacks in the blockchain sphere to see that where there is an economic incentive, there are hacks - and data is expected to become the number one economic source in a (perhaps not so) distant future.

Naturally, an entity such as the NSA, which ensures the safety of the U.S.'s technological infrastructure, has to not only deal with present threats, but also future ones - as one might imagine, it takes an inordinate amount of time for entities as grand as an entire country's critical government systems to be updated.

According to the NSA, "New cryptography can take 20 years or more to be fully deployed to all National Security Systems (NSS)". And as the agency writes in its document, "(...) a CRQC would be capable of undermining the widely deployed public key algorithms used for asymmetric key exchanges and digital signatures. National Security Systems (NSS) — systems that carry classified or otherwise sensitive military or intelligence information — use public key cryptography as a critical component to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity of national security information. Without effective mitigation, the impact of adversarial use of a quantum computer could be devastating to NSS and our nation, especially in cases where such information needs to be protected for many decades."

The agency's interest in quantum computing is such, even, that as a part of the document trove leaked by Edward Snowden(https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/nsa-seeks-to-build-quantum-computer-that-could-crack-most-types-of-encryption/2014/01/02/8fff297e-7195-11e3-8def-a33011492df2_story.html?hpid=z1), it was revealed that the agency invested $79.7 million in a research program titled “Penetrating Hard Targets” - which aimed to explore whether a quantum computer for actually breaking traditional encryption protocols was feasible to pursue at the time.

This is especially important considering that an algorithm that can be employed by a quantum computer to break traditional encryption schemes already exists in the form of Schor's algorithm, first demonstrated in 1994 - before humanity's control over the qubit was all but a distant dream. The only thing standing in the way of the Schor algorithm's implementation at a quantum level is that it requires a much larger amount of qubits than is currently feasible - orders of magnitude higher than today's most advanced quantum computing designs, that max out at around "only" one hundred qubits.

It is only a matter of time, however, before such systems exist. The answer lies in the creation and deployment of so-called post-quantum cryptography - encryption schemes designed to give pause to or even completely thwart future CRQCs. These already exist. However, their deployment at a time where the cryptographic security threat of quantum computing still lays beyond the horizon, implementing post-quantum cryptography would present issues in terms of infrastructure interoperability - different systems from different agencies and branches sharing confidential information between themselves and understanding what they're transmitting between each other.

In its documentation, NSA puts the choice on exactly what post-quantum cryptography will be implemented by the U.S. national infrastructure on the feet of the National Institute of Standards and Technologies (NIST), which is "in the process of standardizing quantum-resistant public key in their Post-Quantum Standardization Effort, which started in 2016. This multi-year effort is analyzing a large variety of confidentiality and authentication algorithms for inclusion in future standards," the NSA writes.

But contrary to what some would have you think, the NSA knows that it's a matter of time before quantum computing turns the security world on its proverbial head. There's no stopping the march of progress; as the agency writes, "The intention is to (...) remove quantum-vulnerable algorithms and replace them with a subset of the quantum-resistant algorithms selected by NIST at the end of the third round of the NIST post-quantum effort."

Quantum is coming; Post-quantum security must come before it.

40 Years Ago

Aug. 12th, 2021 12:17 pm

On August 12, 1981, IBM introduced the IBM Personal Computer: https://www.pcmag.com/news/project-chess-the-story-behind-the-original-ibm-pc

List of innovative IBM machines from the first decade of the PC, 1981-1990: https://www.pcmag.com/news/the-golden-age-of-ibm-pcs

IBM Press Release: https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/pc25/pc25_press.html

Most PCs tend to boot from a primary media storage, be it a hard disk drive, or a solid-state drive, perhaps from a network, or – if all else fails – the USB stick or the boot DVD comes to the rescue… Fun, eh? Boring! Why don’t we try to boot from a record player for a change?

So this nutty little experiment connects a PC, or an IBM PC(Details: http://boginjr.com/electronics/old/ibm5150) to be exact, directly onto a record player through an amplifier. There is a small ROM boot loader that operates the built-in “cassette interface” of the PC (that was hardly ever used), invoked by the BIOS if all the other boot options fail, i.e. floppy disk and the hard drive. The turntable spins an analog recording of a small bootable read-only RAM drive, which is 64K in size. This contains a FreeDOS kernel, modified to cram it into the memory constraint, a micro variant of COMMAND.COM and a patched version of INTERLNK, that allows file transfer through a printer cable, modified to be runnable on FreeDOS. The bootloader reads the disk image from the audio recording through the cassette modem, loads it to memory and boots the system on it.

And now to get more technical: this is basically a merge between BootLPT/86(Details: http://boginjr.com/it/sw/dev/bootlpt-86) and 5150CAXX(Details: http://boginjr.com/it/sw/dev/5150caxx), minus the printer port support. It also resides in a ROM, in the BIOS expansion socket, but it does not have to. The connecting cable between the PC and the record player amplifier is the same as with 5150CAXX, just without the line-in (PC data out) jack.

The “cassette interface” itself is just PC speaker timer channel 2 for the output, and 8255A-5 PPI port C channel 4 (PC4, I/O port 62h bit 4) for the input. BIOS INT 15h routines are used for software (de)modulation.

The boot image is the same 64K BOOTDISK.IMG “example” RAM drive that can be downloaded at the bottom of the BootLPT article. This has been turned into an “IBM cassette tape”-protocol compliant audio signal using 5150CAXX, and sent straight to a record cutting lathe.

Vinyls are cut with an RIAA equalization curve that a preamp usually reverses during playback, but not perfectly. So some signal correction had to be applied from the amplifier and make it work right with the line output straight from the phono preamp. In this case, involving a vintage Harman&Kardon 6300 amplifier with an integrated MM phono preamp, you had to fade the treble all the way down to -10dB/10kHz, increase bass equalization to approx. +6dB/50Hz and reduce the volume level to approximately 0.7 volts peak, so it doesn’t distort. All this, naturally, with any phase and loudness correction turned off.

Of course, the cassette modem does not give a hoot in hell about where the signal is coming from. Notwithstanding, the recording needs to be pristine and contain no pops or loud crackles (vinyl) or modulation/frequency drop-outs (tape) that will break the data stream from continuing. However, some wow is tolerated, and the speed can be 2 or 3 percent higher or lower too.

For those interested, the bootloader binary designed for a 2364 chip (2764s can be used, through an adaptor), can be obtained here: http://boginjr.com/apps/vinyl-boot/BootVinyl.bin

It assumes an IBM 5150 with a monochrome screen and at least 512K of RAM. The boot disk image can be obtained at the bottom of the BootLPT/86 article, and here’s its analog variant: http://boginjr.com/misc/bootdisk.flac

Z4 considered the oldest preserved digital computer in the world and one of those machines that takes up a whole room, runs on magnetic tapes, and needs multiple people to operate. Today it sits in the Deutsches Museum in Munich, unused. Until now, historians and curators only had a limited knowledge of its secrets because the manual was lost long ago.

Z4 considered the oldest preserved digital computer in the world and one of those machines that takes up a whole room, runs on magnetic tapes, and needs multiple people to operate. Today it sits in the Deutsches Museum in Munich, unused. Until now, historians and curators only had a limited knowledge of its secrets because the manual was lost long ago.The computer’s inventor, Konrad Zuse, first began building it for the Nazis in 1942, then refused its use in the VI and V2 rocket program. Instead, he fled to a small town in Bavaria and stowed the computer in a barn until the end of the war. It wouldn’t see operation until 1950. The Z4 proved to be a very reliable and impressive computer for its time. With its large instruction set it was able to calculate complicated scientific programs and was able to work during the night without supervision, which was unheard of for this time.

These qualities made the Zuse Z4 particularly useful to the Institute of Applied Mathematics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), where the computer performed advanced calculations for Swiss engineers in the early 50s. Around 100 jobs were carried out with the Z4 between 1950 and 1955. These included calculations on the trajectory of rockets… on aircraft wings… and on flutter vibrations, an operation requiring 800 hours machine time.

René Boesch, one of the airplane researchers working on the Z4 in the 50s kept a copy of the manual among his papers, and it was there that his daughter, Evelyn Boesch, also an ETH researcher, discovered it. View it online here: https://www.e-manuscripta.ch/zut/content/pageview/2856521

The full story of the computer’s development, operation, and the rediscovery of its only known copy of operating instructions you can view here: https://cacm.acm.org/blogs/blog-cacm/247521-discovery-user-manual-of-the-oldest-surviving-computer-in-the-world/fulltext