Every three days Nathan, a 27-year-old venture capitalist in San Francisco, ingests 15 micrograms of lysergic acid diethylamide (commonly known as lsd or acid). The microdose of the psychedelic drug – which generally requires at least 100 micrograms to cause a high – gives him the gentlest of buzzes. It makes him feel far more productive, he says, but nobody else in the office knows that he is doing it. “I view it as my little treat. My secret vitamin,” he says. “It’s like taking spinach and you’re Popeye.”

Nathan first started microdosing in 2014, when he was working for a startup in Silicon Valley. He would cut up a tab of lsd into small slices and place one of these on his tongue each time he dropped. His job involved pitching to investors. “So much of fundraising is storytelling, being persuasive, having enough conviction. Microdosing is pretty fantastic for being a volume knob for that, for amplifying that.” He partly credits the angel investment he secured during this period to his successful experiment in self-medication.

Of all the drugs available, psychedelics have long been considered among the most powerful and dangerous. When Richard Nixon launched the “war on drugs” in the 1970s, the authorities claimed lsd caused people to jump out of windows and fried users’ brains. When Ronald Reagan was the governor of California, which in 1966 was one of the first states to criminalise the drug, he argued that “anyone that would engage or indulge in [lsd] is just a plain fool”.

Yet attitudes towards psychedelics appear to be changing. According to a 2013 paper from two Norwegian researchers that used data from 2010, Americans aged between 30 and 34 – not the original flower children but the next generation – were the most likely to have tried lsd. An ongoing survey of middle-school and high-school students shows that drug use has fallen across the board among the young (as in most of the rich world). Yet, lsd use has recently risen a little, and the perceived risks of the drug fallen, among 13- to 17-year-olds.

As with many social changes, from transportation to food delivery to dating, Silicon Valley has blazed a trail with microdosing. It may yet influence the way that America, and eventually the West, view psychedelic substances.

Lsd’s effects were discovered by accident. In April 1943 Albert Hoffmann, a Swiss scientist, mistakenly ingested a small amount of the chemical, which he had synthesised a few years earlier though never tested. Three days later he took 250 micrograms of the drug on purpose and had a thoroughly bad trip, but woke up the next day with a “sensation of well-being and renewed life”. Over the next decade, lsd was used recreationally by a select group of people, such as the writer Aldous Huxley. But not until it was mass produced in San Francisco in the 1960s did it fill the sails of the hippy movement and inspire the catchphrase “turn on, tune in and drop out”.

From the start, a small but significant crossover existed between those who were experimenting with drugs and the burgeoning tech community in San Francisco. “There were a group of engineers who believed there was a causal connection between creativity and lsd,” recalls John Markoff, whose 2005 book, “What the Dormouse Said”, traces the development of the personal-computer industry through 1960s counterculture. At one research centre in Menlo Park over 350 people – particularly scientists, engineers and architects – took part in experiments with psychedelics to see how the drugs affected their work. Tim Scully, a mathematician who, with the chemist Nick Sand, produced 3.6m tabs of lsd in the 1960s, worked at a computer company after being released from his ten-year prison sentence for supplying drugs. “Working in tech, it was more of a plus than a minus that I worked with lsd,” he says. No one would turn up to work stoned or high but “people in technology, a lot of them, understood that psychedelics are an extremely good way of teaching you how to think outside the box.”

San Francisco appears to be at the epicentre of the new trend, just as it was during the original craze five decades ago. Tim Ferriss, an angel investor and author, claimed in 2015 in an interview with cnn that “the billionaires I know, almost without exception, use hallucinogens on a regular basis.” Few billionaires are as open about their usage as Ferriss suggests. Steve Jobs was an exception: he spoke frequently about how “taking lsd was a profound experience, one of the most important things in my life”. In Walter Isaacson’s 2011 biography, the Apple ceo is quoted as joking that Microsoft would be a more original company if Bill Gates, its founder, had experienced psychedelics.

As Silicon Valley is a place full of people whose most fervent desire is to be Steve Jobs, individuals are gradually opening up about their usage – or talking about trying lsd for the first time. According to Chris Kantrowitz, the ceo of Gobbler, a cloud-storage company, and the head of a new fund investing in psychedelic research, people were refusing to talk about psychedelics as recently as three years ago. “It was very hush hush, even if they did it.” Now, in some circles, it seems hard to find someone who has never tried it.

Lsd works by interacting with serotonin, the chemical in the brain that modulates mood, dreaming and consciousness. Once the drug enters the brain (no mean feat), it hijacks the serotonin 2a receptor, explains Robin Carhart-Harris, a scientist at Imperial College London who is among those mapping out the effects of psychedelics using brain-scanning technology. The 2a receptor is most heavily expressed in the cortex, the part of the brain in which consciousness could be said to reside. One of the first effects of psychedelics such as lsd is to “dissolve a sense of self,” says Carhart-Harris. This is why those who have taken the drug sometimes describe the experience as mystical or spiritual.

The drug also seems to connect previously isolated parts of the brain. Scans from Carhart-Harris’s research, conducted with the Beckley Foundation in Oxford, show a riot of colour in the volunteers’ brains, compared with those who have taken a placebo. The volunteers who had taken lsd did not just process those images they had actually seen in their visual cortexes; instead many other parts of the brain started processing visions, as though the subject was seeing things with their eyes shut. “The brain becomes more globally interconnected,” says Carhart-Harris. The drug, by acting on the serotonin receptor, seems to increase the excitability of the cortex; the result is that the brain becomes far “more open”.

In an intensely competitive culture such as Silicon Valley, where everyone is striving to be as creative as possible, the ability for lsd to open up minds is particularly attractive. People are looking to “body hack”, says Kantrowitz: “How do we become better humans, how do we change the world?” One ceo of a small startup describes how, on an away-day with his company, everyone took magic mushrooms. It allowed them to “drop the barriers that would typically exist in an office”, have “heart to hearts”, and helped build the “culture” of the company. (He denied himself the pleasure of partaking so that he could make sure everyone else had a good time.) Eric Weinstein, the managing director of Thiel Capital, told Rolling Stone magazine last year that he wants to try and get as many people to talk openly about how they “directed their own intellectual evolution with the use of psychedelics as self-hacking tools”.

Young developers and engineers, most of them male, seem to be particularly keen on his form of bio-hacking. Alex (also not his real name), a 27-year-old data scientist who takes acid four or five times a year, feels psychedelics give him a “wider perspective” on his life. Drugs are a way to take a break, he says, particularly in a culture where people are “super hyper focused” on their work. A typical pursuit among many millennial workers, along with going to drug-fuelled music festivals or the annual Burning Man festival in the Nevada desert, is for a group of friends to rent a place in the countryside, take lsd or magic mushrooms and go for a hike (some call it a “hike-a-delic”). “I would be much more wary of telling co-workers I had done coke the night before than saying I had done acid on the weekend,” says Mike (yet another pseudonym), a 25-year-old researcher at the University of California in San Francisco, who also takes lsd regularly. It is seen as something “worthwhile, wholesome, like yoga or wholegrain”.

The quest for spiritual enlightenment – as with much else in San Francisco – is fuelled by the desire to increase productivity. Microdosing is one such product of this calculus. Interest in the topic first started to take off around 2011, when Jim Fadiman, a psychologist who took part in the experiments in Menlo Park in the 1960s, published a book on psychedelics and launched a website on the topic. “Microdosing is popular among the technologically aware, physically healthy set,” says Fadiman. “Because they are interested in science, nutrition and their own brain chemistry.” Microdoses, he claims, can also decrease social awkwardness. “I meet a lot of these people. They are not the most adept social class in the world.” Paul Austin has also written a book on microdosing and lectures on the subject across Europe and America. Many of the people he speaks to are engineers, business owners, writers and “digital nomads” looking for ways to outrun automation in the “new economy”. Drugs that “make you think differently” are one route to survival, he says.

Although data on the number of people microdosing are non-existent, since drug surveys do not ask about it, a group on Reddit now has 16,000 members, up from a couple of thousand a year ago. People post about their experiences, and most of them follow Fadiman’s suggestion of taking up to ten micrograms every three days or so. “My math is slightly better, I swear. Or maybe it’s just my confidence, either way, I am more aware, creative and have amazing ideas,” says one user, answering an inquiry about whether there is correlation between intelligence and microdosing. “I feel less adhd, greater focus,” says another user. He can identify “no bad habits [except] maybe I speak my mind more and offend people because I am very smart and often put people down with condescending remarks by accident.”

Microdosing is the logical conclusion of several trends, thinks Rick Doblin, the founder of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, a research and lobby group. For a start, many of those who took acid in the 1960s are still around, having turned into well-preserved baby-boomers. “Now, at the end of their lives, they can say that these drugs were valuable. They are not all on a commune, growing soybeans, dropping out,” he says.

Another reason for the trend is that, although there have been no scientific studies on microdosing, research on psychedelics has suggested that they may, in certain settings, have therapeutic uses. The increasing use of marijuana for medical use, and its legalisation in many states, has also led to people looking at drugs more favourably. “There’s no longer this intense fervour about drugs being dreadful,” says Doblin. Last year a study of 51 terminally ill cancer patients carried out by scientists at Johns Hopkins University appeared to suggest that a single, large dose of psilocybin – another psychedelic and the active ingredient in magic mushrooms – reduced anxiety and depression in most participants. This helps encourage those who may normally be wary of taking drugs to experiment with them, or to take them in lower, less terrifying doses. Ayelet Waldman, a writer who microdosed for a month on lsd and wrote a book documenting her experiences, makes much of the fact she is a mother, a professional and used to work with drug offenders. She is not your typical felon. (Indeed, she gave up the drug after that month, in order to stop breaking the law. But “there is no doubt in my mind that if it were legal I would be doing it,” she says.)

The availability of legal substitutes for lsd in certain parts of the world has also made microdosing far easier. Erica Avey, who works for Clue, a Berlin-based app which tracks women’s menstrual cycles, started microdosing in April with 1p-lsd, a related drug, which is still legal in Germany. Although she took it to balance her moods, she quickly found that it also helped her with her work. It made her “sharper, more aware of what my body needs and what I need,” she says. She now gets to work earlier in the morning, at 8am, when she is most productive, and leaves in the afternoon when she has a slump in energy. “At work I am more socially present. You are not really caught up in the past and the future. For meetings it’s great,” she enthuses.

Lsd is not thought to be addictive. Although people who use it regularly build up a tolerance, there is not the same “reward” that users of heroin and alcohol, two deeply addictive drugs, seek through increasing their dosages. “They are not moreish drugs,” says Carhart-Harris. The buzz of psychedelics is more abstract than other drugs, such as cocaine, which tend to make people feel good about themselves. Those who have good experiences with hallucinogens report an enhanced connection to the world (they take up veganism; they feel more warmly towards their families). Most people who microdose insist that, although they make a habit of taking it, they do not feel dependent. “With coffee you need a cup to feel normal,” says Avey. “I would never need lsd to feel normal.” She may quit later this year, having reaped enough beneficial effects. Many talk of a sense in which the dose, even though it is almost imperceptibly small, seems to stay with them. Often they feel best on the second or third day after ingestion. “I’ve definitely experienced the same levels of creativity without taking it...you retain it,” says Nathan.

The effects of microdosing depend on the environment and the work one is doing. It will not automatically improve matters. Since moving to an office with less natural light, Nathan has not found lsd as effective, although he still takes it every three days or so. Similarly, Avey doubts it would be as useful if she did not have a job she liked and a “cool work environment” (with an in-house therapist and yoga classes). Carhart-Harris raises the potential issue of “containment”. Whereas beneficial effects of psychedelics can be seen in therapeutic environments, the spaces in which people microdose are much more diverse. A crowded subway car or an irritating meeting can become more unbearable; not every effect will be a positive one.

Currently the lack of medical research on microdosing means that it has been touted as a panacea for everything from depression and menstrual pain to migraines and impotence. The only problem that people do not try to solve through microdosing is anxiety. Since these drugs tend to heighten people’s perceptions, they are likely to exacerbate anxiety. Without more research, it is hard to know whether such a small amount of a psychedelic works merely as a placebo, and whether there are any long-term detrimental consequences, such as addiction.

There is still an understandable fear of lsd, and it is unlikely to migrate from Silicon Valley to America’s more conservative regions anytime soon. But in a country which is awash with drugs, microdosing with an illicit substance may not seem so outlandish, particularly among the middle-classes. Already many Americans are happy to medicalise productivity. In 2011 3.5m children were prescribed drugs to treat attention disorders, up from 2.5m in 2003, and these drugs are widely used off prescription to enhance performance at work. By one estimate, 12% of the population takes an antidepressant. Americans also try to eliminate pain, mental or otherwise, by other means; the opioid epidemic has partly been caused by massive over-prescription of painkillers. Compared with these, lsd – which is almost impossible to overdose on – may no longer seem so threatening. It may help people tune in, but it no longer has the reputation of making them drop out.

Friday afternoon in San Francisco: On one side of Mission Street, hotel workers chanted and banged on a drum outside the Marriott Marquis, part of a monthslong strike for higher wages and more jobs. On the other, a tech company’s billboard proclaimed, “Stop hiring humans.”

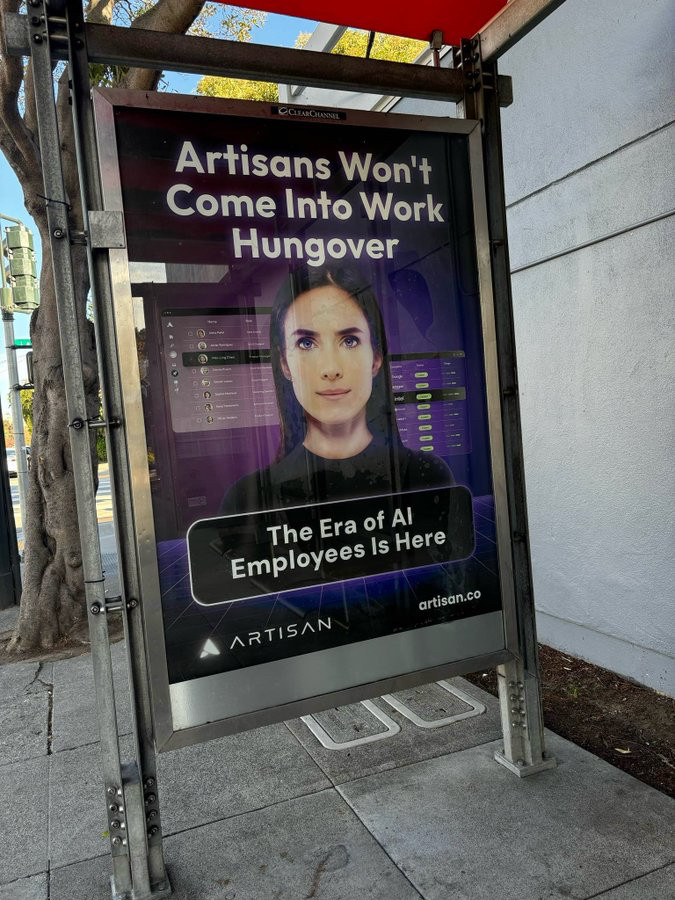

Friday afternoon in San Francisco: On one side of Mission Street, hotel workers chanted and banged on a drum outside the Marriott Marquis, part of a monthslong strike for higher wages and more jobs. On the other, a tech company’s billboard proclaimed, “Stop hiring humans.” But the billboards in San Francisco are less routine. Bleak might be a better word, or mean-spirited. And in a city laden with jargony advertisements, these are easy to understand. Most feature a dark-haired, purple-eyed persona and a few rows of text. Some critique humans and remote work: “Artisans won’t complain about work-life balance” and “Artisan’s Zoom cameras will never ‘not be working’ today.” Others are more direct: “Hire Artisans, not humans.” Several include the line, “The era of AI employees is here.”

But the billboards in San Francisco are less routine. Bleak might be a better word, or mean-spirited. And in a city laden with jargony advertisements, these are easy to understand. Most feature a dark-haired, purple-eyed persona and a few rows of text. Some critique humans and remote work: “Artisans won’t complain about work-life balance” and “Artisan’s Zoom cameras will never ‘not be working’ today.” Others are more direct: “Hire Artisans, not humans.” Several include the line, “The era of AI employees is here.” If you asked how Artisan CEO Jaspar Carmichael-Jack responds to critiques of the billboards. He acknowledged the ads’ “dystopian” tone but stood by it.

If you asked how Artisan CEO Jaspar Carmichael-Jack responds to critiques of the billboards. He acknowledged the ads’ “dystopian” tone but stood by it.

Yesterday, over Silicon Valley, the world is getting its first look at Pathfinder 1, a prototype electric airship that its maker LTA Research hopes will kickstart a new era in climate-friendly air travel, and accelerate the humanitarian work of its funder, Google co-founder Sergey Brin.

Yesterday, over Silicon Valley, the world is getting its first look at Pathfinder 1, a prototype electric airship that its maker LTA Research hopes will kickstart a new era in climate-friendly air travel, and accelerate the humanitarian work of its funder, Google co-founder Sergey Brin.

As autonomous vehicles become increasingly popular in San Francisco, some riders are wondering just how far they can push the vehicles’ limits—especially with no front-seat driver or chaperone to discourage them from questionable behavior.

As autonomous vehicles become increasingly popular in San Francisco, some riders are wondering just how far they can push the vehicles’ limits—especially with no front-seat driver or chaperone to discourage them from questionable behavior.

Tucked away near the easternmost edge of the city of Atherton is a block of two dozen properties. Only two directly belong to people.

Tucked away near the easternmost edge of the city of Atherton is a block of two dozen properties. Only two directly belong to people.

In November 1880, just three years before his death, Karl Marx wrote a letter to his friend Friedrich Adolph Sorge, a German émigré and labor organizer who had recently helped found the first socialist political party in the United States. After commenting at length on various developments in Russia, France and Germany, Marx added a postscript: “I should be very much pleased if you could find me something good (meaty) on economic conditions in California, of course at my expense. California is very important for me because nowhere else has the upheaval most shamelessly caused by capitalist centralization taken place with such speed.”

In November 1880, just three years before his death, Karl Marx wrote a letter to his friend Friedrich Adolph Sorge, a German émigré and labor organizer who had recently helped found the first socialist political party in the United States. After commenting at length on various developments in Russia, France and Germany, Marx added a postscript: “I should be very much pleased if you could find me something good (meaty) on economic conditions in California, of course at my expense. California is very important for me because nowhere else has the upheaval most shamelessly caused by capitalist centralization taken place with such speed.” Amazon's Zoox is claiming a world's first by deploying a robotaxi on public roads while only carrying passengers.

Amazon's Zoox is claiming a world's first by deploying a robotaxi on public roads while only carrying passengers.