It was a cloudy Seattle day in late 1980, and Bill Gates, the young chairman of a tiny company called Microsoft, had an appointment with IBM that would shape the destiny of the industry for decades to come.

He went into a room full of IBM lawyers, all dressed in immaculately tailored suits. Bill’s suit was rumpled and ill-fitting, but it didn’t matter. He wasn’t here to win a fashion competition.

Over the course of the day, a contract was worked out whereby IBM would purchase, for a one-time fee of about $80,000, perpetual rights to Gates’ MS-DOS operating system for its upcoming PC. IBM also licensed Microsoft’s BASIC programming language, all that company's other languages, and several of its fledging applications. The smart move would have been for Gates to insist on a royalty so that his company would make a small amount of money for every PC that IBM sold.

But Gates wasn’t smart. He was smarter.

In exchange for giving up perpetual royalties on MS-DOS, which would be called IBM PC-DOS, Gates insisted on retaining the rights to sell DOS to other companies. The lawyers looked at each other and smiled. Other companies? Who were they going to be? IBM was the only company making the PC. Other personal computers of the day either came with their own built-in operating system or licensed Digital Research’s CP/M, which was the established standard at the time.

Gates wasn’t thinking of the present, though. “The lesson of the computer industry, in mainframes, was that over time people built compatible machines,” Gates explained in an interview for the 1996 PBS documentary Triumph of the Nerds. As the leading manufacturer of mainframes, IBM experienced this phenomenon, but the company was always able to stay ahead of the pack by releasing new machines and relying on the power of its marketing and sales force to relegate the cloners to also-ran status.

The personal computer market, however, ended up working a little differently. PC Cloners were smaller, faster, and hungrier companies than their mainframe counterparts. They didn’t need as much startup capital to start building their own machines, especially after Phoenix and other companies did legal, clean-room, reverse-engineered implementations of the BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) that was the only proprietary chip in the IBM PC’s architecture. To make a PC clone, all you needed to do was put a Phoenix BIOS chip into your own motherboard design, design and manufacture a case, buy a power supply, keyboard, and floppy drive, and license an operating system. And Bill Gates was ready and willing to license you that operating system.

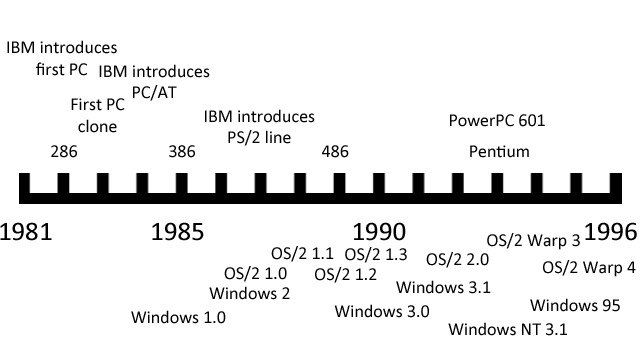

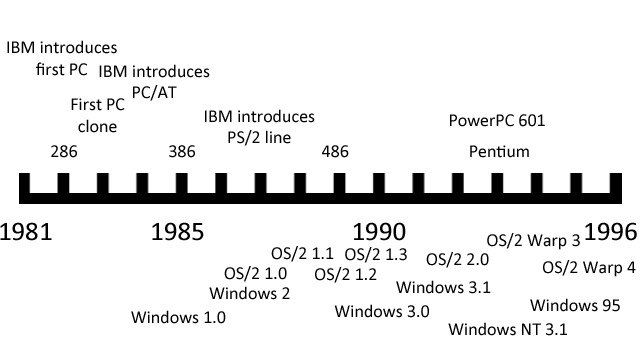

IBM went ahead and tried to produce a new model computer to stay ahead of the cloners, but the PC/AT’s day in the sun was short-lived. Intel was doing a great business selling 286 chips to clone companies, and buyers were excited to snap up 100 percent compatible AT clones at a fraction of IBM’s price.

Intel and Microsoft were getting rich, but IBM’s share of the PC pie was getting smaller and smaller each year. Something had to be done—the seeds were sown for the giant company to fight an epic battle to regain control of the computing landscape from the tiny upstarts.

IBM had only gone to Microsoft for an operating system in the first place because it was pressed for time. By 1980, the personal computing industry was taking off, causing a tiny revolution in businesses all over the world. Most big companies had, or had access to, IBM mainframes. But these were slow and clunky machines, guarded by a priesthood of technical administrators and unavailable for personal use. People would slyly bring personal computers like the TRS-80, Osborne, and Apple II into work to help them get ahead of their coworkers, and they were often religious fanatics about them. “The concern was that we were losing the hearts and minds,” former IBM executive Jack Sams said in an interview. “So the order came down from on high: give us a machine to win us back the hearts and minds.” But the chairman of IBM worried that his company’s massive bureaucracy would make any internal PC project take years to produce, by which time the personal computer industry might already be completely taken over by non-IBM machines.

So a rogue group in Boca Raton, Florida—far away from IBM headquarters—was allowed to use a radical strategy to design and produce a machine using largely off-the-shelf parts and a third-party CPU, operating system, and programming languages. It went to Microsoft to get the last two, but Microsoft didn’t have the rights to sell them an OS and directed the group to Digital Research, who was preparing a 16-bit version of CP/M that would run on the 8088 CPU that IBM was putting into the PC. In what has become a legendary story, Digital Research sent IBM’s people away when Digital Research’s lawyers refused to sign a non-disclosure agreement. Microsoft, worried that the whole deal would fall apart, frantically purchased the rights to Tim Patterson’s QDOS (“Quick and Dirty Operating System”) from Seattle Computer Products. Microsoft “cleaned up” QDOS for IBM, getting rid of the unfortunate name and allowing the IBM PC to launch on schedule. Everyone was happy, except perhaps Digital Research’s founder, Gary Kildall.

But that was all in the past. It was now 1984, and IBM had a different problem: DOS was pretty much still a quick and dirty hack. The only real new thing that had been added to it was directory support so that files could be organized a bit better on the IBM PC/AT’s new hard disk. And thanks to the deal that IBM signed in 1980, the cloners could get the exact same copy of DOS and run exactly the same software. IBM needed to design a brand new operating system to differentiate the company from the clones. Committees were formed and meetings were held, and the new operating system was graced with a name: OS/2.

Long before operating systems got exciting names based on giant cats and towns in California named after dogs, most of their names were pretty boring. IBM would design a brand new mainframe and release an operating system with a similar moniker. So the new System/360 mainframe line would run the also brand-new OS/360. It was neat and tidy, just like an IBM suit and jacket.

IBM wanted to make a new kind of PC that couldn’t be as easily cloned as its first attempt, and the company also wanted to tie it, in a marketing kind of way, to its mainframes. So instead of a Personal Computer or PC, you would have a Personal System (PS), and since it was the successor to the PC, it would be called the PS/2. The new advanced operating system would be called OS/2.

Naming an OS was a lot easier than writing it, however, and IBM management still worried about the length of time that it would take to write such a thing itself. So instead, the group decided that IBM would design OS/2 but Microsoft would write most of the actual code. Unlike last time, IBM would fully own the rights to the product and only IBM could license it to third parties.

Why would Microsoft management agree to develop a project designed to eliminate the very cash cow that made them billionaires? Steve Ballmer explained:

“It was what we used to call at the time ‘Riding the Bear.' You just had to try to stay on the bear’s back, and the bear would twist and turn and try to throw you off, but we were going to stay on the bear, because the bear was the biggest, the most important… you just had to be with the bear, otherwise you would be under the bear.”

IBM was a somewhat angry bear at the time as the tiny ferrets of the clone industry continued to eat its lunch, and many industry people started taking OS/2 very, very seriously before it was even written. What it didn’t know was that events were going to conspire to make OS/2 a gigantic failure right out of the gate.

In 1984, IBM released the PC/AT, which sported Intel’s 80286 central processor. The very next year, however, Intel released a new chip, the 80386, that was better than the 286 in almost every way.

The 286 was a 16-bit CPU that could address up to 16 megabytes of random access memory (RAM) through a 24-bit address bus. It addressed this memory in a slightly different way from its older, slower cousin the 8086, and the 286 was the first Intel chip to have memory management tools built in. To use these tools, you had to enter what Intel called “protected mode," in which the 286 opened up all 24 bits of its memory lines and went full speed. If it wasn’t in protected mode, it was in “real” mode, where it acted like a faster 8086 chip and was limited to only one megabyte of RAM (the 640KB limit was an arbitrary choice by IBM to allow for the original PC to use the extra bits of memory for graphics and other operations).

The trouble with protected mode in the 286 was that when you were in it, you couldn’t get back to real mode without a reboot. Without real mode it was very difficult to run MS-DOS programs, which expected to have full access and control of the computer at all times. Bill Gates knew everything about the 286 chip and called it “brain-damaged," but for Intel, it was a transitional CPU that led to many of the design decisions of its successor.

The 386 was Intel’s first truly modern CPU. Not only could it access a staggering 4GB of RAM in 32-bit protected mode, but it also added a “Virtual 8086” mode that could run at the same time, allowing many full instances of MS-DOS applications to operate simultaneously without interfering with each other. Today we take virtualization for granted and happily run entire banks of operating systems at once on a single machine, but in 1985 the concept seemed like it was from the future. And for IBM, this future was scary.

The 386 was an expensive chip when it was introduced, but IBM’s experience with the PC/AT told the company that the price would clearly come down over time. And a PC with a 386 chip and a proper 386-optimized operating system, running multiple virtualized applications in a huge memory space… that sounded an awful lot like a mainframe, only at PC clone prices. So should OS/2 be designed for the 386? IBM’s mainframe division came down on this idea like a ton of bricks. Why design a system that could potentially render mainframes obsolete?

So OS/2 was to run on the 286, and DOS programs would have to run one at a time in a “compatibility box” if they could be run at all. This wasn’t such a bad thing from IBM’s perspective, as it would force people to move to OS/2-native apps that much faster. So the decision was made, and Microsoft and Bill Gates would just have to live with it.

There was another problem that was happening in 1985, and both IBM and Microsoft were painfully aware of it. The launch of the Macintosh in ’84 and the Amiga and Atari ST in ’85 showed that reasonably priced personal computers were now expected to come with a graphical user interface (GUI) built in. Microsoft rushed to release the laughably underpowered Windows 1.0 in the same year so that it could have a stake in the GUI game. IBM would have to do the same or fall behind.

The trouble was that GUIs took a while to develop, and they took up more resources than their non-GUI counterparts. In a world where most 286 clones came with only 1MB RAM standard, this was going to pose a problem. Some GUIs, like the Workbench that ran on the highly advanced Amiga OS, could squeeze into a small amount of RAM, but AmigaOS was designed by a tiny group of crazy geniuses. OS/2 was being designed by a giant IBM committee. The end result was never going to be pretty.

OS/2 was plagued by delays and bureaucratic infighting. IBM rules about confidentiality meant that some Microsoft employees were unable to talk to other Microsoft employees without a legal translator between them. IBM also insisted that Microsoft would get paid by the company's standard contractor rates, which were calculated by “kLOCs," or a thousand lines of code. As many programmers know, given two routines that can accomplish the same feat, the one with fewer lines of code is generally superior—it will tend to use less CPU, take up less RAM, and be easier to debug and maintain. But IBM insisted on the kLOC methodology.

All these problems meant that when OS/2 1.0 was released in December 1987, it was not exactly the leanest operating system on the block. Worse than that, the GUI wasn’t even ready yet, so in a world of Macs and Amigas and even Microsoft Windows, OS/2 came out proudly dressed up in black-and-white, 80-column, monospaced text.

OS/2 did have some advantages over the DOS it was meant to replace—it could multitask its own applications, and each application would have a modicum of protection from the others thanks to the 286’s memory management facilities. But OS/2 applications were rather thin on the ground at launch, because despite the monumental hype over the OS, it was still starting out at ground zero in terms of market share. Even this might have been something that could be overcome were it not for the RAM crisis.

RAM prices had been trending down for years, from $880 per MB in 1985 to a low of $133 per MB in 1987. This trend sharply reversed in 1988 when demand for RAM and production difficulties in making larger RAM chips caused a sudden shortfall in the market. With greater demand and constricted supply, RAM prices shot up to over $500 per MB and stayed there for two years.

Buyers of clone computers had a choice: they could stick with the standard 1MB of RAM and be very happy running DOS programs and maybe even a Windows app (Windows 2.0 had come out in December of 1987 and while it wasn’t great, it was at least reasonable, and it did barely manage to run with that much memory). Or they could buy a copy of OS/2 1.0 Standard Edition from IBM for $325 and then pay an extra $1,000 to bump up to 3MB of RAM, which was necessary to run both OS/2 and its applications comfortably.

Needless to say, OS/2 was not an instant smash hit in the marketplace.

But wait. Wasn’t OS/2 supposed to be a differentiator for IBM to sell its shiny new PS/2 computers? Why would IBM want to sell it to the owners of clone computers anyway? Wasn’t it necessary to own a PS/2 in order to run OS/2 in the first place?

This confusion wasn’t an accident. IBM wanted people to think this way.

IBM had spent a lot of time and money developing the PS/2 line of computers, which was released in 1987, slightly before OS/2 first became available. The company ditched the old 16-bit Industry Standard Architecture (ISA), which had become the standard among all clone computers, and replaced it with its proprietary Micro Channel Architecture (MCA), a 32-bit bus that was theoretically faster. To stymie the clone makers, IBM infused MCA with the most advanced legal technology available, so much so that third-party makers of MCA expansion cards actually had to pay IBM a royalty for every card sold. In fact, IBM even tried to collect back-pay royalties for ISA cards that had been sold in the past.

The PS/2s also were the first PCs to switch over to 3.5-inch floppy drives, and they also pioneered the little round connectors for the keyboard and mouse that remain on some motherboards to this day. They were attractively packaged and fairly reasonably priced at the low end, but the performance just wasn’t there. The PS/2 line started with the Models 25 and 30, which had no Micro Channel and only a lowly 8086 running at conservatively slow clock speeds. They were meant to get buyers interested in moving up to the Models 50 and 60, which used 286 chips and had MCA slots, and the high-end Models 70 and 80, which came with a 386 chip and a jaw-droppingly high price tag to go with it. You could order the Model 50 and higher with OS/2 once it became available. You didn’t just have to stick with the “Standard Edition" either. IBM also offered an “Extended Edition” of OS/2 that came equipped with a communications suite, networking tools, and an SQL manager. The Extended Edition would only run on true-blue IBM PS/2 computers—no clones were allowed to that fancy dress party.

These machines were meant to wrestle control of the PC industry away from the clone makers, but they were also meant to subtly push people back toward a world where PCs were the servants and mainframes were the masters. They were never allowed to be too fast or run a proper operating system that would take advantage of the 32-bit computing power available with the 386 chip. In trying to do two contradictory things at once, they failed at both.

The clone industry decided not to bother tangling with IBM’s massive legal department and simply didn’t try to clone the PS/2 on anything other than a cosmetic level. Sure, they couldn’t have the shiny new MCA expansion slots, but since MCA cards were rare and expensive and the performance was throttled back anyway, it wasn’t so bad to stick with ISA slots instead. Compaq even brought together a consortium of PC clone vendors to create a new standard bus called EISA, which filled in the gaps at the high end until other standards became available. And the crown jewel of the PS/2, the OS/2 operating system, was late. It was also initially GUI-less, and when the GUI did come with the release of OS/2 1.1 in 1988, it required too much RAM to be economically viable for most users.

As the market shifted and the clone makers started selling more and more fast and cheap 386 boxes with ISA slots, Bill Gates took one of his famous “reading week” vacations and emerged with the idea that OS/2 probably didn’t have a great future. Maybe the IBM Bear was getting ready to ride straight off a cliff. But how does one disentangle from riding a bear, anyway? The answer was "very, very carefully."

It was late 1989, and Microsoft was hard at work putting the final touches on what the company knew was the best release of Windows yet. Version 3.0 was going to up the graphical ante with an exciting new 3D beveled design (which had first appeared with OS/2 1.2) and shiny new icons, and it would support Virtual 8086 mode on a 386, making it easier for people to spend more time in Windows and less time in DOS. It was going to be an exciting product, and Microsoft told IBM so.

IBM still saw Microsoft as a partner in the operating systems business, and it offered to help the smaller company by doing a full promotional rollout of Windows 3.0. But in exchange, IBM wanted to buy out the rights to the software itself, nullifying the DOS agreement that let Microsoft license to third parties. Bill Gates looked at this and thought about it carefully—and he decided to walk away from the deal.

IBM saw this as a betrayal and circulated internal memos that the company would no longer be writing any third-party applications for Windows. The separation was about to get nasty.

Unfortunately, Microsoft still had contractual obligations for developing OS/2. IBM, in a fit of pique, decided that it no longer needed the software company’s help. In an apt twist given the operating system’s name, the two companies decided to split OS/2 down the middle. At the time, this parting of the ways was compared to a divorce.

IBM would take over the development of OS/2 1.x, including the upcoming 1.3 release that was intended to lower RAM requirements. It would also take over the work that had already been done on OS/2 2.0, which was the long-awaited 32-bit rewrite. By this time, IBM finally bowed to the inevitable and admitted its flagship OS really needed to be detached from the 286 chip.

Microsoft would retain its existing rights to Windows, minus IBM’s marketing support, and the company would also take over the rights to develop OS/2 3.0. This was known internally as OS/2 NT, a pie-in-the-sky rewrite of the operating system that would have some unspecified “New Technology” in it and be really advanced and platform-independent. It might have seemed that IBM was happy to get rid of the new high-end variant of OS/2 given that it would also encroach on mainframe territory, but in fact IBM had high-end plans of its own.

OS/2 1.3 was released in 1991 to modest success, partly because RAM prices finally declined and the new version didn’t demand quite so much of it. However, by this time Windows 3 had taken off like a rocket. It looked a lot like OS/2 on the surface, but it cost less, took fewer resources, and didn’t have a funny kind-of-but-not-really tie-in to the PS/2 line of computers. Microsoft also aggressively courted the clone manufacturers with incredibly attractive bundling deals, putting Windows 3 on most new computers sold.

IBM was losing control of the PC industry all over again. The market hadn’t swung away from the clones, and it was Windows, not OS/2, that was the true successor to DOS. If the bear had been angry before, now it was outraged. It was going to fight Microsoft on its own turf, hoping to destroy the Windows upstart forever. The stage was set for an epic battle.

IBM had actually been working on OS/2 2.0 for a long time in conjunction with Microsoft, and a lot of code was already written by the time the two companies split up in 1990. This enabled IBM to release OS/2 2.0 in April of 1992, a month after Microsoft launched Windows 3.1. Game on.

OS/2 2.0 was a 32-bit operating system, but it still contained large portions of 16-bit code from its 1.x predecessors. The High Performance File System (HPFS) was one of the subsystems that was still 16-bit, along with many device drivers and the Graphics Engine that ran the GUI. Still, the things that needed to be in 32-bit code were, like the kernel and the memory manager.

IBM had also gone on a major shopping expedition for any kind of new technologies that might help make OS/2 fancier and shinier. It had partnered with Apple to work on next-generation OS technologies and licensed NeXTStep from Steve Jobs. While technology from these two platforms didn’t directly make it into OS/2, a portion of code from the Amiga did: IBM gave Commodore a license to its REXX scripting language in exchange for some Amiga technology and GUI ideas, and included them with OS/2 2.0.

At the time, the hottest industry buzzword was “object-oriented.” While object-oriented programming had been around for many years, it was just starting to gain traction on personal computers. IBM itself was a veteran of object-oriented technology, having developed its own Smalltalk implementation called Visual Age in the 1980s. So it made sense that IBM would want to trumpet OS/2 as being more object-oriented than anything else. The tricky part of this task is that object orientation is mostly an internal technical matter of how program code is constructed and isn’t visible by end users.

IBM decided to make the user interface of OS/2 2.0 behave in a manner that was “object oriented.” This project ended up being called the Workplace Shell, and it became, simultaneously, the number one feature that OS/2 fans both adored and despised.

As the default desktop of OS/2, 2.0 was rather plain and the icons weren’t especially striking, it was not immediately obvious what was new and different about the Workplace Shell. As soon as you started using it, however, you saw that it was very different from other GUIs. Right-clicking on any icon brought up a contextual menu, something that hadn’t been seen before. Icons were considered to be “objects,” and you could do things with them that were vaguely object-like. Drag an icon to the printer icon and it printed. Drag an icon to the shredder and it was deleted (yes, permanently!) There was a strange icon called “Templates” that you could open up and then “drag off” blank sheets that, if you clicked on them, would open up various applications (the Apple Lisa had done something similar in 1983). Was that object-y enough for OS/2? No. Not nearly enough.

Each folder window could have various things dragged to it, and they would have different actions. If you dragged in a color from the color palette, the folder would now have that background color. You could do the same with wallpaper bitmaps. And fonts. In fact, you could do all three and quickly change any folder to a hideous combination, and each folder could be differently styled in this fashion.

In practice, this was something you either did by accident and then didn’t know how to fix or did once to demo it to a friend and then never did it again. These kinds of features were flashy, but they took up a lot of memory, and computers in 1992 were still typically sold with 2MB or 4MB of RAM.

The minimum requirement of OS/2 2.0, as displayed on the box (and a heavy box it was, coming with no less than 21 3.5-inch floppy disks!), was 4MB of RAM. I once witnessed my local Egghead dealer trying to boot up OS/2 on a system with that much RAM. It wasn’t pretty. The operating system started thrashing to disk to swap out RAM before it was even finished booting. Then it would try to boot some more. And swap. And boot. And swap. It probably took over 10 minutes to get to a functional desktop, and guess what happened if you right-clicked a single icon? It swapped. Basically, OS/2 2.0 in this amount of RAM was unusable.

At 8MB the system worked as advertised, and at 16MB it would run comfortably without excessive thrashing. Fortunately, RAM was down to around $30 per MB by this time, so upgrading wasn’t as huge a deal as it was in the OS/2 1.x days. Still, it was a barrier to adoption, especially as Windows 3.1 ran happily in 2MB.

But Windows 3.1 was also a crash-happy, cooperative multitasking facade of an operating system with a strange, bifurcated user interface that only Bill Gates could love. OS/2 aspired to do something better. And in many ways, it did.

Despite the success of the original PC, IBM was never really a consumer company and never really understood marketing to individual people. The PS/2 launch, for example, was accompanied by an advertising push that featured the aging and somewhat befuddled cast of the 1970s TV series M*A*S*H.

This tone-deaf approach to marketing continued with OS/2. Exactly what was it, and how did it make your computer better? Was it enough to justify the extra cost of the OS and the RAM to run it well? Superior multitasking was one answer, but it was hard to understand the benefits by watching a long and boring shot of a man playing snooker. The choice of advertising spending was also somewhat curious. For years, IBM paid to sponsor the Fiesta Bowl, and it spent most of OS/2’s yearly ad budget on that one venue. Were college football fans really the best audience for multitasking operating systems?

Eventually IBM settled on a tagline for OS/2 2.0: “A better DOS than DOS, and a better Windows than Windows.” This was definitely true for the first claim and arguably true for the second. It was also a tagline that ultimately doomed the operating system.

OS/2 had the best DOS virtual machine ever seen at the time. It was so good that you could easily run DOS games fullscreen while multitasking in the background, and many games (like Wing Commander) even worked in a 320x200 window. OS/2’s DOS box was so good that you could run an entire copy of Windows inside it, and thanks to IBM’s separation agreement with Microsoft, each copy of OS/2 came bundled with something IBM called “Win-OS2.” It was essentially a free copy of Windows that ran either full-screen or windowed. If you had enough RAM, you could run each Windows app in a completely separate virtual machine running its own copy of Windows, so a single app crash wouldn’t take down any of the others.

This was a really cool feature, but it made it simple for GUI application developers to decide which operating system to support. OS/2 ran Windows apps really well out of the box, so they could just write a Windows app and both platforms would be able to run that app. On the other hand, writing a native OS/2 application was a lot of work for Windows developers. The underlying application programming interfaces (APIs) were very different between the two: Windows used a barebones set of APIs called Win16, while OS/2 had a more expansive set with the unwieldy name of Presentation Manager. The two differed in many ways, even in terms of whether you counted the number of pixels to position a window from the top or from the bottom of the screen.

Some companies did end up making native OS/2 Presentation Manager applications, but they were few and far between. IBM was one, of course, and it was joined by Lotus, who was still angry at Microsoft for its alleged efforts against the company in the past. Really, though, what angered Lotus (and others, like Corel) about Microsoft was the sudden success of Windows and the skyrocketing sales of Microsoft applications that ran on it: Word, Excel, and PowerPoint. In the DOS days, Microsoft made the operating system for PCs, but it was an also-ran in the application side of things. As the world shifted to Windows, Microsoft was pushing application developers aside. Writing apps for OS/2 was one way to fight back.

It was also an opening for startup companies who didn’t want to struggle against Microsoft for a share of the application pie. One of these companies was DeScribe, who made a very good word processor for OS/2 (that I once purchased with my own money on a student budget). For an aspiring writer, DeScribe offered a nice clean writing slate that supported long filenames. Word for Windows, like Windows itself, was still limited to eight characters.

Unfortunately, the tiny companies like DeScribe ended up doing a much better job with their applications than the established giants like Lotus and Corel. The OS/2 versions of 1-2-3 and Draw were slow, memory-hogging, and buggy. This put an even bigger wet blanket over the native OS/2 applications market. Why buy a native app when the Windows version ran faster and better and could run seamlessly in Win-OS2?

As things got more desperate on the native applications front, IBM even started paying developers to write OS/2 apps. (Borland was the biggest name in this effort.) This worked about as well as you might expect: Borland had no incentive to make its apps fast or bug-free, just to ship them as quickly as possible. They barely made a dent in the market.

Still, although OS/2’s native app situation was looking dire, the operating system itself was selling quite well, reaching one million sales and hitting many software best-seller charts. Many users became religious fanatics about how the operating system could transform the way you used your computer. And compared to Windows 3.1, it was indeed a transformation. But there was another shadow lurking on the horizon.

When faced with a bear attack, most people would run away. Microsoft’s reaction to IBM’s challenge was to run away, build a fort, then build a bigger fort, then build a giant metal fortress armed with automatic weapons and laser cannons.

In 1993, Microsoft released Windows for Workgroups 3.11, which bundled small business networking with a bunch of small fixes and improvements, including some 32-bit code. While it did not sell well immediately (a Microsoft manager once joked that the internal name for the product was "Windows for Warehouses"), it was a significant step forward for the product. Microsoft was also working on Windows 4.0, which was going to feature much more 32-bit code, a new user interface, and pre-emptive multitasking. It was codenamed Chicago.

Finally, and most importantly for the future of the company, Bill Gates hired the architect of the industrial-strength minicomputer operating system VMS and put him in charge of the OS/2 3.0 NT group. Dave Cutler’s first directive was to throw away all the old OS/2 code and start from scratch. The company wanted to build a high-performance, fault-tolerant, platform-independent, and fully networkable operating system. It would be known as Windows NT.

IBM was aware of Microsoft’s plans and started preparing a new major release of OS/2 aimed squarely at them. Windows 4.0 was experiencing several public delays, so IBM decided to take a friendly bear swipe at its opponent. The third beta of OS/2 3.0 (thankfully, now delivered on a CD-ROM) was emblazoned with the words “Arrive in Chicago earlier than expected.”

OS/2 version 3.0 would also come with a new name, and unlike codenames in the past, IBM decided to put it right on the box. It was to be called OS/2 Warp. Warp stood for "warp speed," and this was meant to evoke power and velocity. Unfortunately, IBM’s famous lawyers were asleep on the job and forgot to run this by Paramount, owners of the Star Trek license. It turns out that IBM would need permission to simulate even a generic “jump to warp speed” on advertising for a consumer product, and Paramount wouldn’t give it. IBM was in a quandary. The name was already public, and the company couldn’t use Warp in any sense related to spaceships. IBM had to settle for the more classic meaning of Warp—something bent or twisted. This, needless to say, isn’t exactly the impression you want to give for a new product. At the launch of OS/2 Warp in 1994, Patrick Stewart was supposed to be the master of ceremonies, but he backed down and IBM was forced to settle for Voyager captain Kate Mulgrew.

OS/2 Warp came in two versions: one with a blue spine on the box that contained a copy of Win-OS2 and one with a red spine that required the user to use the copy of Windows that they probably already had to run Windows applications. The red-spined box was considerably cheaper and became the best-selling version of OS/2 yet.

However, Chicago, now called Windows 95, was rapidly approaching, and it was going to be nothing but bad news for IBM. It would be easy to assume, but not entirely correct, that Windows won over OS/2 because of IBM’s poor marketing efforts. It would be somewhat more correct to assume that Windows won out because of Microsoft’s aggressive courting of the clone computer companies. But the brutal, painful truth, at least for an OS/2 zealot like me, was that Windows 95 was simply a better product.

For several months, I dual-booted both OS/2 Warp and a late beta of Windows 95 on the same computer: a 486 with 16MB of RAM. After extensive testing, I was forced to conclude that Windows 95, even in beta form, was faster and smoother. It also had better native applications and (this was the real kicker) crashed less often.

How could this be? OS/2 Warp was now a fully 32-bit operating system with memory protection and preemptive multitasking, whereas Windows 95 was still a horrible mutant hybrid of 16-bit Windows with 32-bit code. By all rights, OS/2 shouldn’t have crashed—ever. And yet it did. All the time.

Unfortunately, OS/2 had a crucial flaw in its design: a Synchronous Input Queue (SIQ). What this meant was that all messages to the GUI window server went through a single tollbooth. If any OS/2 native GUI app ever stopped servicing its window messages, the entire GUI would get stuck and the system froze. OK, technically the operating system was still running. Background tasks continued to execute just fine. You just couldn’t see them or interact with them or do anything, because the entire GUI was hung. Some enterprising OS/2 fan wrote an application that polled the joystick port and was supposed to unstick things when the user pressed a button. It rarely worked.

Ironically, if you never ran native OS/2 applications and just ran DOS and Windows apps in a VM, the operating system was much more stable.

OS/2’s fortune wasn’t helped by reports that users of IBM’s own Aptiva series had trouble installing it on their computers. IBM’s PC division also needed licenses from Microsoft to bundle Windows 95 with its systems, and Microsoft got quite petulant with its former partner, even demanding at one point that IBM stop all development on OS/2. IBM’s PC division ended up signing a license the same day that Windows 95 was released.

Microsoft really didn’t need to stoop to these levels. Windows 95 was a smash success, breaking all previous records for sales of operating systems. It changed the entire landscape of computing. Commodore and Atari were now out of the picture, and Apple was sent reeling by Windows 95’s success. IBM was in for the fight of its life, and its main weapon wasn’t up to snuff.

IBM wouldn’t give up the fight just yet, however. Big Blue had plans for taking back its rightful place at the head of the computing industry, and it was going to ally with everyone who wasn’t Microsoft if it could help it.

First up on its list of companies to crush: Intel. IBM, along with Sun, had been an early pioneer of a new type of microprocessor design called Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC). Basically, the idea was to cut out long and complicated instructions in favor of simpler tasks that could be done more quickly. IBM created a CPU called POWER (Performance Optimization With Enhanced RISC) and used it in its line of very expensive workstations.

IBM had already started a collaboration with Apple and Motorola to bring its groundbreaking POWER RISC processor technology to the desktop, and it used this influence to join Apple’s new operating system development project, which was then codenamed “Pink." The new OS venture was renamed Taligent, and the prospective kernel changed from an Apple-designed microkernel called Opus to a microkernel that IBM was developing for an even grander operating system that it named Workplace OS.

Workplace OS was to be the Ultimate Operating System, the OS to end all OSes. It would run on the Mach 3.0 microkernel developed at Carnegie Mellon University, and on top of that, the OS would run various “personalities,” including DOS, Windows, Macintosh, OS/400, AIX, and of course OS/2. It would run on every processor architecture under the sun, but it would mostly showcase the power of POWER. It would be all-singing and all-dancing.

And IBM never quite got around to finishing it.

Meanwhile, Dave Cutler’s team at Microsoft already shipped the first version of Windows NT (version 3.1) in July of 1993. It had higher resource requirements than OS/2, but it also did a lot more: it supported multiple CPUs, and it was multiplatform, ridiculously stable and fault-tolerant, fully 32-bit with an advanced 64-bit file system, and compatible with Windows applications. (It even had networking built in.) Windows NT 3.5 was released a year later, and a major new release with the Windows 95 user interface was planned for 1996. While Windows NT struggled to find a market in the early days of its life, it did everything it was advertised to do and ended up merging with the consumer Windows 9x series by 2001 with the release of Windows XP.

In the meantime, the PowerPC chip, which was based on IBM’s POWER designs (but was much cheaper), was released in partnership with Motorola and ended up saving Apple’s Macintosh division. However, plans to release consumer PowerPC machines to run other operating systems were perpetually delayed. One of the main problems was a lack of alternate operating systems. Taligent ran into development hell, was repositioned as a development environment, and was then canned completely. IBM hastily wrote an experimental port of OS/2 Warp for PowerPC, but abandoned it before it was finished. Workplace OS never got out of early alpha stages. Ironically, Windows NT was the only non-Macintosh consumer operating system to ship with PowerPC support. But the advantages of running a PowerPC system with Windows NT over an Intel system running Windows NT were few. The PowerPC chip was slightly faster, but it required native applications to be recompiled for its instruction set. Windows application vendors saw no reason to recompile their apps for a new platform, and most of them didn’t.

So to sum up: the new PowerPC was meant to take out Intel, but it didn’t do anything beyond saving the Macintosh. The new Workplace OS was meant to take out Windows NT, but IBM couldn’t finish it. And OS/2 was meant to take out Windows 95, but the exact opposite happened.

In 1996, IBM released OS/2 Warp 4, which included a revamped Workplace Shell, bundled Java and development tools, and a long-awaited fix for the Synchronous Input Queue. It wasn’t nearly enough. Sales of OS/2 dwindled while sales of Windows 95 continued to rise. IBM commissioned an internal study to reevaluate the commercial potential of OS/2 versus Windows, and the results weren’t pretty. The order came down from the top of the company: the OS/2 development lab in Boca Raton would be eliminated, Workplace OS would be killed, and over 1,300 people would lose their jobs. The Bear, beaten and bloodied, had left the field.

IBM would no longer develop new versions of OS/2, although it continued selling it until 2001. Who was buying it? Mostly banks, who were still wedded to IBM’s mainframes. The banks mostly used it in their automated teller machines, but Windows NT eventually took over this tiny market as well. After 2001, IBM stopped selling OS/2 directly and instead utilized Serenity Systems, one of its authorized business dealers, who rechristened the operating system as eComStation. You can still purchase eComStation today (some people do), but copies are very, very rare. Serenity Systems continues to release updates that add driver support for modern hardware, but the company is not actively developing the operating system itself. There simply isn’t enough demand to make such an enterprise profitable.

In December 2004, IBM announced that it was selling its entire PC division to the Chinese company Lenovo, marking the definitive end of a 23-year reign of selling personal computers. For nearly 10 of those 23 years, IBM tried in vain to replace the PC’s Microsoft-owned operating system with one of its own. Ultimately, it failed.

Many OS/2 fans petitioned IBM for years to free up the operating system’s code base to an open source license, but IBM has steadily refused. The company is probably unable to, as OS/2 still contains large chunks of proprietary code belonging to other companies—most significantly, Microsoft.

Most people who want to use OS/2 today are coming from a historical interest only, and their task is made more difficult by the fact that OS/2 has difficulty running under virtual machines such as VMWare. A Russian company was hired by a major bank in Moscow in the late 1990s to find a solution for their legacy OS/2 applications. It ended up writing its own virtual machine solution that became Parallels, a popular application that today allows Macintosh users to run Windows apps on OSX. In an eerie way, running Parallels today reminds me a lot of running Win-OS2 on OS/2 in the mid-1990s. Apple, perhaps wisely, has never bundled Parallels with its Mac computers.

So why did IBM fail so badly with OS/2? Why was Microsoft able to deftly cut IBM out of the picture and then beat it to death with Windows? And more importantly, are there any lessons from this story that might apply to hardware and software companies today?

IBM ignored the personal computer industry long enough that it was forced to rush out a PC design that was easy (and legal) to clone. Having done so, the company immediately wanted to put the genie back in the bottle and take the industry back from the copycats. When IBM announced the PS/2 and OS/2, many industry pundits seriously thought the company could do it.

Unfortunately, IBM was being pulled in two directions. The company's legacy mainframe division didn’t want any PCs that were too powerful, lest they take away the market for big iron. The PC division just wanted to sell lots of personal computers and didn’t care what it had to do in order to meet that goal. This fighting went back and forth, resulting in agonizing situations such as IBM’s own low-end Aptivas being unable to run OS/2 properly and the PC division promoting Windows instead.

IBM always thought that PCs would be best utilized as terminals that served the big mainframes it knew and loved. OS/2’s networking tools, available only in the Extended Edition, were mostly based on the assumption that PCs would connect to big iron servers that did the heavy lifting. This was a “top-down” approach to connecting computers together. In contrast, Microsoft approached networking from a “bottom-up” approach where the server was just another PC running Windows. As personal computing power grew and more robust versions of Windows like NT became available, this bottom-up approach became more and more viable. It's certainly much less expensive.

IBM also made a crucial error in promoting OS/2 as a “better DOS than DOS and a better Windows than Windows.” Having such amazing compatibility with other popular operating systems out of the box meant that the market for native OS/2 apps never had a chance to develop. Many people bought OS/2. Very few people bought OS/2 applications.

The book The Innovator’s Dilemma makes a very good case that big companies with dominant positions in legacy markets are institutionally incapable of shifting over to a new disruptive technology, even though those companies frequently invent said technologies themselves. IBM invented more computer technologies and holds more patents than any other computer company in history. Still, when push came to shove, it gave up the personal computer in favor of hanging on to the mainframe. IBM still sells mainframes today and makes good money doing so, but the company is no longer a force in personal computers.

Today, many people have observed that Microsoft is the new dominant force in legacy computing, with legacy redefined as a personal computer running Windows. The new disruptive force is smartphones and tablets, an area in which Apple and Google have become the new dominant forces. Microsoft, to its credit, responded as quickly as it was able to meet this new disruption. The company even re-designed its legacy user interface (the Windows desktop) to be more suited to tablets.

It could be argued that Microsoft was slow to act, just as IBM was. It could also be argued that Windows Phone and Surface tablets have failed to capture market share against iOS and Android in the same way that OS/2 failed to beat back Windows. However, there is one difference that separates Microsoft from most legacy companies: the company doesn’t give up. IBM threw in the towel on OS/2 and then on PCs in general. Microsoft is willing to spend as many billions as it takes in order to claw its way back to a position of power in the new mobile landscape. Microsoft still might not succeed, but for now at least, it's going to keep trying.

The second lesson of OS/2—to not be too compatible out of the box with rival operating systems—is a lesson that today’s phone and tablet makers should take seriously. Blackberry once touted that you could easily run Android apps on its BB10 operating system, but that ended up not helping the company at all. Alternative phone operating system vendors should think very carefully before building in Android app compatibility, lest they suffer the same fate as OS/2.

The story of OS/2 is now fading into the past. In today’s fast-paced computing environment, it may not seem particularly relevant. But it remains a story of how a giant, global mega-corporation tried to take on a young and feisty upstart and ended up retreating in utter defeat. Such stories are rare, and because of that rarity they become more precious. It’s important to remember that IBM was not the underdog. It had the resources, the technology, and the talent to crush the much smaller Microsoft. What it didn’t have was the will.

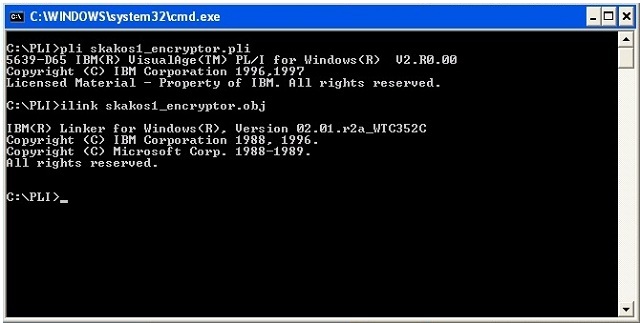

The computer revolution has always been driven by the new and the next. The hype-mongers have trained us to assume that the latest iteration of ideas will be the next great leap forward. Some, though, are quietly stepping off the hype train. Whereas the steady stream of new programming languages once attracted all the attention, lately it’s more common to find older languages like Ada and C reclaiming their top spots in the popular language indexes. Yes, these rankings are far from perfect, but they’re a good litmus test of the respect some senior (even ancient) programming languages still command.

The computer revolution has always been driven by the new and the next. The hype-mongers have trained us to assume that the latest iteration of ideas will be the next great leap forward. Some, though, are quietly stepping off the hype train. Whereas the steady stream of new programming languages once attracted all the attention, lately it’s more common to find older languages like Ada and C reclaiming their top spots in the popular language indexes. Yes, these rankings are far from perfect, but they’re a good litmus test of the respect some senior (even ancient) programming languages still command. For decades, programming has meant writing code. Crafting lines of cryptic script written by human hands to make machines do our bidding. From the earliest punch cards to today's most advanced programming languages, coding has always been about control. Precision. Mastery. Elegance. Art.

For decades, programming has meant writing code. Crafting lines of cryptic script written by human hands to make machines do our bidding. From the earliest punch cards to today's most advanced programming languages, coding has always been about control. Precision. Mastery. Elegance. Art. On stage at Microsoft’s 50th anniversary celebration in Redmond earlier this month, CEO Satya Nadella showed a video of himself retracing the code of the company’s first-ever product, with help from AI.

On stage at Microsoft’s 50th anniversary celebration in Redmond earlier this month, CEO Satya Nadella showed a video of himself retracing the code of the company’s first-ever product, with help from AI. My good old friend and colleague Mike who in the late 2000s built an application for his colleagues that he described as a "content migration toolset." The app was so good that customers started asking for it and Mike's employer decided to commercialize it.

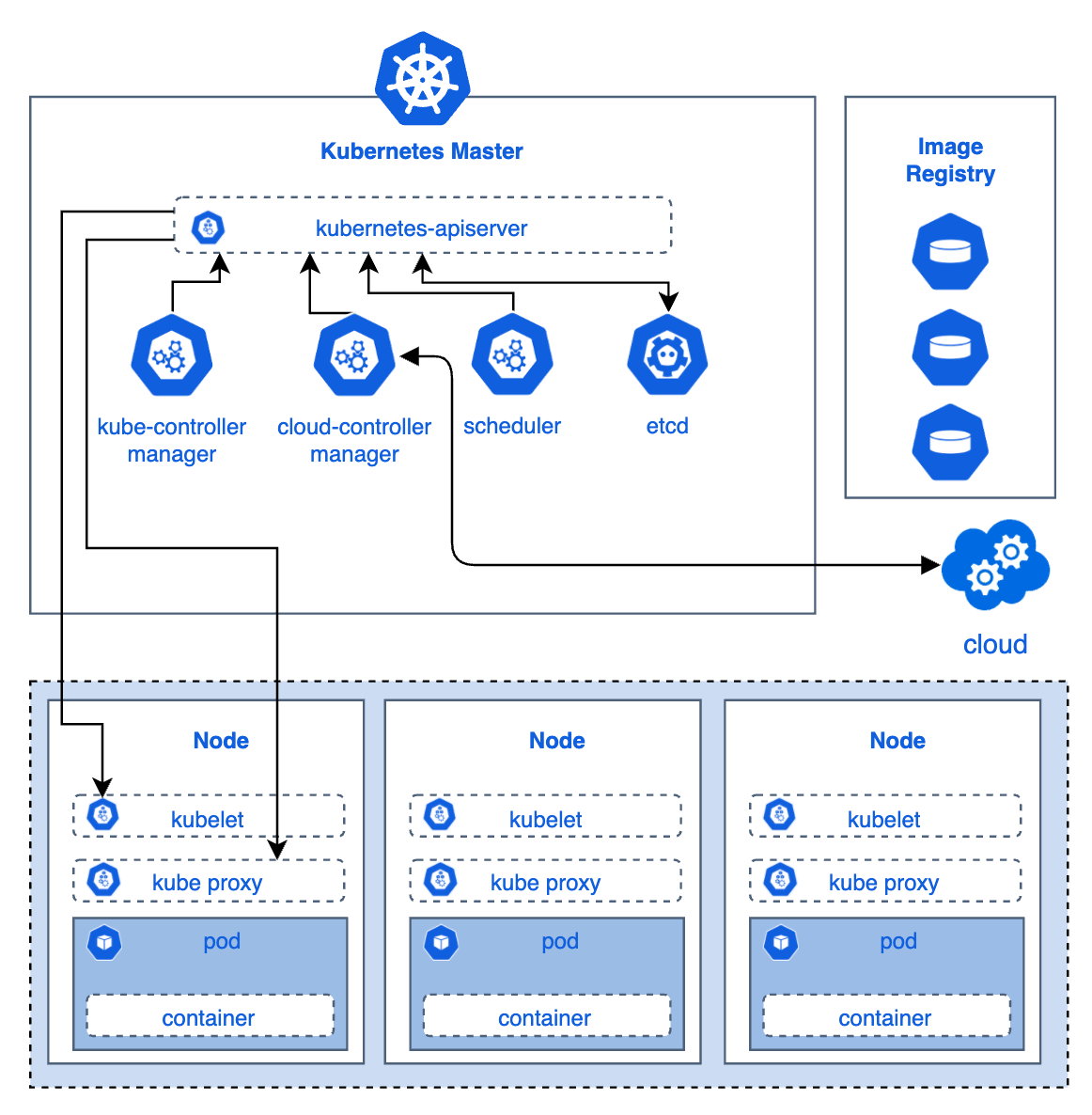

My good old friend and colleague Mike who in the late 2000s built an application for his colleagues that he described as a "content migration toolset." The app was so good that customers started asking for it and Mike's employer decided to commercialize it. Containers seem to be the default approach for most systems migrating to the cloud or being built there, and for good reasons. They provide portability and scalability (using Kubernetes orchestration) that is more difficult to achieve with other enabling technology. Moreover, there is a healthy ecosystem around containers, and a solution is easier to define.

Containers seem to be the default approach for most systems migrating to the cloud or being built there, and for good reasons. They provide portability and scalability (using Kubernetes orchestration) that is more difficult to achieve with other enabling technology. Moreover, there is a healthy ecosystem around containers, and a solution is easier to define.

It was a cloudy Seattle day in late 1980, and Bill Gates, the young chairman of a tiny company called Microsoft, had an appointment with IBM that would shape the destiny of the industry for decades to come.

It was a cloudy Seattle day in late 1980, and Bill Gates, the young chairman of a tiny company called Microsoft, had an appointment with IBM that would shape the destiny of the industry for decades to come. There's a best first programming to learn in the first place? I'd argue, given that the essentials of programming are prevalent in any language, it really doesn't matter which one you learn first.

There's a best first programming to learn in the first place? I'd argue, given that the essentials of programming are prevalent in any language, it really doesn't matter which one you learn first. A new study shows that, in tech, over one-third of professionals admit they have issues with depression. Specifically, 38.8 percent of tech pros responding to a Blind survey say they’re depressed. When you tie employers into this, the main offenders are Amazon and Microsoft, where 43.4 percent and 41.58 percent (respectively) of employees say they’re depressed. Intel rounds out the top three with 38.86 percent of its respondents reporting issues with depression.

A new study shows that, in tech, over one-third of professionals admit they have issues with depression. Specifically, 38.8 percent of tech pros responding to a Blind survey say they’re depressed. When you tie employers into this, the main offenders are Amazon and Microsoft, where 43.4 percent and 41.58 percent (respectively) of employees say they’re depressed. Intel rounds out the top three with 38.86 percent of its respondents reporting issues with depression.

Business PCs went mainstream in the 1990s. At the beginning of the decade, most people didn’t use PCs in offices. By 2000, pretty much all office work involved PCs. The use of mice and keyboards and the necessity of sitting and using a PC all day caused a pandemic of repetitive stress injuries, including carpal tunnel syndrome. It seems as if everybody got injured by their PCs at some point. It was common back then to see people wearing wrist braces. Companies invested in wrist pads, ergonomic mice and keyboards, and special foot rests. Insurance claims for medical treatment for carpal tunnel exploded. Then the 2000s hit. Mobile devices took off. Business technology use was diversified into laptops, BlackBerry pagers, PDAs and cellphones. We stopped hearing about carpal tunnel and starting hearing about “texting thumb” and other repetitive stress injuries related to typing on a phone or pager. Around ten years ago, the technology health problems shifted from the physical to the mental. Employees started suffering from all kinds of psychological syndromes, from nomophobia (fear of being without a phone) to phantom vibration syndrome (where you think you feel your phone vibrating even though your phone isn’t there) to screen insomnia to smartphone addiction. In recent years, our smartphones have begun harming health by giving us social media all day and all night, with notifications and alerts telling us something is happening. Millions of people are now suffering from smartphone addiction, which is really social media addiction, and, as I detailed in this space, it’s harming productivity, health and happiness.

Business PCs went mainstream in the 1990s. At the beginning of the decade, most people didn’t use PCs in offices. By 2000, pretty much all office work involved PCs. The use of mice and keyboards and the necessity of sitting and using a PC all day caused a pandemic of repetitive stress injuries, including carpal tunnel syndrome. It seems as if everybody got injured by their PCs at some point. It was common back then to see people wearing wrist braces. Companies invested in wrist pads, ergonomic mice and keyboards, and special foot rests. Insurance claims for medical treatment for carpal tunnel exploded. Then the 2000s hit. Mobile devices took off. Business technology use was diversified into laptops, BlackBerry pagers, PDAs and cellphones. We stopped hearing about carpal tunnel and starting hearing about “texting thumb” and other repetitive stress injuries related to typing on a phone or pager. Around ten years ago, the technology health problems shifted from the physical to the mental. Employees started suffering from all kinds of psychological syndromes, from nomophobia (fear of being without a phone) to phantom vibration syndrome (where you think you feel your phone vibrating even though your phone isn’t there) to screen insomnia to smartphone addiction. In recent years, our smartphones have begun harming health by giving us social media all day and all night, with notifications and alerts telling us something is happening. Millions of people are now suffering from smartphone addiction, which is really social media addiction, and, as I detailed in this space, it’s harming productivity, health and happiness. The Cython language is a superset of Python that compiles to C, yielding performance boosts that can range from a few percent to several orders of magnitude, depending on the task at hand. For work that is bound by Python’s native object types, the speedups won’t be large. But for numerical operations, or any operations not involving Python’s own internals, the gains can be massive. This way, many of Python’s native limitations can be routed around or transcended entirely.

The Cython language is a superset of Python that compiles to C, yielding performance boosts that can range from a few percent to several orders of magnitude, depending on the task at hand. For work that is bound by Python’s native object types, the speedups won’t be large. But for numerical operations, or any operations not involving Python’s own internals, the gains can be massive. This way, many of Python’s native limitations can be routed around or transcended entirely.

In its 2017 retrospective, TIOBE names C its programming language of the year. The 45-year old (seriously!) language “appears to be the fastest grower of 2017 in the TIOBE index” with a 1.69 percent surge over the last 12 months. The TIOBE index calculation comes down to counting hits for the search query for 25 search engines. More details about definition of the TIOBE index

In its 2017 retrospective, TIOBE names C its programming language of the year. The 45-year old (seriously!) language “appears to be the fastest grower of 2017 in the TIOBE index” with a 1.69 percent surge over the last 12 months. The TIOBE index calculation comes down to counting hits for the search query for 25 search engines. More details about definition of the TIOBE index