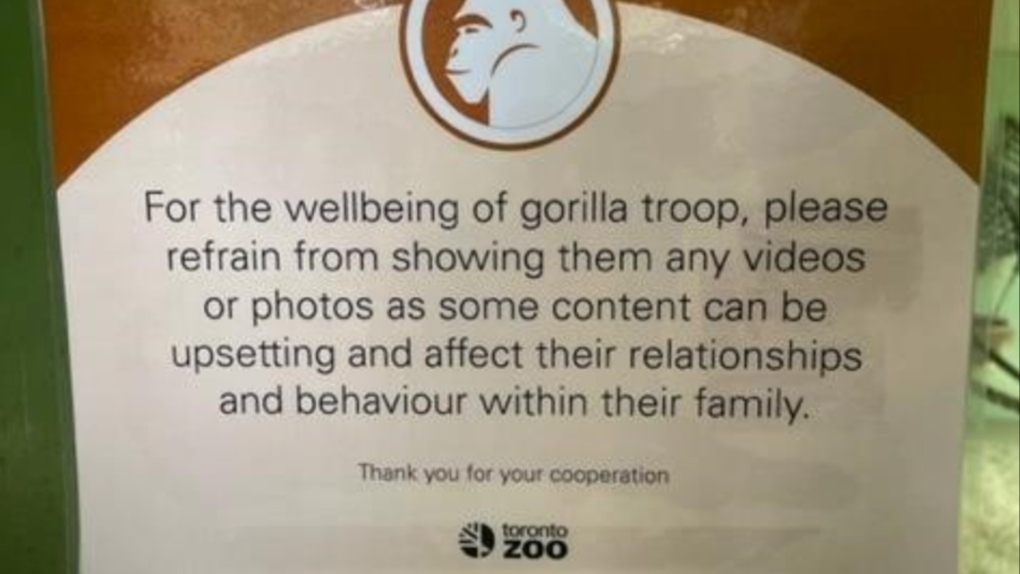

The Toronto Zoo is advising its visitors to avoid showing videos and photos on their cellphones to its gorillas as they distract the apes.

The Toronto Zoo is advising its visitors to avoid showing videos and photos on their cellphones to its gorillas as they distract the apes."We just want the gorillas to be able to be gorillas," Hollie Ross, behavioural husbandry supervisor at the zoo, said in an interview on Thursday.

"And when our guests come to the zoo, we want them to be able to see gorillas in a very natural state, and what they would be doing naturally – to sort of connect with them on that level."

Ross said one of the gorillas, Nassir, has become enthralled with videos visitors are showing him.

The Toronto Zoo's website says Nassir was born in September 2009 and describes him as "the epitome of a teenager" who is "fascinated by videos and screen time would dominate his life if he had his way."

While the gorilla's fascination with videos is primarily out of curiosity, the zoo wants to ensure that it does not become an issue, Ross said, adding that they have not observed any significant behavioural changes so far.

"We don't really want our guests coming and showing them videos. We would rather have them see them do gorilla things," she said.

"Nassir, in particular, was really interested in seeing different videos. I think, mostly, he was seeing videos of other animals. But, I think what is really important is that he's able to just hang out with his brother and be a gorilla."

A zoo in Chicago had to put up a rope line a few feet away from the glass partition of its gorilla enclosure to keep visitors from showing their phones to one of the apes who had becomeso distracted by the gadgets that officials started seeing behavioural changes, according to the Chicago Sun Times.

Ross noted the Toronto Zoo is already letting its gorillas watch videos, including those of other animals and nature documentaries, which she said they really like.

"We just want to make sure that we know the content. Very much like managing an account for a child or something, you want to make sure that your parental controls are on, and that you're in control of what the content is that they're seeing," she said.

"We just want to make sure that we know what they're watching."

History Of Masturbation

Jun. 10th, 2023 10:04 am Biologists in London have traced back the history of masturbation in primates to at least 40 million years ago, according to a new study published Wednesday in Proceedings of the Royal Society B(https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2023.0061).

Biologists in London have traced back the history of masturbation in primates to at least 40 million years ago, according to a new study published Wednesday in Proceedings of the Royal Society B(https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2023.0061).n an evolutionary sense, the behavior could seem counter-intuitive, writes Darren Incorvaia for Science News—spending time and energy on self-pleasure doesn’t appear to serve a reproductive purpose when compared to mating with another animal. But the new research suggests masturbation may benefit males by boosting reproductive success and helping avoid sexually transmitted infections.

“Historically, masturbation was considered to be either pathological or a byproduct of sexual arousal,” Matilda Brindle, an evolutionary biologist at the University College London, tells Jake Meeus-Jones of the South West News Service (SWNS). “Recorded observations were too fragmented to understand its distribution, evolutionary history or adaptive significance. Perhaps surprisingly, it seems to serve an evolutionary purpose.”

In the study, Brindle and her colleagues describe how they compiled the “largest ever dataset of primate masturbation” from 400 sources, including nearly 250 published papers and 150 responses from primatologists and zookeepers via questionnaires and personal communications, per a statement(https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/991483).

The data suggested that this autosexual behavior most likely occurred in the common ancestor of all monkeys and apes (including humans). But a scarcity of data for other primate groups, like lemurs and tarsiers, makes it unclear whether self-pleasuring behavior was also present in their ancestors, per the statement. Through modeling, the researchers sought to detail when the practice came about.

“This is a very interesting article that sheds light on the evolutionary history of behaviors that leave no trace in the fossil record,” Kit Opie, an anthropologist at the University of Bristol in England, tells New Scientist’s Soumya Sagar.

To find more clues about why masturbation arose, the team used a pair of hypotheses. The first, the “postcopulatory selection hypothesis,” suggests the behavior helps to fertilize an egg. For example, masturbation without ejaculation may increase arousal before sex. This could lead lower-ranking male monkeys to ejaculate faster and therefore have higher breeding success. Masturbation with ejaculation, on the other hand, might allow males to get rid of inferior semen, leading to higher-quality sperm that might outcompete those of other males, reports SWNS.

Another potential explanation—the “pathogen avoidance hypothesis”—suggests that male ejaculation after sex cleanses the urethra, reducing the chance of contracting an STI.

The authors are “the first to use a cross-species approach” to explore the purpose of masturbation, Lateefah Roth, a biologist at the Institute of Forensic Psychiatry and Sex Research at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany, tells Science News, adding that the paper is “a great starting point.”

The researchers found that male masturbation evolved alongside mating systems where competition between males is high. They did not find a similar trend for females—but Brindle tells Science News this may be because of a lack of data rather than this link not existing at all. Research on female sexual behavior has historically been sparse because of past beliefs that females are “passive recipients of male behavior,” she tells the publication.

Brindle says to WION that she finds it “absolutely baffling that nobody has researched such a common behavior across the animal kingdom.”

“For people who think masturbation is wrong, or unnatural in some way, this is perfectly natural behavior,” she tells the publication. “It’s part of our healthy repertoire of sexual behaviors.”

How Old Is Your Dog in Human Years?

Jul. 6th, 2020 10:23 am If there’s one myth that has persisted through the years without much evidence, it’s this: multiply your dog’s age by seven to calculate how old they are in “human years.” In other words, the old adage says, a four-year-old dog is similar in physiological age to a 28-year-old person.

If there’s one myth that has persisted through the years without much evidence, it’s this: multiply your dog’s age by seven to calculate how old they are in “human years.” In other words, the old adage says, a four-year-old dog is similar in physiological age to a 28-year-old person.But a new study by researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine throws that out the window. Instead, they created a formula that more accurately compares the ages of humans and dogs. The formula is based on the changing patterns of methyl groups in dog and human genomes — how many of these chemical tags and where they’re located — as they age. Since the two species don’t age at the same rate over their lifespans, it turns out it’s not a perfectly linear comparison, as the 1:7 years rule-of-thumb would suggest.

The new methylation-based formula, published July 2 in Cell Systems(https://www.cell.com/cell-systems/fulltext/S2405-4712%2820%2930203-9) , is the first that is transferrable across species. More than just a parlor trick, the researchers say it may provide a useful tool for veterinarians, and for evaluating anti-aging interventions.

“There are a lot of anti-aging products out there these days — with wildly varying degrees of scientific support,” said senior author Trey Ideker, PhD, professor at UC San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center. “But how do you know if a product will truly extend your life without waiting 40 years or so? What if you could instead measure your age-associated methylation patterns before, during and after the intervention to see if it’s doing anything?” Ideker led the study with first author Tina Wang, PhD, who was a graduate student in Ideker’s lab at the time.

The formula provides a new “epigenetic clock,” a method for determining the age of a cell, tissue or organism based on a readout of its epigenetics — chemical modifications like methylation, which influence which genes are “off” or “on” without altering the inherited genetic sequence itself.

Epigenetic changes provide scientists with clues to a genome’s age, Ideker said — much like wrinkles on a person’s face provide clues to their age.

Ideker and others have previously published epigenetic clocks for humans, but they are limited in that they may only be accurate for the specific individuals on whom the formulas were developed. They don’t translate to other species, perhaps not even to other people.

Ideker said it was Wang who first brought the dog idea to him.

“We always look at humans, but humans are kind of boring,” he said. “So she convinced me we should study dog aging in a comparative way.”

To do that, Ideker and Wang collaborated with dog genetics experts Danika Bannasch, DVM, PhD, professor of population health and reproduction at UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, and Elaine Ostrander, PhD, chief of the Cancer Genetics and Comparative Genomics Branch at the National Human Genome Research Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health. Bannasch provided blood samples from 105 Labrador retrievers. As the first to sequence the dog genome, Ostrander provided valuable input on analyzing it.

Dogs are an interesting animal to study, Ideker said. Given how closely they live with us, perhaps more than any other animal, a dog’s environmental and chemical exposures are very similar to humans, and they receive nearly the same levels of health care. It’s also important that we better understand their aging process, he said, as veterinarians frequently use the old 1:7 years ratio to determine a dog’s age and use that information to guide diagnostic and treatment decisions.

What emerged from the study is a graph that can be used to match up the age of your dog with the comparable human age. The comparison is not a 1:7 ratio over time. Especially when dogs are young, they age rapidly compared to humans. A one-year-old dog is similar to a 30-year-old human. A four-year-old dog is similar to a 52-year-old human. Then by seven years old, dog aging slows.

“This makes sense when you think about it — after all, a nine-month-old dog can have puppies, so we already knew that the 1:7 ratio wasn’t an accurate measure of age,” Ideker said.

According to Ideker, one limitation of the new epigenetic clock is that it was developed using a single breed of dog, and some dog breeds are known to live longer than others. More research will be needed, but since it’s accurate for humans and mice as well as Labrador retrievers, he predicts the clock will apply to all dog breeds.

Next, the researchers plan to test other dog breeds, determine if the results hold up using saliva samples, and test mouse models to see what happens to their epigenetic markers when you try to prolong their lives with a variety of interventions.

Meanwhile, Ideker, like many other dog owners, is looking at his own canine companion a little differently now.

“I have a six-year-old dog — she still runs with me, but I’m now realizing that she’s not as ‘young’ as I thought she was,” Ideker said.