Productivity or Exploitation?

Mar. 2nd, 2025 08:23 am Google co-founder Sergey Brin says the company could achieve Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) if employees worked harder and were in the office more. "Sixty hours a week is the sweet spot of productivity," he wrote in an internal memo.

Google co-founder Sergey Brin says the company could achieve Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) if employees worked harder and were in the office more. "Sixty hours a week is the sweet spot of productivity," he wrote in an internal memo.AGI is a type of AI that matches or even surpasses human cognitive abilities. It can understand and apply knowledge across a wide range of tasks like a human, rather than across a limited set of use cases. In the memo sent to employees working on Google's Gemini AI, Brin said: “Competition has accelerated immensely, and the final race to AGI is afoot.”

He added: “I think we have all the ingredients to win this race, but we are going to have to turbocharge our efforts.”

Brin singled out "a small number [of employees who] put in the bare minimum to get by." To him, that means they “work less than 60 hours," which is "not only unproductive but also highly demoralizing to everyone else."

Brin also recommended that employees trek to the office at least every weekday. Google’s official return-to-the-office policy mandates three days a week on-site.

Google’s AI staffers are apparently already familiar with brutal workloads. Google’s search boss, Prabhakar Raghavan, claimed that Gemini staff were at one point putting in 120 hours a week to fix a flaw in Google’s image-recognition tool.

In January, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said he's "now confident we know how to build AGI as we have traditionally understood it,” and that in the next few years, “everyone will see what we see.” That has required some technical staff to work 10-hour days six days a weeks.

Employees at Elon Musk's xAI have also disclosed 12-hour-plus working days. Musk himself has pegged the arrival of AGI at some point in 2026.

The jury is still out on whether AGI is a realistic short-term goal. Gary Marcus, professor emeritus of psychology and neural science at New York University, has critiqued the claims of tech CEOs like Altman, pointing out the numerous technical issues(More details: https://garymarcus.substack.com/p/sam-altman-thinks-that-agi-is-basically).

Friendships With Yours Boss

Sep. 23rd, 2023 08:23 am Spending time with people you like makes most things more appealing, including work. If a job is sufficiently humdrum, camaraderie among colleagues can be the main draw. The support of friends can also encourage people to try new things. A study from 2015 by Erica Field of Duke University, and her co-authors, looked at the impact of business training given to Indian women. Women who attended the course with a friend were more likely to end up taking out loans than those who came alone.

Spending time with people you like makes most things more appealing, including work. If a job is sufficiently humdrum, camaraderie among colleagues can be the main draw. The support of friends can also encourage people to try new things. A study from 2015 by Erica Field of Duke University, and her co-authors, looked at the impact of business training given to Indian women. Women who attended the course with a friend were more likely to end up taking out loans than those who came alone.The reverse also applies. Antagonistic relationships with co-workers are always likely to make working life miserable. A study conducted by Valerie Good of Grand Valley State University found that loneliness has an adverse effect on the performance of salespeople. Among other things, they start spending more on wining and dining their customers. The only thing worse than a salesperson who sees you as a way to make money is one who wants your company.

So friends matter. The problems come when managers see the words “higher employee engagement” and leap to the conclusion that they should try to engineer work friendships. In a report published last year Gallup gave the example of an unnamed organisation which has a weekly companywide meeting that spotlights one employee’s best friend at work. It’s not known if, in the q&a, others pop up to sob: “But I thought we were best friends at work.”

Startups also offer services to encourage work friendships. One monitors the depth of connections between people in different teams. It identifies shared interests (gluten-free baking, say, or workplace surveillance) between employees who don’t know each other and arranges meetings between them. You thought life was bad? At least you are not making crumpets with a stranger in finance.

It is a mistake for managers to wade into the business of friend-making, and not just because it royally misses the point. The defining characteristic of friendship is that it is voluntary. Employees are adults; they don’t need their managers to arrange play-dates. And the workplace throws people together, often under testing conditions: friendships will naturally follow.

The bigger problem is that workplace friendships are more double-edged than their advocates allow. They can quickly become messy when power dynamics change. The transition from friend to boss, or from friend to underling, is an inherently awkward one (“This is your final warning. Fancy a pint?”).

And friendships have the potential to look a lot like cronyism. A clever study by Zoe Cullen of Harvard Business School and Ricardo Perez-Truglia of University of California, Berkeley, found that employees’ social interactions with their managers could give their career prospects a boost relative to others.

The researchers looked at promotions of smokers and non-smokers who worked for a large bank in South-East Asia, hypothesising that sharing smoking breaks with managers who also indulged might give workers a leg up. And so it did. Smokers who moved from a non-smoking boss to a puffer were promoted more quickly than those who moved to another non-smoker. The authors found that social interactions did not just help smokers; socialising between male managers and male employees played a large role in perpetuating gender pay gaps. If firms are going to make friendship their business, they should worry about its downsides, too.

Bottom line is companies should facilitate interactions between employees, particularly in a world of hybrid and remote working. Social gatherings and buddy systems are reasonable ways to encourage colleagues to meet each other and to foster a culture. But a high-quality work relationship does not require friendship. It requires respect for each other’s competence, a level of trust and a desire to reach the same goal; it doesn’t need birthday cards and a shared interest in quiltmaking. Firms should do what they can to encourage these kinds of relationships. If individuals want to take it further, it’s entirely up to them.

Polywork - LinkedIn Challenger

Aug. 9th, 2021 10:00 amFor many, due to student loans, rising rent, and other bills, the side hustle is less a choice for extra money and more a necessity. Slightly different than a necessary hustle but still falling into these new lifestyles of Millennials and Gen Z is the concept of polywork: the rejection of traditional full-time jobs in favor of pursuing multiple jobs to fulfill multiple interests. Someone might work as a social media marketer while also being an investor, a writer, and a podcast host; they might also run a nonprofit, manage investments and field more creative roles such as producing plays.

This approach to work and life has spawned at least one platform expressly for advertising all of your various skills, known as Polywork(https://www.polywork.com), backed by such names as Ray Tonsing, YouTube co-founder Steve Chen, Twitch co-founder Kevin Lin, and Paypal co-founder Max Levchin. The site serves as a social-professional network, like LinkedIn, but one dedicated to showcases, professional portfolios or journals; they want to tell the full story of your career. The early adopters might be exactly whom you’d expect: influencers, developer advocates, designers, models, musicians, lifestyle entrepreneurs, etc. While it’s easier to conceive of those in creative fields or marketing or service roles pursuing multiple jobs at once, we often think of engineering roles as having the more traditional bounds of a full-time position. Given the demands of the work, is polywork possible as an engineer?

One of the longest-standing examples to examine is the freelance or contractor engineer. Often this is someone who joins teams and organizations on a project-by-project basis or for a set period of time. They may also be known as a consulting engineer, often an academic with specialized skills. This means that in order to take on work on the side of the main job with a university, an engineer will have invested a large amount of time and energy and will likely be later in their career. It is also true that a university will often OK consulting work as long as it brings some benefit back into the department; those with full-time industry jobs are far less likely to allow employees to take on work for possible competitors, often stipulating exclusivity in contracts.

Still, none of this quite approaches the idea of polywork, per se. This is about those with engineering skills using them in different areas of one industry or taking on work requiring their specialized skillset as it comes, enabling some more flexibility than a commitment to a single team. Polywork, on the other hand, describes the use of a breadth of skills to pursue many different fields of vocation. This comes at a time when people are not just overwhelmed by the stress of the pandemic but also often asked to wear many hats underneath a single job title, juggling administrative work with academia, or event planning with online marketing.

The platform Polywork conducted a study on their burgeoning workforce, finding that of the 1,000 workers it polled, aged 21 to 40 years old, 55% said an exciting professional life was more important than money, and just 35% said they could see themselves working a single job for life. Nearly 65% said they were already doing more than one job or hoped to, and even more believe that the pandemic has accelerated this trend, dovetailing with the fall in job satisfaction over the course of the pandemic. Polywork’s founders envision it as a shift in the workforce toward entrepreneurship.

Extrapolating this broader data to engineering, an industry less affected by the pandemic than many, may be difficult. Still, the younger members of the engineering workforce, like their Gen Z and Millennial counterparts in other industries, may be more likely to bulk at the prospect of the confines of the stable, single-faceted career. One of Polywork’s advisors is Idan Gazit, the director of research and future projects at GitHub, who says that people struggle with how one-dimensional job descriptions can be. Instead of being asked to “write code and more code,” he asks, “Where can you find people and opportunities to write code but also grow professionally, be given responsibility for outcomes?”

Engineers absolutely have skills that are pivotable. The trick is having the space and time to develop them and to imagine their uses outside of your field. And some do; there are mechanical engineers who are writers or chemical engineers who take public speaking engagements.

Polywork’s founder Peter Johnston makes the claim that as this desire for multi-faceted career develops and expands. Employers will have no choice but to accommodate it. “If businesses do not listen to their talent, we will see those companies start to become dinosaurs,” he said in Digiday.

It may take time for businesses to adapt for polywork to be truly possible for the average engineer, but if truly driven by the entrepreneurial spirit, engineers might well make the push. It is already possible to see hobbyists producing projects found on platforms like GitHub, spinning their interests outside of whatever their work may be into projects that are shared with the community and beyond. These projects encompass the desire for multi-faceted work lives and for filling needs in sectors, industries, and the everyday that are not necessarily part of their standard workday.

Polywork is an acknowledgment of the desire to expand beyond what someone else is asking of you, one certainly present in a community that thrives on sharing knowledge and finding solutions. As labor practices continue to evolve, it is certainly possible for more engineers to find the freedom to pursue other interests.

Office Politics

Aug. 4th, 2021 04:44 pm We used to make things. Now we have meetings. On any given weekday some 50m meetings are held in American workplaces alone. The average executive now spends 23 hours in them each week, a figure that has more than doubled since the 1960s. The number of meetings proliferated in the 1980s as Western economies moved away from manufacturing towards “knowledge” industries that seemed to require a lot of talking. And while covid-19 may have shut down the office (at least temporarily), it magnified the importance of meetings, which now take place on our laptops. During the pandemic we’ve spent more time in them than we ever did in person.

We used to make things. Now we have meetings. On any given weekday some 50m meetings are held in American workplaces alone. The average executive now spends 23 hours in them each week, a figure that has more than doubled since the 1960s. The number of meetings proliferated in the 1980s as Western economies moved away from manufacturing towards “knowledge” industries that seemed to require a lot of talking. And while covid-19 may have shut down the office (at least temporarily), it magnified the importance of meetings, which now take place on our laptops. During the pandemic we’ve spent more time in them than we ever did in person.Despite their centrality to modern life, few of us have a good word to say about meetings. Surveys suggest we consider at least half the ones we attend to be ineffective – the same bores drone on, the people with something useful to say don’t speak and nothing of importance gets decided. In many office cultures, a meeting is a byword for a tedious, time-wasting exercise.

Frustration with meetings has fuelled a mini-industry in management books – “How to Hold Successful Meetings”, “Meeting Design” and “Death by Meeting: A Leadership Fable” – dedicated to solving what one author labels “the most painful problem in business”.

Yet perhaps the sharpest analysis lies elsewhere. Though office meetings are a relatively recent phenomenon, people have been gathering to discuss decisions since Adam and Eve huddled over the forbidden fruit, and successive generations of poets and writers have chronicled the dynamics in their work.

“The Iliad”, Western literature’s foundational text, kicks off with a meeting. The Greeks are nine years into the siege of Troy, a plague has ravaged their ranks and they gather to ponder the flagging campaign (good teamwork is conspicuously absent: Achilles, the Greek’s foremost warrior, comes close to killing the commander, King Agamemnon).

In detailing the twists and turns of this conference, and subsequent ones held by the Greeks, Trojans and gods of Mount Olympus, Homer nails meeting behaviour with a precision that management gurus today can only dream of. Where Homer blazes a trail, other literary greats follow: the Western canon is ripe with unharvested wisdom on how to make meetings more productive. Time to put yourself on mute, turn off your camera and get reading.

Though “The Iliad” is ostensibly a book about bloody battles and an interminable siege, much of the action turns on arguments between key individuals. A little way into the epic, the assembled Greeks are once again holding a discussion on what to do about their stalemate (in fact Agamemnon has already resolved to have another crack at the walls of Troy). A commoner, Thersites, speaks up to make the case for cutting their losses: their ships are rotting, they already have plenty of loot and Agamemnon has already proved to be a poor leader. Isn’t it time to head home?

Odysseus, a high-ranking commander, orders Thersites to check his “glib tongue” and then beats him up for “playing the fool” and daring to “argue with princes”; the crowd delights at Thersites’s humiliation.

By inviting us to watch a reasonable argument dismissed with violence, Homer makes clear that the Greeks did not believe in a frank exchange of views. The meeting was a large one, but common folk were there to legitimise decisions already taken by their superiors. Such assemblies were clearly as frustratingly common in Homer’s time as they are in ours.

Encouraging junior staff to voice their opinions is one of the biggest difficulties modern managers face. Many, like Homer’s warlords, shut them down – truly open meetings are a nightmare to run. But getting the view from the floor isn’t just good for employees’ morale; it’s a way to gather useful information and different opinions. Any organisation that shuts down its Thersites is losing valuable insights. The Greeks took Troy in the end, but Thersites was right about the state of their navy: Odysseus, famously, got shipwrecked on the way home.

Bosses typically get to be bosses because they are confident in their own judgment and willing to assert themselves. That often means they become furious when they’re challenged – which makes it hard to step back and hold an open discussion.

Few works of literature dramatise this problem better than “King Lear”. Like “The Iliad”, the play opens with a meeting, as Lear discusses how to manage his succession. As with many managers, he has already predetermined the course of action: he plans to divvy up his kingdom between his three daughters. His only decision is how large a share to give each child, a judgment he will make depending on their answer to the question, who “doth love us most”. The real purpose of the meeting, it becomes clear, is for the old king to be lavished with “opulent” praise.

His two older children strive to outdo each other with performative sycophancy (no other joy, apparently, is as great as their love for their father). But Cordelia, his youngest – and the only one who genuinely loves her father, as the play goes on to demonstrate – refuses to flatter him (“I cannot heave my heart into my mouth”). Rather than hear her out, Lear flies into a rage, strips her of her portion and disowns her.

The snap decision testifies to Lear’s poor management skills. What comes next is even more of a no-no. Kent, the king’s most loyal aide, steps in to ask his master to reconsider his punishment of Cordelia. Lear silences him, warning, “Come not between the dragon and his wrath.” Kent insists on speaking his mind, saying he is duty bound to be “unmannerly when Lear is mad”. The king sends him into exile.

The figure of the overbearing leader who pays the price for his failure to countenance “the moody frontier of a servant brow” recurs throughout Shakespeare’s histories and tragedies. In “Henry IV, Part I”, the rebel Hotspur is so unwilling to listen to counsel that his ally Northumberland blasts him for “tying thine ear to no tongue but thine own!” In “Richard III” the king turns on Buckingham, his partner in crime, the moment that he expresses faint doubts about Richard’s schemes. Similarly, bosses who expect their underlings merely to back up their views – and leave them too frightened to contradict them – often make bad decisions.

Nowadays, leaders are better at pretending to listen to their subordinates. But fear of displeasing the boss still shapes most meetings. During the Cuban missile crisis, John F. Kennedy was so concerned that his national-security staff would rather say the right thing in front of him than work out the best strategy that he left the room for many discussions.

Today’s chief executives tend to follow King Lear, not Kennedy. According to one study, the person running a meeting generally speaks for between a third and two-thirds of the time allotted to the session. As the authors of this survey noted: “Even in egalitarian Denmark, we very rarely observed meeting participants challenge their leaders’ right to speak as much as they please.” King Lear created a “stage of fools”. Try not to do the same.

Anyone who thinks keeping a group discussion on track is easy would do well to study “Lord of the Flies”. William Golding’s novel follows a bunch of schoolboys stranded on a desert island after a plane crash. Meetings become central to their attempt to structure their mini-society, and they adopt a rule that anyone can speak if they’re holding the group’s conch shell (a prefiguration of Zoom’s yellow halo).

They clearly believe that more voices would improve the group’s decisions. It is a great, democratic experiment. But it fails.

Ralph, the boys’ putative leader, finds it impossible to translate talk into action, and laments the frequency of meetings at which nothing is achieved. “Everybody enjoys speaking and being together. We decide things. But they don’t get done.” His words will resonate with many modern managers.

The inability to manage discussion also results in a two-tier system. As Ralph observes, “practised debaters – Jack, Maurice, Piggy – would use their whole art to twist the meeting.” This leads to less adept speakers becoming marginalised. As Jack puts it: “It’s time some people knew they’ve got to keep quiet and leave deciding things to the rest of us.”

We have all experienced the situation whereby a few individuals dominate – and people who talk first and frequently in meetings tend to have an inordinate impact on the flow of discussion. Individuals who love the sound of their own voice are not necessarily well liked by others in the group, but we generally listen to them: people tend to think of them as influential by default. And talkativeness feeds on itself. Studies show that the more someone contributes in a meeting, the more they are likely to be asked questions. We seem to assume that people speak because they have something useful to say. So it was with Golding’s tribe on the island.

The problem with letting meetings run wild isn’t just that quieter (and less white and less male) voices are marginalised. Counterintuitively, you’re not as likely to learn anything new. Garold Stasser, a social psychologist, has shown that when there are no rules to meetings, conversations tend to be a rehash of what everyone already knows. Meetings without order don’t achieve anything except the entrenchment of powerful personalities, as Piggy learned the hard way. You can’t save a civilisation – or bring light to the darkness of man’s heart – with a conch shell alone.

At the start of “Paradise Lost” Satan and his army of fallen angels convene, much like Homer’s Greeks, in order to work out how to turn their fortunes around. Satan has just led the infernal rabble in a spectacularly botched rebellion in Heaven and now they’re literally stuck in Hell.

Unlike Agamemnon, Satan seems genuinely keen to come up with a strategy that everyone supports (not for nothing was John Milton an advocate of the parliamentarians in England’s civil war).

When Satan opens the floor to debate, four arch-demons make their case. Moloch advocates “open Warr”. Belial, whom Milton describes as an artful and cynical speaker, suggests that they do nothing and hope God sees fit to forgive them. Mammon argues for abandoning any idea of returning to Heaven and instead building an empire in Hell. And Beelzebub counsels sending a demon to Earth to seduce or destroy this “new Race call’d Man”. The issue is put to a vote.

This emphasis on collective decision making characterised many literary meetings after Homer. Influenced by the ideals of Athenian democracy, playwrights such as Aesychlus and Euripides depicted meetings in which the outcome was decided by the mood in the room, not the most senior person there. The result wasn’t always the right one, but the procedure was represented as admirable.

In Hell, the diabolical assembly chose to precipitate the fall of Man – which turns out to be the option Satan was most in favour of all along. Some scholars have suggested that Satan manipulated the vote. But perhaps they don’t want to acknowledge that, in getting people to vote for his preferred outcome, Satan was simply really good at meetings.

Management by plebiscite is not, of course, a viable option for most companies. But Satan knew what he was doing. It’s a good idea to ask everyone in the room to register their opinion at the end of the session, even if you don’t have a yes-no question – you can ask people how likely they think an outcome is, or to rank the various options presented. As well as giving people a sense that their voice matters, consulting a wider group gives leaders access to a collective judgment that – as a large body of literature on the wisdom of crowds shows – is likely to be a good one.

Deep in the laws and commentaries of the Talmud, there is an unusual provision about capital punishment: if all 71 judges in a capital case agree that the death penalty should be imposed, then it is automatically taken off the table.

This seems counterintuitive, given that courts today often insist on unanimity to convict someone of murder. But the Talmudic principle embodies an important insight about the perils of consensus: if everyone is seeing things a certain way, you may well have missed something important.

When you look back at famously bad decisions made by small groups – the launch of the Challenger space shuttle, Enron’s board of directors signing off on risky accounting practices – it’s striking how sure participants were that they were right, and how little disagreement was voiced.

Arthur Schlesinger, an adviser to Kennedy, noted that in the discussions that led up to the Bay of Pigs disaster in 1961, meetings “took place in a curious atmosphere of assumed consensus”. Information that might have disrupted that accord was excluded or rationalised away. The longer people talked to each other, the dumber they became. Meetings didn’t open minds, it closed them.

You sometimes need an active strategy to avoid groupthink, which arises from a toxic but beguiling combination of conformism and positive reinforcement. When the judges of the Sanhedrin, the supreme Jewish court in Temple times, passed their verdicts, they would speak in reverse order of seniority, so that less experienced judges wouldn’t tailor their opinions to fit those of senior ones.

More recent management experts like Kathleen Eisenhardt and Jay Bourgeois actively encourage a “good fight” in meetings. Arguments can be a sign that participants fundamentally trust each other and are working towards the same goal – that’s what allows them to express substantive differences of opinion.

It takes a rare leader to see discord as a boon, however. Alfred Sloan, the legendary boss of General Motors from the 1920s to the 1950s, was one such maverick. “Gentlemen, I take it we are all in complete agreement on the decision here,” he said at the end of one board meeting. “I propose we postpone further discussion of this matter until our next meeting, to give ourselves time to develop disagreement and perhaps gain understanding of what the decision is all about.” Agamemnon would probably have had him thrashed.

Tech Pros Depression

Dec. 7th, 2018 10:12 am A new study shows that, in tech, over one-third of professionals admit they have issues with depression. Specifically, 38.8 percent of tech pros responding to a Blind survey say they’re depressed. When you tie employers into this, the main offenders are Amazon and Microsoft, where 43.4 percent and 41.58 percent (respectively) of employees say they’re depressed. Intel rounds out the top three with 38.86 percent of its respondents reporting issues with depression.

A new study shows that, in tech, over one-third of professionals admit they have issues with depression. Specifically, 38.8 percent of tech pros responding to a Blind survey say they’re depressed. When you tie employers into this, the main offenders are Amazon and Microsoft, where 43.4 percent and 41.58 percent (respectively) of employees say they’re depressed. Intel rounds out the top three with 38.86 percent of its respondents reporting issues with depression.I’ll point out the top three companies may not be entirely to blame for the depression concerns of tech pros. All three have large footprints in the Pacific Northwest, where the shorter daylight of Fall and Winter contribute to Seasonal Affective Disorder, or SAD. This narrow window of daylight, along with routine overcast or rainy conditions, can throw off a body’s circadian rhythm. Seattle psychiatrist David Avery tells The Seattle Times that less daylight can also affect the brain’s hypothalamus, which directs the body’s release of hormones such as melatonin and cortisol. (It’s worth noting Blind didn’t identify any geographical data about respondents to its depression survey.)

There are similarities between this depression survey and other Blind studies. Over one-third of tech pros report being depressed; over half say their workplace is unhealthy; nearly 60 percent report burnout. An anonymous Dice survey shows most tech pros are dissatisfied with their job enough to consider seeking new employment elsewhere. In other words, across the industry, there’s a strong sense of dissatisfaction amongst tech pros.

At least when it comes to users, tech companies seem to realize their products have an impact on mental health. At WWDC 2018, Apple introduced App Limits, a method to reduce how often you use your phone, particularly the apps on it; it seems to focus in particular on social media, which has been proven many times to directly link to depression.

The upside to this survey is that most tech pros aren’t reporting depression issues. While that’s wonderful, we can’t overlook the nearly 40 percent of tech pros who admit feeling depressed. If you feel similarly, please reach out to a mental health professional for guidance and best practices to deal with your depression the right way.

More details: http://blog.teamblind.com/index.php/2018/12/03/39-percent-of-tech-workers-are-depressed

Age Discrimination

Sep. 21st, 2018 08:28 am IBM is the target of a new age-discrimination lawsuit filed on behalf of three employees.

IBM is the target of a new age-discrimination lawsuit filed on behalf of three employees.“Over the last several years, IBM has been in the process of systematically laying off older employees in order to build a younger workforce,” those employees insisted in the suit, which was filed by Shannon Liss-Riordan, an attorney known for suing Uber, Amazon, and other tech giants.

Nonetheless, the lawsuit comes at a sensitive time for IBM, which faces at least one other lawsuit related to the termination of older workers. Fueling the legal fire is a much-circulated report issued earlier this year by ProPublica and Mother Jones, which suggests that, over the past five years, IBM has eliminated more than 20,000 jobs held by American employees aged 40 and over, “about 60 percent of its estimated total U.S. job cuts.”

IBM isn’t the only tech giant facing age-discrimination action. As of May 2018, Intel was reportedly in the crosshairs of the EEOC over targeting older employees for dismissal. When the news of that investigation first broke, an Intel spokesperson insisted that any layoffs were “based solely upon skills sets and business needs.”

Even job postings risk discriminating against older workers. In May, a lawsuit filed by the Communications Workers of America claimed that Facebook is filtering job ads to a younger crowd, violating fair employment laws in the process. “When Facebook’s own algorithm disproportionately directs ads to younger workers at the exclusion of older workers, Facebook and the advertisers who are using Facebook as an agent to send their advertisements are engaging in disparate treatment,” read the lawsuit filing. (The ACLU later filed its own action.)

Ageism remains a huge problem in the tech industry in general. Some 68 percent of Baby Boomers said they’re discouraged from applying for jobs due to age. Around 40 percent of those who belong to Generation X felt ageism is affecting their ability to earn a living. And 29 percent said they’ve “experienced or witnessed” ageism in their current workplace or their most recent employer.

LONELINESS Is A Crowded Room

Jul. 26th, 2018 09:03 am“LONELINESS is a crowded room,” as Bryan Ferry of the band Roxy Music once warbled, adding that everyone was “all together, all alone”. The open-plan office might have been designed to make his point. That is not the rationale for the layout, of course. The supposed aim of open-plan offices is to ensure that workers will have more contact with their colleagues, and that the resulting collaboration will lead to greater productivity.

Ethan Bernstein and Stephen Turban, two Harvard Business School academics, set out to test this proposition*. The authors surveyed interactions between colleagues in two unnamed multinational companies which had switched to open-plan offices. They did so by recruiting workers to wear “sociometric” badges. These used infra-red sensors to detect when people were interacting, microphones to determine when they were speaking or listening to each other, another device to monitor their body movement and posture and a Bluetooth sensor to capture their location.

At the first company, the authors found that face-to-face interactions were more than three times higher in the old, cubicle-based office than in an open-plan space where employees have clear lines of sight to each other. In contrast, the number of e-mails people sent to each other increased by 56% when they switched to open-plan. In the second company, face-to-face interactions decreased by a third after the switch to open-plan, whereas e-mail traffic increased by between 22% and 50%.

Why did this shift occur? The authors suggest that employees value their privacy and find new ways to preserve it in an open-plan office. They shut themselves off by wearing large headphones to keep out the distractions caused by nearby colleagues. Indeed, those who champion open-plan offices seem to have forgotten the importance of being able to concentrate on your work.

Employees also find other ways of communicating with their fellow workers. Rather than have a chat in front of a large audience, employees simply send an e-mail; the result (as measured at one of the two companies surveyed) was that productivity declined.

Cubicles do not offer a great work environment either; they are still noisy and cut off employees from natural light. But at least workers have more of a chance to give their work area a personal touch. Allowing plenty of room for pictures of children, office plants, novelty coffee mugs—these are ways of making people feel more relaxed and happy in their jobs.

Such comforts are completely denied when companies shift to “hot-desking”, as 45% of multinationals plan by 2020, according to CBRE, a property firm, up from 30% of such companies now. Workers roam the building in search of a desk, like commuters hunting the last rush-hour seat or tourists looking for a poolside lounger. If you planned to spend a morning quietly reading a research paper or a management tome, tough luck; the last desk was nabbed by Jenkins in accounts.

Hot-desking is a clear message to low-level office workers that they are seen as disposable cogs in a machine. Combine this with the lack of privacy and the office becomes a depressing place to work. Workers could stay at home but that negates the intended benefits of collaboration that open-plan offices bring.

The drive for such offices is reminiscent of the British enthusiasm for residential tower blocks after the second world war. One British wartime survey found that 49% wanted to live in a small house with a garden; only 5% wanted a flat. But flats they got. Architects, who fancied themselves as visionaries like Howard Roark, the “hero” of Ayn Rand’s “The Fountainhead”, competed to create concrete temples for the masses to occupy. As David Kynaston, in his book “Austerity Britain” recounts, the desires of the actual residents were dismissed.

The real reason post-war architects built flats rather than homes is that it was a lot cheaper. And the same reason, not the supposed benefits of mingling with colleagues, is why open-plan offices are all the rage. More workers can be crammed into any given space.

Some people like them, of course, just as some like living in tower blocks. The only option for everyone else is to kick up a stink until executives change their minds and provide some personal space. In other words: workers of the world, unite. So you can separate again.

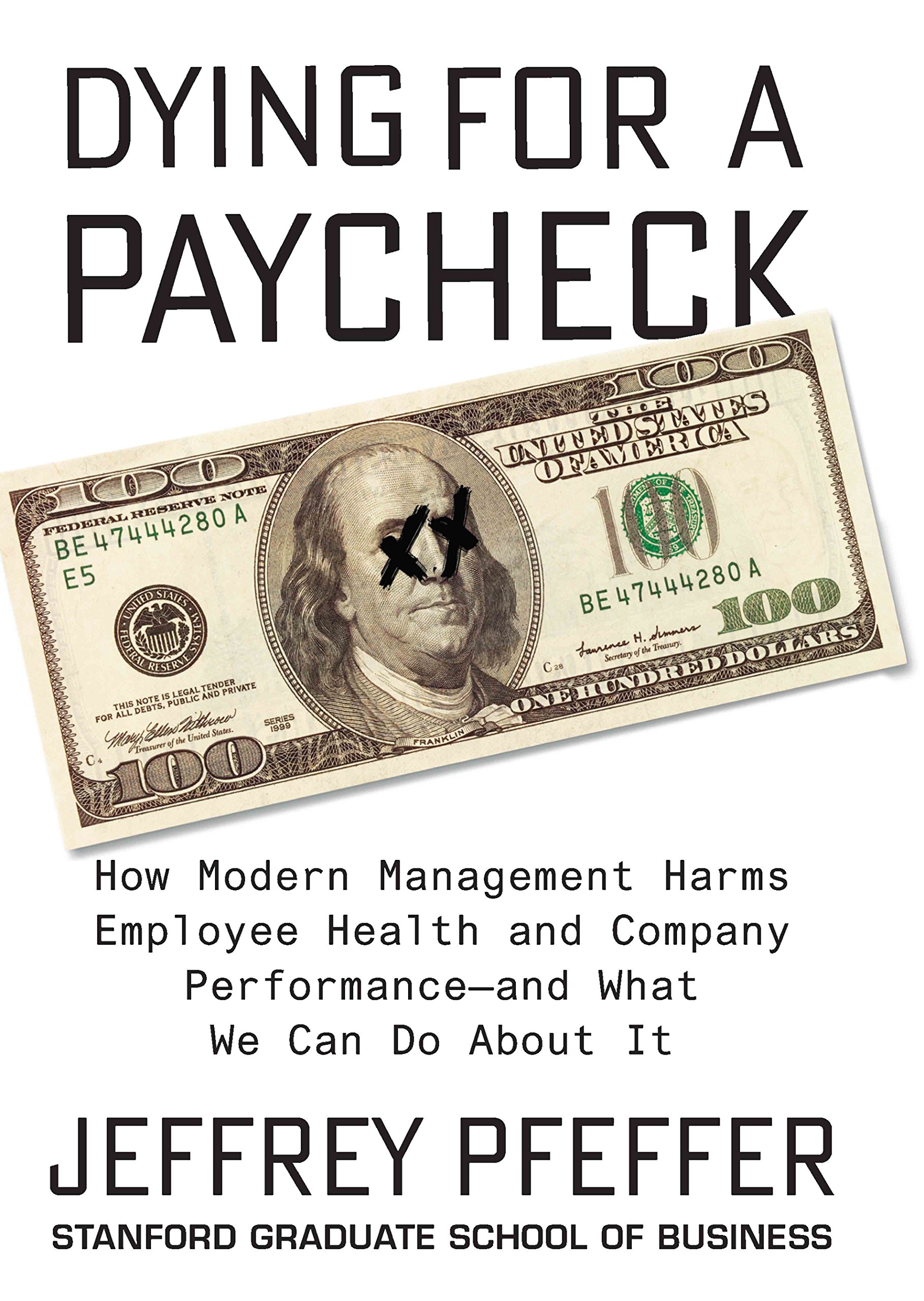

On Wednesday, September 12, 2001, no planes were flying in the United States. On the day after two planes flew into the World Trade Center and one crashed in Pennsylvania, it was not clear when air travel would be permitted to resume nor was there any certainty as to what the operational and logistical conditions would be when flights resumed—what new security arrangements would be required and how they would work. As the United States was already beginning to experience the effects of a recession, it was certainly unclear as to what the level of ongoing demand for air travel would be. In the days following September 11, US airlines such as American, Delta, and United did what they had done so many times before—laid off employees, about eighty thousand in total. All the big airlines announced layoffs almost immediately after September 11. That is, all except one.

On Wednesday, September 12, 2001, no planes were flying in the United States. On the day after two planes flew into the World Trade Center and one crashed in Pennsylvania, it was not clear when air travel would be permitted to resume nor was there any certainty as to what the operational and logistical conditions would be when flights resumed—what new security arrangements would be required and how they would work. As the United States was already beginning to experience the effects of a recession, it was certainly unclear as to what the level of ongoing demand for air travel would be. In the days following September 11, US airlines such as American, Delta, and United did what they had done so many times before—laid off employees, about eighty thousand in total. All the big airlines announced layoffs almost immediately after September 11. That is, all except one.Southwest Airlines sent an email to its employees and in that message noted that in its entire history it had never had a layoff or furlough. Although it could not promise that it would never have to lay people off, the airline made clear that it was committed to its people. Get back to work and provide great service to the customers when that became possible again, and the company would do its best to ensure the wellbeing of both its people and its patrons.

Southwest, even as it offered its customers no-questions-asked refunds if they wanted them, maintained its flight schedule and made a scheduled $179 million contribution to its employee profit-sharing plan in the aftermath of September 11. By the end of 2001, Southwest had not only made money for the year, it had been profitable even in the fourth quarter and had gained market share on its domestic US airline competitors. Going into 2002, the company had a market capitalisation greater than the entire rest of the US airline industry combined.

The idea that all companies, particularly those operating in cyclical industries, must resort to layoffs as a routine part of how they do business is simply not true. For a long time Xilinx, a semiconductor manufacturer, avoided the cycles of layoffs and rehiring so common to that industry. In the tech recession of 2001 and 2002, when Intel and Advanced Micro Devices cut nine thousand jobs, Xilinx laid off none of its 2,600 people. Toyota assiduously tries to avoid layoffs, even during times when the motor vehicle market is not doing well. Toyota has sought to retain employees on the payroll not just in Japan but in the company’s US factories as well.

Arc welding manufacturer Lincoln Electric, headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio, has survived two world wars and numerous economic cycles without sacrificing its employees or their jobs. The company is famous for its profit-sharing incentive plan that produces variable compensation costs and helps Lincoln avoid layoffs. Because pay declines when profits go down during recessions, Lincoln Electric can eschew layoffs as its wage costs decrease. One of Lincoln’s former CEOs described downsizing as “dumbsizing.” And a more recent CEO, a longtime veteran of the company, noted, “I think my philosophy and that of my predecessors is that we can perform in an economically challenging environment, and we can spread that pain in a way that long-term will better represent our shareholders’ interests without crucifying our employee base.”

SAS Institute, the largest privately owned software company in the world with 2016 sales of more than $3.2 billion, used the technology downturn in the early 2000s to hire hundreds of people and thereby gain both talent and market position. When the next economic recession hit in 2007 to 2008, Jim Goodnight, the CEO, noted that employees were frequently asking him if there were going to be layoffs. He sent out an email encouraging people to watch expenses but assuring them that there would be no economy-related layoffs. As he told me, although sales did not grow as fast during the recession as they had in the past—no surprise there—profitability was reasonably good. With people assured of their jobs and their security, they could focus on their work and be more productive, and, because they were grateful to be working for a compassionate employer, they reciprocated with diligence and creativity—and with enhanced attention to keeping expenses in check.

Layoffs reflect company values. Large grocery chain Whole Foods Market went through the economic crisis of the late 2000s laying off fewer than one hundred people. Chip Conley, the founder and leader of Joie de Vivre Hospitality, one of the largest boutique hotel chains in the United States, tried to minimise layoffs even as the company’s revenues fell more than 30 percent in the recession of the late 2000s. And having gone through that wrenching experience, when the economy recovered, Conley sold his stake in the hotel chain in part, he commented, so he would not have to go through the experience of laying off so many people again.

Some industrialised countries have adopted public policies that encourage employers to retain their workers. In many European countries, companies that lay off permanent staff are required to make large severance payments, thereby causing companies to have to balance the presumed savings from letting people go against these severance costs. Other policies require advance notice of layoffs and, in some instances, consultation with unions or workers’ counsels. Although such policies are presumed to create inflexible labor markets that result in persistently higher unemployment and less growth in employment, the evidence on such effects is mixed. Moreover, virtually no studies of labor market effects balance the costs of higher economic security against the benefits in health and well-being.

Germany, recognising that when people lose their jobs they collect unemployment benefits and other social-support payments, has experimented with offering companies some fraction of these anticipated payments to induce them to retain workers, even on a part-time basis. The German policies have often been credited with reducing the extent of economic dislocation that would otherwise occur during recessions. The point is that public policy is an important factor affecting company decisions about layoffs. Moreover, the cost of layoffs needs to be considered in deciding about the benefits and costs of policies that seek to reduce economic insecurity and layoffs.

Behaving Badly in 2017

Jan. 3rd, 2018 12:01 pm 2017 was a year with a lot of bad behavior going on. People were randomly clicking, other people where hacking, others were mistreating the disadvantaged. Perhaps more dismaying was the constant string of stories about the age discrimination and the mistreatment of women and minorities in technology.

2017 was a year with a lot of bad behavior going on. People were randomly clicking, other people where hacking, others were mistreating the disadvantaged. Perhaps more dismaying was the constant string of stories about the age discrimination and the mistreatment of women and minorities in technology.The corporate misogyny at Uber is perhaps the best example of horrifyingly bad behavior in tech companies, but it’s far from the only one. The multi-page manifesto written by a former Google engineer presenting reasons why women can’t succeed in the technology industry is another. But the fact is the “bro” culture in Silicon Valley and elsewhere in tech robs their businesses and all of society of the talent and productive potential of half the population.

Facebook is known for being one of the best places in the world to work, receiving annual accolades about its perks and benefits. But two new lawsuits are arguing that the social media giant is not an inclusive, great place to work if you’re above a certain age. 61-year-old Stephen Cohen, who lives in Manhattan, says he was approached by Facebook’s vice president of global marketing and director of sales and marketing staff about a job in communications. But when he sent them his resume, which listed his graduation date as 1978, they suddenly told him the position had been filled, according to the lawsuit filed in Manhattan federal court. This is the second age discrimination lawsuit to be filed against Facebook in recent days. According to City News Service, former Facebook employee Gary Glouner, 52, filed a suit in Los Angeles Superior Court alleging that he was fired in 2015 over his age and disability. Glouner claims that Facebook, whose motto was once “move fast and break things,” discriminated against older employees, including himself, for “not moving fast enough.” Glouner said he witnessed several other older employees get fired after being told that they were a “poor cultural fit,” or that they “didn’t get it” or that they “didn’t move fast enough,” according to the suit. Both lawsuits reference Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s speech to a tech gathering in 2007 as an examples of Facebook’s ageist culture. Back then, Zuckerberg was a 22-year-old unpolished Facebook CEO. In a Y Combinator speech, he made his generational preferences clear. “Young people are just smarter,” he said. “I want to stress the importance of being young and technical….Why are most chess masters under 30?…I don’t know…Young people just have simpler lives. We may not own a car. We may not have family.” Those words may come back to haunt Zuckerberg.

In October that an estimated 400 to 700 Tesla employees were dismissed, many of whom said the dismissals came with little or no warning. Tesla told that these cuts were made following the company’s annual performance review process. The United Auto Workers filed a complaint against Tesla on Oct. 25 2017, claiming the company fired workers who were trying to unionize. Also, Tesla said 17% of its employees were promoted, and almost half of those promotions were within its factory in Fremont. A quick look at Tesla’s career page shows a different, yet related problem: lots of job openings. It’s an issue the Musk later addressed in the earnings call, noting that the company is “sucking the labor pool dry” to fill positions at its factory in Fremont, Calif., and battery factory near Reno, Nevada. Tesla reported that it lost $619 million in the third quarter, its biggest-ever quarterly loss. Those losses were bigger than usual as Tesla tried to speed up production of its more affordable Model 3 sedan.

What the culture in these companies does is no better than the discrimination that takes place in many levels of society because of a person’s age, skin color or their place of origin. Sadly, because nobody wants to mess with the cool guys in tech, the theoretically progressive governments in California and elsewhere are slow to enforce discrimination laws.

When 2017 is remembered in the technology industry, it will be known as much for a general failure to invest in people. If a general realization began to grow in 2018 that money does not forgive evil. Despite the fact that some Silicon Valley companies, such as Uber, have grown rich mostly on venture funding, that does not give them license to abuse and repress employees in quest of a blockbuster initial public stock offering with a get-rich-at-all-costs mentality that beggars the usual corporate objectives of giving customers a good service at a fair price and employees a decent place to work.

Margaret C. Whitman. the board chairman and chief executive officer of HP revealed that she will be stepping away in February from the lightning-rod job she has had for the last six-plus years. She will be replaced by 23-year HP veteran Antonio Fabio Neri, the current president of HPE.

HPE's stock has risen from $9.88 on its first day, Nov. 1, 2015, to $13.95 on Nov. 30, 2017. HP Inc.'s has fared even better; on Dec. 3 2012, it was $5.90; it was $21.45 on Nov. 30, 2017. Investors should have no complaints, but critics say Whitman raised the value of the stock by cutting costs at HP, and they have a point. But the company has been managed by her and her team to stay in the financial black while revenues have leveled off and declined--mostly due to competition from smaller, more nimble new-gen software and hardware companies.

In her six-year tenure, Whitman had to do what managers universally hate to do: oversee the layoffs of employees. At last count, the number of those let go amounted to nearly 85,000. HPE and HP Inc. together still employ about 250,000 people worldwide. Eighty-five thousand! That's more than too much displacement for anybody to have to handle. Firing even one person is difficult.

Whitman's tenure at Hewlett-Packard was marked by a major split, a big spinout-merger, numerous acquisitions and several division sales that changed the legendary 78-year-old Silicon Valley company forever. The company was forced to evolve all through the first decade of the 2000s, when it made a $25 billion acquisition of Compaq in 2002 under then-CEO Carly Fiorina and a subsequent $11 billion acquisition of British analytics firm Autonomy that turned out to be a huge mistake. HP spent billions acquiring some promising companies during Whitman's time on the board and as CEO. They include 3COM (networking, 2010), 3PAR (data storage, 2010), Vertica (database analytics, 2011), Eucalyptus (cloud management software, 2014), Aruba Networks (mobile networking, 2015), Simplivity (hyperconverged data center equipment, 2017), Cloud Cruiser (cloud cost management and optimization, 2017) and Nimble Storage (flash and hybrid data storage, 2017). The spinout-merger of HPE's software business into Micro Focus, which became official Sept. 1, was another major milestone in Whitman's time at the helm.

The Autonomy deal was not a high point. It made under short-term CEO Léo Apotheker, who came from SAP and turned out to be ill-suited for the job. He lasted less than one year (2010-2011) before being replaced by Whitman. At the time, HP had fired its previous CEO (Mark Hurd, now at Oracle) for expenses irregularities, and appointed Apotheker as CEO and president. At the time, HP was seen as problematic by the market, with margins falling and having failed to redirect and establish itself in major new markets, such as cloud and mobile services. Apotheker's strategy was to dispose of hardware businesses like Palm and move into the more profitable software services sector, a strategy competitor IBM was also enacting at the time. As part of this strategy, Autonomy and its analytics franchise was acquired by HP in October 2011. HP paid $10.3 billion for 87.3 percent of the shares, valuing Autonomy at around $11.7 billion (£7.4 billion) overall, a premium of around 79 percent over market price. The deal was widely criticized as chaotic attempt to rapidly reposition HP and enhance earnings, and had been objected to even by HP's own CFO. Other problems eventually surfaced surrounding Autonomy, including allegations that it oversold its capabilities to Apotheker and other HP executives. After Apotheker was fired in September 2011, HP had to write off $8.8 billion of Autonomy's value. Litigation surrounding the ill-fated deal continues to this day. This is the unsettled scenario in which Whitman arrived in the CEO chair, although as a board member she certainly had to see some of the problems coming. Repercussions of these problems are still being felt today.

The 61-year-old Whitman, listed by Forbes as having $3 billion in assets, is stepping away from a hot-seat job that earns her about $20 million per year ($4.86 million of that in salary). She has served CEO tenures at both eBay (1998 to 2008) and HP (2011 to 2018), taking some time off from business in 2009 and 2010 in an unsuccessful run as a Republican for governor of California. In fiscal 2016, after the company split into two--HP Inc. and HP Enterprise, in 2015--she earned a cool $35.6 million, which included stock options worth $11.7 million alongside restricted shares worth $19 million if she meets certain performance requirements. Whitman, who will remain on the HPE board, has planned ahead, downsizing from her large Atherton estate to an apartment in Palo Alto, Calif. and a mountain home in Telluride, Colo.

Women in Google?

Sep. 19th, 2017 08:53 am

In August, 2017 Google fired a software engineer(James Damore) who wrote an internal memo that questioned the company’s diversity efforts and argued that the low number of women in technical positions was a result of biological differences instead of discrimination.

Just in September, 2017 a lawsuit filed by three former employees claims Google is systematically and knowingly paying women employees less than comparable male workers. Google says allegations are untrue.

The complaint, filed in the Superior Court of California in San Francisco Thursday, September 14, 2017 accused Google of systematically and knowingly paying women lower wages and compensating them less overall than male employees with substantially similar skills and experience.

The three ex employees who filed the lawsuit are: Kelly Ellis, who worked as a software engineer at Google between 2010 and 2014; Holly Pease who left Google in 2016 as a senior manager of business system integration; and Kelli Wisuri, a brand evangelist for the company between 2012 and 2015.

In a statement, Google spokeswoman Gina Scigliano said the company is reviewing the lawsuit, but disagrees with its central allegations. "We work really hard to create a great workplace for everyone, and to give everyone the chance to thrive here," she noted.

After the initial review the Labor Department asked Google for more compensation data, this time dating back to 2014. The agency says it is trying to find out if the wage gap it discovered during its first analysis is part of a broader pattern of discrimination against women at Google.

Age-discrimination in the Google

Oct. 8th, 2007 02:22 pmReid was hired at the age of 52 in 2002 as the director of operations and director of engineering. In 2003, he was demoted, and in 2004 he was fired, when he was 54, according to the lawsuit.

In his lawsuit, filed in July 2004, Reid said he worked closely with Google founders Sergey Brin, then 28, and Larry Page, then 29, and that he was fired because he was not a "cultural fit" with the company. According to the lawsuit, Page, who was almost 31 at the time, made the decision to fire Reid.

...one of Reid's supervisors, Urs Hoelzle, who is 15 years younger than Reid, and others, told him his opinions and ideas were "obsolete" and "too old to matter." He was also told that he was "slow," "fuzzy," lethargic," "did not display a sense of urgency" and "lacked energy," according to court documents. Reid said he was also called, "an old man" and an "old fuddy-duddy" by his colleagues.

Reid, who has a doctorate in computer science, said he was given a positive review by Google's vice president of engineering, Wayne Rosing, who wrote Reid's only written evaluation. Rosing, who was 55 at the time, described Reid in the review as having "an extraordinarily broad range of knowledge concerning operations, engineering in general, and an aptitude and orientation toward operational and IT issues."

Details: http://www.computerworld.com/action/article.do?command=viewArticleBasic&articleId=9041081&source=NLT_MGT&nlid=23

In his lawsuit, filed in July 2004, Reid said he worked closely with Google founders Sergey Brin, then 28, and Larry Page, then 29, and that he was fired because he was not a "cultural fit" with the company. According to the lawsuit, Page, who was almost 31 at the time, made the decision to fire Reid.

...one of Reid's supervisors, Urs Hoelzle, who is 15 years younger than Reid, and others, told him his opinions and ideas were "obsolete" and "too old to matter." He was also told that he was "slow," "fuzzy," lethargic," "did not display a sense of urgency" and "lacked energy," according to court documents. Reid said he was also called, "an old man" and an "old fuddy-duddy" by his colleagues.

Reid, who has a doctorate in computer science, said he was given a positive review by Google's vice president of engineering, Wayne Rosing, who wrote Reid's only written evaluation. Rosing, who was 55 at the time, described Reid in the review as having "an extraordinarily broad range of knowledge concerning operations, engineering in general, and an aptitude and orientation toward operational and IT issues."

Details: http://www.computerworld.com/action/article.do?command=viewArticleBasic&articleId=9041081&source=NLT_MGT&nlid=23