Отець Агапій Гончаренко народився Андрієм Онуфрієвичем Гумницьким 19 (31) серпня 1832 року. Його батько Онуфрій був православним пастором у їхньому селі Кривень, Київської області, Україна. Як і його батько, мати Андрія, Євдокія, була гордою нащадкою давнього українського козацького роду — Богунів. У 1651 році, під час українсько-польської боротьби, полковник Іван Богун прийняв командування козацьким військом у битві під Берестечком, Україна, коли гетьмана Богдана Хмельницького викрали татари.

Отець Агапій Гончаренко народився Андрієм Онуфрієвичем Гумницьким 19 (31) серпня 1832 року. Його батько Онуфрій був православним пастором у їхньому селі Кривень, Київської області, Україна. Як і його батько, мати Андрія, Євдокія, була гордою нащадкою давнього українського козацького роду — Богунів. У 1651 році, під час українсько-польської боротьби, полковник Іван Богун прийняв командування козацьким військом у битві під Берестечком, Україна, коли гетьмана Богдана Хмельницького викрали татари.Дитина середнього класу, Гончаренко восени 1840 року вступив до бурси (інтернату для хлопчиків), а пізніше до Київської духовної семінарії. На початку свого життя він мав змогу на власні очі бачити страждання простих українських селян. «Під час відпусток я мав змогу бачити, як польська аристократія ставилася до наших православних і як їхні слуги б'ють дівчат батогами», – писав Гончаренко у своїх «Спогадах» (опублікованих у 1894 році Михайлом Павликом у Коломиї, Західна Україна (Галичина)).

Молодий Андрій намагався уникнути цієї неприємної сцени в селі. У 1853 році він закінчив Київську духовну семінарію і, одягнувши чернечий одяг, переїхав до Печерської лаври в Києві, щоб стати послушником. Саме тут він прийняв чернече ім'я «Ахапій». Ахапій був вражений, побачивши мирськість ченців. Їхнє життя різко контрастувало з бідністю та стражданнями сільських людей, з якими юний послушник стикався, виконуючи свої обов'язки помічника митрополита Київського Філарета.

12 липня 1857 року Гончаренко мав насичену подіями зустріч у Києві з князем Сергієм Трубецьким, політичним вигнанцем, який повернувся з країни після невдалого повстання декабристів 1825 року. Ця група повстанців, яка мала значну кількість послідовників серед офіцерського корпусу, мала на меті ліквідувати два стовпи Російської імперії — самодержавство та кріпацтво. Таємні товариства були створені як у Росії, так і в Україні в 1818 році. Ці змовники так і не розібралися з політичною проблемою, яку ставила Україна, але багато їхніх письменників висловлювали співчуття до героїчних традицій України, особливо до саги про козаків. Декабристський рух став каталізатором розвитку української політичної та культурної свідомості 19 століття. Його зустріч із Трубецьким надихнула Гончаренка продовжити справу декабристів.

Восени 1857 року Гончаренко опинився в Афінах, Греція. Священний Синод (керівний орган царської Російської православної церкви) рекомендував призначити архідиякона (ієродиякона) до Російської консульської церкви в Афінах. Митрополит Київський Філарет обрав на цю посаду свого молодого помічника. Ахапій швидко занурився в грецьку культуру та почав вивчати мову філософів. Перебуваючи в Афінах, він зв'язався з Олександром Герценом та Миколою Огарьовим — двома відомими російськими політичними емігрантами, які публікували антицарські матеріали в Лондоні. Живо згадуючи страждання та жорстоке поводження з селянами поблизу Києва, аморальність та пияцтво в монастирі, Гончаренко почав писати статті для цих лондонських видань, для «Колокола» (Дзвін).

Ополудні 2 лютого 1860 року київського архідиякона запросили приєднатися до Олександра Петровича Озерова, російського посла в Афінах, на вечерю на борту корабля «Русалка». Після посадки на це судно Гончаренку вручили папірець, у якому повідомлялося, що він заарештований і буде депортований до Росії. «Русалка» перевезла київського ченця до Константинополя, де його кинули до в'язниці разом зі «злодіями та п'яницями російського походження». За дванадцять днів, які знадобилися російському військовому кораблю, щоб дістатися до цього міста, друзі Гончаренка в Афінах зв'язалися зі своїми контактами в османській столиці.

16 лютого молодому ченцю допомогли втекти з в'язниці, і він негайно вирушив до Лондона, куди прибув 4 березня. Він пробув там близько вісімнадцяти місяців. Перебуваючи там, він зустрівся з Герценом, Огарьовим та італійським політичним емігрантом Джузеппе Мацціні. Гончаренко працював у Британському музеї класифікатором та нумізматом. Він продовжував писати для Герцена та працював друкарем у крамниці Людвіга Чернецького. Агапій добре заробляв за свою роботу. Йому вдалося фінансово допомогти численним російським біженцям, які стікалися до Лондона в роки політичної невизначеності за царя Олександра II.

Агапій продовжував писати статті для видання «Колокол». На початку 1861 року він почав використовувати псевдонім «Гончаренко», а згодом обрав псевдонім як прізвище. Наприкінці 1861 року київський чернець повернувся до Греції через Туреччину. У січні 1862 року він відвідав свого дядька, Дмитра Богуна, на Афоні. Пізніше того ж місяця, після подання прохання про висвячення там, його було висвячено на священика. З Греції отець Гончаренко вирушив до Єрусалиму. Коли російський консул у Святому Місті дізнався про його присутність, Агапію погрожували арештом та депортацією. Молодий священик мав рекомендаційний лист, наданий йому князем Іваном Гагаріним, російським римо-католиком. Це забезпечило йому захист Єрусалимського патріарха. За пропозицією Гагаріна український вигнанець деякий час викладав у єзуїтській школі в Ліванських горах. Зрештою він переїхав до Александрії, Єгипет, де знайшов притулок у англійця сера Семюеля Бейкера.

Отець Гончаренко відкрив невеликий магазин поблизу залізничного вокзалу Каїра. Саме тут він зазнав першого нападу на своє життя. Його грецький нападник зізнався, що його найняв російський консул, щоб «вмовити» священика покинути Александрію. Еллінські друзі Ахапія закликали його повернутися до Греції та подати заяву на отримання громадянства. Він так і зробив і отримав громадянство 6 червня 1863 року. Наступного року український емігрант подорожував грецькими островами та східними містами як перекладач для двох російських вчених, Ямонського та Перцова, які шукали слов'янські реліквії.

Гончаренко поступово дійшов висновку, що його народ може повною мірою реалізувати свій інтелектуальний та культурний потенціал за кордоном. Розмови з впливовими російськими політичними емігрантами в Лондоні переконали його, що йому слід емігрувати до Сан-Франциско, щоб відкрити російське видавництво. Молодий священик сподівався об'єднати слов'янський народ Тихоокеанського узбережжя Сполучених Штатів у сильну організацію. Він попрощався з Афінами 18 жовтня 1864 року. Корабель «Ярінгтон» перевіз його з Ізміра, Туреччина, до Бостона, штат Массачусетс. У Новий рік 1865 року український православний священик прибув до Америки.

Перша неофіційна служба Грецької православної церкви, яку провів в Америці отець Гончаренко 6 січня 1865 року, викликала інтерес місцевих членів цієї віри. У лютому цей український емігрант був гостем на вечері, яку влаштував єпископ Поттер з Трійці-каплиці в Нью-Йорку. На цьому зібранні він дізнався від присутніх духовенства, що минулого року православних капеланів, які супроводжували російський флот (командувачем якого, до речі, був український адмірал С. Лессовський), запросили відслужити літургію в єпископальних церквах цього міста. Російські священики відмовили, мотивуючи це тим, що православ'я забороняє їм служити в протестантських церквах. Вони сказали: «Ми не будемо мати справ з єретиками». Єпископ Поттер запропонував отцю Ахапію можливість відслужити літургію в церкві Святої Трійці, розташованій на 26-й вулиці в Нью-Йорку. 2 березня 1865 року український священик відслужив першу публічну православну службу в Новому Світі.

Гончаренку було тридцять два роки, коли він вперше привернув увагу двох американських газет, The New York Evening Post та The New York Times. The New York Evening Post (2 березня 1865 року) надрукувала довгий звіт про православну службу, що відбулася в каплиці Святої Трійці, характеризуючи її заголовком «Значна та політична церемонія». Газета «Нью-Йорк Таймс» (3 березня 1865 року) також присвятила кілька колонок огляду цієї Літургії та її значення для російсько-американських відносин. В одному абзаці було наведено цікавий опис українського священика-вигнанця.

«Російсько-грецький священнослужитель, преподобний Агапій Гончаренко, — приємний і гідний на вигляд священнослужитель приблизно п'ятдесяти років. Він росіянин за походженням і випускник церковної академії Санкт-Петербурга. Корабель «Олександр Невський», який близько дванадцяти місяців тому вирушив з цього міста до Афін, приніс звістку до грецької столиці, що в цій країні багато представників Православної Церкви не мають пастора, і він прибув, запропонувавши свої послуги, акредитований митрополитом Афінським та Священним Синодом Королівства Греції».

Можливо, п'ять років постійних подорожей Гончаренка та його густа борода робили його набагато старшим (50), ніж він насправді мав (32). Швидше за все, сам священнослужитель дещо змінив ці друковані деталі свого життя, щоб замаскувати свою присутність у Нью-Йорку від пильних очей царського уряду.

Невдовзі з київським священнослужителем зв'язався російський консул у Нью-Йорку, барон Роберт Остен Сакен, щоб навчити цього чиновника грецької мови. Минуле Гончаренка, що був у втечі, поки що залишалося прихованим. Гострий погляд двоголового орла (символу царської влади) невдовзі простежив невловимі обриси попередньої «злочинної» діяльності отця Агапія. Барона попросили заарештувати українського вигнанця. Консул відмовився ініціювати цю дію.

Гончаренко знову потрапив у заголовки газет 15 квітня 1865 року, проводячи православну службу в церкві Святого Павла в Новому Орлеані, штат Луїзіана. Він провів освячення цієї першої грецької православної церкви в Сполучених Штатах. Імперський уряд вжив рішучих заходів, щоб ізолювати його від грецьких друзів. 13 травня 1865 року грецького консула в Нью-Йорку, Кира Ботассі, відвідав російський посол, барон Едвард де Штекль. Росіяни погодилися виділити кошти на будівництво нової православної церкви в місті з пастором, отцем Ніколасом Б'єррінгом. Грекам було наказано розірвати зв'язки з отцем Агапієм, «ворогом Росії». Гончаренко був змушений шукати нову роботу. Американське біблійне товариство найняло його для перекладу Біблії арабською та церковнослов'янською мовами.

Завдяки знайомству з італійським революціонером Мадзіні, українець потрапив до будинку Джона Сітті у Філадельфії, чий дім був місцем зустрічей іммігрантів-італійських патріотів. 28 вересня 1865 року в Нью-Йорку Гончаренко одружився з Альбіною, дочкою пана Сітті. Альбіна Сітті стала супутницею українського емігранта на все життя і зробила важливий внесок у його видавничу роботу на узбережжі Тихого океану.

Царські шпигуни уважно спостерігали за життям київського вигнанця в Нью-Йорку. Займаючись перекладами Біблії, він ніколи не забував про свій попередній план відкрити видавництво на Західному узбережжі. 1867 рік остаточно переконав його здійснити свою мрію. Переговори про продаж Російської Америки Сполученим Штатам відбувалися взимку та навесні того ж року. 18 жовтня 1867 року російський прапор було востаннє приспущено в Сітці, Аляска. Починаючи з 1808 року, Сітка стала столицею Російської Америки.

Точний характер участі Гончаренка в купівлі Аляски залишається прихованим. Цілком ймовірно, що він зв'язався з державним секретарем Сьюардом десь у 1867 році. Перші американські публікації православного священика (1868) були започатковані на прохання Сьюарда. За чотирнадцять днів до відправлення росіян з Аляски отець Агапій та його дружина-вчителька сіли на пароплав «Америка» в Нью-Йорку та відпливли до Панамського перешийка. Він та Альбіна накопичили значну суму грошей — 2500 доларів. Під час подорожі на захід серед їхніх речей був друкарський верстат з кирилицею вартістю 1600 доларів.

Потяг перевіз їх п'ятдесят сім миль через Центральну Америку, а потім інший корабель 6 листопада доставив їх до Сан-Франциско.

Український вигнанець розглядав можливість заснування свого видавництва на Алясці, але боявся цензури з боку американської військової влади, яка там контролювала. Сан-Франциско, головний порт судноплавства та сполучення з Російською Америкою та з неї, пропонував більш підходяще місце. Будинок за адресою Маркет-стріт, 536, став домівкою для першої російсько-англійської газети, що видавалася у Сполучених Штатах, «The Alaska Herald» («Свобода»). Протягом наступних п'яти років друкарня отця Гончарека також була місцем збору колишніх жителів Аляски, а також біженців з Росії та Сибіру.

Про волшебную силу алого белья я узнал несколько лет назад. Сначала не поверил, думал стеб. Ну серьезно: не могут же взрослые люди, находясь в здравом уме и трезвой памяти, верить в то, что нижнее белье определенного цвета может принести им удачу и богатство. А самым невероятным мне показалось, что трусы должны висеть не абы где, а именно на люстре. Якобы именно там, и больше нигде, активируется их волшебная сила.

Про волшебную силу алого белья я узнал несколько лет назад. Сначала не поверил, думал стеб. Ну серьезно: не могут же взрослые люди, находясь в здравом уме и трезвой памяти, верить в то, что нижнее белье определенного цвета может принести им удачу и богатство. А самым невероятным мне показалось, что трусы должны висеть не абы где, а именно на люстре. Якобы именно там, и больше нигде, активируется их волшебная сила.Кто придумал этот странный обычай, почему именно трусы, а не носки, люстра, а не книжная полка или кактус, история умалчивает.

Как водится, интернет предлагает несколько вариантов возникновения мифа. Пересказывать их здесь я не буду: легенда имеет самое широкое толкование — от древних или современных китайцев до каких-то супругов-психологов, придумавших «юмористическую школу волшебства» с целью высвободить позитивную и креативную энергию человека путем совершения разных абсурдных действий вроде закидывания белья на люстру.

Но это я уже сейчас все знаю, а тогда — ну поржали и забыли, как говорится. Мы же все уже большие девочки и мальчики, нас всякими глупостями не заманишь.

Несколько лет назад я лишился части постоянного дохода и стал это довольно остро ощущать. Тут-то и вспомнились красные трусы, и я уже почти решил поддаться минутной слабости и испытать их волшебную силу, но возникла другая проблема — у меня в комнате нет люстры. В общем, как вы уже догадались, я снова отложил красные трусы в долгий ящик — можно сказать, в буквальном смысле этого слова. И вот пару дней назад коллега рассказала, что все маркетплейсы буквально заполнены тем самым аксессуаром. Полез убедиться — и точно! Примерно за 600 рублей можно приобрести целый магический набор — собственно красные женские трусы (несправедливо, кстати, про мужчин никто не подумал), пузырек масла пачули и подробную инструкцию к применению. Не веря своим глазам, я ознакомился. И понял, что не зря когда-то не довел дело до конца — я же не знал ритуала, поэтому и чуда бы не произошло бы. Зато теперь все ясно и понятно.

«Загадайте необходимую вам сумму, постирайте трусы в теплой воде с добавлением масла пачули, включите любимую музыку, танцуйте», — пишут неведомые авторы инструкции. Дальше фантазия продавцов счастья разыгрывается по полной — трусы предлагается сначала надеть на голову, а потом закинуть на люстру предпочтительно левой ногой, при этом приговаривая: «Трусы на люстру — деньги в дом». Когда изделие китайской трикотажной промышленности как следует закрепится на люстре, скажите шепотом: «Поперло!» — и ждите. Желаемая сумма должна появиться у вас примерно через три месяца.

Смешно, скажете вы? Еще как. Возмутительно? Ну конечно! Дурят народ почем зря, отвлекают от реальных дел. Ложную надежду дают опять же и учат рассчитывать на какие-то подозрительные чудеса вместо собственных сил. Посмотрел комментарии под товаром — был уверен, что бдительные граждане разоблачат шутников с трусами. Опять ошибся — там у всех все работает! Какие-то деньги людям поступают (откуда, хотелось бы знать? Наверно с лотереи?), а некоторые даже замуж выходят. Есть и такие, которые все еще не разбогатели, но не сдаются — ждут и верят. И не только женщины, кстати, мужчины там тоже встречаются, хотя их, конечно, меньшинство. То ли они стесняются, то ли более трезво смотрят на жизнь.

Лааадно. Все-таки комментарии на маркетплейсах, сами знаете, дело темное. Мало ли там кто-что пишет — сложно верить.

Стал говорить с подругами — самостоятельными, серьезными, обеспеченными женщинами, — оказалось, среди них полно любителей двойных стандартов! Бред бредом, говорят, а трусы тихонечко на какую-то лампочку нет-нет, да и пристроят. Ногами не закидывают, конечно, потому что если у тебя такой батман, простите, ты и без красных трусов вполне себе обойдешься — мужчины скорее всего уже в очереди стоят. Да, руками, да, без пачули, и даже «поперло» не говорят, но ведь работает, блин!

В общем, теперь я сомневаюсь. С одной стороны, я по-прежнему верю, что в жизни человек должен прежде всего рассчитывать на себя и прикладывать максимум усилий для достижения оптимального результата в любом деле. С другой — кому и когда мешали красные трусы на люстре? В конце концов, в любой момент можно прекратить эксперимент и использовать этот предмет по прямому назначению. В общем, теперь дело за малым — приобрести люстру и начать после работы тренироваться закидывать на нее хоть что-то, да еще левой ногой для достижения оптимального результата. Дело это непростое, попробуйте сами, если не верите. Когда научусь и куплю красные трусы, сообщу. Наверняка вам тоже нужно, чтобы наконец-то «поперло».

Russia has reportedly cut some regions of the country off from the rest of the world's internet for a day, effectively siloing them, according to reports from European and Russian news outlets reshared by the US nonprofit Institute for the Study of War (ISW) and Western news outlets.

Russia has reportedly cut some regions of the country off from the rest of the world's internet for a day, effectively siloing them, according to reports from European and Russian news outlets reshared by the US nonprofit Institute for the Study of War (ISW) and Western news outlets.Russia's communications authority, Roskomnadzor, blocked residents in Dagestan, Chechnya, and Ingushetia, which have majority-Muslim populations, ISW says. The three regions are in southwest Russia near its borders with Georgia and Azerbaijan. People in those areas couldn't access Google, YouTube, Telegram, WhatsApp, or other foreign websites or apps—even if they used VPNs, according to a local Russian news site.

Russian digital rights NGO Roskomsvoboda told that most VPNs didn't work during the shutdown, but some apparently did. It's unclear which ones or how many actually worked, though. Russia has been increasingly blocking VPNs more broadly, and Apple has helped the country's censorship efforts by taking down VPN apps on its Russian App Store. At least 197 VPNs are currently blocked in Russia, according to Russian news agency Interfax.

These latest partial internet blocks are because Russia is testing its own sovereign internet it can fully control. Russia already tested blocking or throttling sites like YouTube this year by slowing down speeds so much that sites are virtually unusable. Russia has reportedly poured $648 million into its national internet and tech that can power restrictions and has been seemingly working on this since at least 2019.

In the future, Russia could also block Amazon Web Services (AWS), HostGator, and other foreign web hosts. The country may also force Russian residents and companies to stop using such services and migrate over to Russian-owned ones so the government can enforce its own rules.

Separately, in September, the Wix and Notion platforms told Russian users to stop using their sites due to US sanctions. And back in 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine, Western domain registrar GoDaddy condemned the war as "horrible," stopped supporting Russian domains, ditched Russia's currency, and announced it was donating $500,000 to support Ukraine. All of these blocks and disconnections contribute to the splinternet(An Internet that is increasingly fragmented due to nations filtering content or blocking it entirely for political purposes. Splinternet also occurs when apps use their own standards for accessing data, which differs from the universality of the Web (browsers, websites, HTTP protocol, etc.) we're hurtling toward today.

China is another country known for its internet censorship. Colloquially dubbed the "Great Firewall" in reference to the Great Wall of China, internet access in China has been censored in this way for over a decade, but Chinese internet censorship efforts first began back in 1998 with China's "Golden Shield" project. In recent years, China has censored even single letters as well as keywords it deems unwanted and unacceptable for the internet. Video streaming sites and meeting platforms like Zoom have also been censored, along with a slew of other foreign apps. It's unclear, however, to what extent Russian internet censorship might mirror these policies.

VPNs, which stand for virtual private networks, can allow users to get around certain geographic restrictions by virtually locating the user in another country. But VPNs aren't a one-size-fits-all solution and can be censored. Internet providers are able to tell if a user has a VPN enabled and can block access to sites in some circumstances. In the US, streaming platforms like Netflix and some shopping sites have blocked VPN users globally by determining whether an IP address is tied to a VPN provider or appears to be in a different location from the user's internet provider.

VPN use has historically spiked when internet censorship appears. US Pornhub users in some states have been looking for VPNs to get around state-level blocks, and Hong Kong residents flocked to VPNs when China announced a new security law, to name two examples from the past few years. But Iran, Cuba, Myanmar, Vietnam, and Saudi Arabia are also considered to offer little internet freedom. While VPNs can help some for now, they're not a perfect solution and may not work forever.

Economic Resistance By Putin

Nov. 30th, 2024 08:23 am Russia just put Bitcoin at the center of its economic chessboard. Earlier today, President Vladimir Putin signed a law that not only recognizes Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies as legal property but also brings a lot of new regulations to the industry.

Russia just put Bitcoin at the center of its economic chessboard. Earlier today, President Vladimir Putin signed a law that not only recognizes Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies as legal property but also brings a lot of new regulations to the industry.The new law rewrites Russia’s Tax Code, turning crypto into a taxable asset. It exempts mining and sales from value-added tax (VAT), but miners must report their activities to local authorities or risk a fine of 40,000 rubles (about $380).

Trading profits are also on the radar, with a tiered tax system: 13% for earnings under 2.4 million rubles ($22,300) and 15% for anything higher.

Starting next year, all crypto companies will face a standard tax rate of 25%. Most parts of this law are effective immediately, except for a few delayed clauses.

Russia anticipates collecting up to 200 billion rubles (around $2 billion) annually from its booming crypto mining sector. And given the country’s global rank as a mining powerhouse, the numbers don’t seem at all far-fetched.

Russia has consistently ranked among the top players in crypto mining, with its abundance of cheap energy fueling massive operations. Now on November 1, a government-backed database for large-scale miners was launched under a separate law Putin signed in August.

The stakes are bigger than just domestic control. Russia’s Central Bank has also greenlit a pilot program for cross-border crypto transactions. These transactions are seen as a lifeline for Moscow, allowing the country to sidestep sanctions and purchase restricted goods on international markets.

Crypto’s decentralized nature makes it harder for Western regulators to track, giving Russia a potential edge in accessing critical resources — military or otherwise.

Of course, this doesn’t sit well with the United States. Washington has warned banks in countries like China, Turkey, and the UAE against aiding Moscow’s efforts to bypass sanctions. But let’s be honest, Moscow isn’t losing sleep over U.S. threats these days.

While Putin is busy legitimizing Bitcoin, the ruble is hitting rock bottom. This week, it sank to 114 against the U.S. dollar, its weakest since March 2022. Russia’s central bank had to step in, halting foreign currency purchases on the domestic market to stabilize the ruble.

By Thursday, it had clawed back some ground, trading at 110 to the dollar, but the damage was done. Putin, as usual, downplayed the crisis. “There are absolutely no grounds for panic,” he said, attributing the ruble’s slide to seasonal factors and budgetary payments.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov chimed in, insisting the decline wouldn’t affect ordinary Russians because they earn salaries in rubles. Sure. But analysts aren’t buying it.

Timothy Ash, an emerging markets strategist, described the ruble as being in “free fall,” calling it a proper currency crisis in the making. A weaker ruble means higher inflation, rising interest rates, and slower economic growth.

Inflation was already at 8.5% in October, with staples like butter and potatoes costing significantly more than last year. But don’t get it twisted, the currency collapse is tied to more than just seasonal changes.

New U.S. sanctions targeting Gazprombank have added pressure, while Russia’s war-driven economy is stretching resources thin. Defense spending has skyrocketed, with funds pouring into domestic weapons production.

Despite this, Putin denies the country is sacrificing consumer welfare for military priorities, famously rejecting the notion of “butter for guns.” Meanwhile, the International Monetary Fund recently revised its GDP forecast for Russia, projecting 3.6% growth in 2024.

That’s not bad considering the circumstances, but the IMF also warned of a slowdown in 2025, with growth expected to drop to 1.3%. Private consumption and investment are slowing, labor markets are tightening, and wage growth is losing steam.

As the ruble crumbles and sanctions bite, looks like Bitcoin is stepping up both as a tool and a symbol of economic resistance.

Как Выжить? Валить!

Nov. 26th, 2024 09:56 am Сергея мобилизовали в октябре 2022 года. Он рассказывает, что его остановили полицейские в Москве, проверили паспорт и заявили, что в Нижнем Новгороде, где он когда-то проживал, его ждет повестка в военкомат. Когда Сергей отказался от предложения туда поехать, полицейские сунули ему в карман какой-то сверток, а затем позвали понятых. В свертке оказался наркотик мефедрон. После этого полицейские пригрозили Сергею, что дадут ход уголовному делу, если он не отправится в военкомат.

Сергея мобилизовали в октябре 2022 года. Он рассказывает, что его остановили полицейские в Москве, проверили паспорт и заявили, что в Нижнем Новгороде, где он когда-то проживал, его ждет повестка в военкомат. Когда Сергей отказался от предложения туда поехать, полицейские сунули ему в карман какой-то сверток, а затем позвали понятых. В свертке оказался наркотик мефедрон. После этого полицейские пригрозили Сергею, что дадут ход уголовному делу, если он не отправится в военкомат.В военкомате Нижнего Новгорода Сергей, по его словам, сразу предупредил, что не собирается брать в руки оружие и стрелять в кого-либо на фронте. «Я говорил, что у меня ну прям табу на убийства — это для меня стремная история, с этим еще жить потом, мне это не надо. Даже не конкретно украинцев, а вообще», — рассказывает он. Сотрудники военкомата спросили, какая профессия у него была «на гражданке», он ответил, что чинил бытовую технику, а в военной специальности записан как электрик — в этом качестве его и отправили на базу для мобилизованных под Костромой.

Там Сергей выяснил, что будет служить не электриком, а обычным пехотинцем. Но он смог договориться с командованием, чтобы его взяли анестезиологом в медицинскую роту. Савченко вспоминает, что перед этим ему задавали общие вопросы, ответы на которые он знал, потому что был «чуть-чуть подкован». «Какие, грубо говоря, могут быть причины смерти на войне? А это всегда шок — либо геморрагический, либо болевой, либо анафилактический», — говорит он.

До мая 2023 года Сергей служил в Сватовском районе Луганской области. Он вспоминает, что «поток раненых был огромный». Затем ему дали отпуск. Также Сергей получил две медали, но это стало одной из причин того, что его, как и всех остальных из его полка, «кто не идиот», отправили на офицерские курсы. Отказаться от них Савченко не смог — в противном случае ему пригрозили отправкой в штурмовой отряд.

Курсы проходили три месяца в Наро-Фоминском районе Московской области. Когда Сергей вернулся на фронт, его назначили командиром взвода, а затем отдали приказ штурмовать укрепления ВСУ. Он отказался. «Я был готов идти на передок, но только за ранеными, не более того. Я с самого начала говорил, что не буду ни сам стрелять, ни отдавать приказы стрелять в кого-либо», — вспоминает Сергей. Через несколько дней его задержали и сначала увезли в расположение его бывшего подразделения, а затем в село Зайцево в той же Луганской области, где, как сообщал телеграм-канал Astra, находится нелегальная тюрьма для российских военных, отказавшихся выполнять приказы.

По словам Сергея, в тюрьме, которая представляла собой подвал бывшей украинской таможни, он провел с другими заключенными 72 дня. Он рассказывает, что его каждый день выводили из подвала и пытали. «Происходило это разнообразно: нет-нет, да током били, обливали холодной водой часа по полтора-два, прям из шланга, просто били… Это не ради каких-то там показаний, это просто ежедневные спецэффекты, чтобы ты очень сильно хотел оттуда уйти, куда угодно», — вспоминает Сергей.

Его забрали из Зайцево 26 декабря и вместе с другими отказниками отвезли в оккупированную часть Харьковской области, а затем через два дня в расположение 25-й гвардейской мотострелковой бригады ВС РФ. Сергей и тогда сообщил замполиту, что отказывается стрелять в людей. Из-за этого его привязали на ночь к дереву, но утром отвели к начальнику медицинской службы одного из штурмовых отрядов. Тот предложил Сергею заняться эвакуацией раненых за взятку в 100 тысяч рублей.

Сергею разрешили позвонить жене, она перевела деньги (на обычную карту Сбера, привязанную к телефону начальника), и Сергей получил должность эвакуатора. «Все суетят там деньги постоянно. Грубо говоря, хочешь быть водителем — покупай „буханку“ и будешь водителем. Хочешь на задачу пойти не сегодня, а попозже, чуть-чуть еще пожить — давай бабки, поживи», — рассказывает Сергей.

В эвакуации Сергей проработал больше двух месяцев. В марте он получил приказ отправиться на передовую в качестве штурмовика и решил выбираться с фронта «любой ценой». Он попросил водителя эвакуационного автомобиля отвезти его в штаб бригады, нашел там прикомандированного к части контрразведчика из ФСБ, предложил себя допросить и рассказал ему про взятки. После этого Сергея на три ночи заперли в клетке на улице, а затем перевели в расположение гаубичного дивизиона бригады.

Все это время жена Сергея, по его словам, постоянно писала обращения в Минобороны, Генпрокуратуру, Следственный комитет РФ. В мае, после очередного такого обращения, Сергея угрозами заставили написать бумагу, что он не имеет претензий «к должностным лицам Минобороны» и просит прекратить «проверочные мероприятия» в отношении него. Сергей вспоминает, что к тому времени он «болтался как свободный офицер» в расположении дивизиона и «приглядывал за порядком, чтобы никто не бухал».

В июне 2024 года, услышав разговоры по телефону одного из бойцов по соседству в блиндаже, Сергей попросил у него контакты заместителя главы военно-следственного отдела в Луганске и связался с ним. Тот пообещал, что вывезет его из расположения дивизиона за миллион рублей. Эти деньги жена Сергея заняла по друзьям, и в сентябре за Сергеем приехали из Следственного комитета и забрали в Луганск. Месяц Сергей работал в СК — по собственным словам, бесплатно и по 12 часов в день без выходных. А затем в следственный отдел вернулся из отпуска начальник, и Сергей понял, что тот ничего не знает о взятке.

По словам Сергея, с начальником договориться уже не удалось, и ему сказали, что скоро за ним приедут обратно из бригады. Тогда он решил бежать. Сергей придумал себе легенду, что он — руководитель строительной фирмы из Ростова-на-Дону, который ездил в Луганск смотреть объекты для реконструкции. Он добрался до Ростова, сел на поезд, сошел на случайной станции, где «посветил лицом перед камерами», а оттуда на попутной машине отправился дальше. Осенью 2024 года он покинул Россию с помощью проекта «Идите лесом», который оказывает поддержку тем, кто бежит с фронта или от мобилизации.

Как рассказывает Сергей, во время работы в луганском СК он сделал запрос в Единый расчетный центр Минобороны РФ и узнал, что числится пропавшим без вести с 29 декабря 2023 года — то есть дня, когда его после тюрьмы в Зайцево привезли в расположение 25-й бригады. По словам Сергея, бойцов этой бригады признавали пропавшими без вести массово — и когда он узнал о награждении командира бригады Алексея Ксенофонтова, у него «сложился пазл».

«Он получал Героя России за штурмы без потерь, а штурмы без потерь получаются потому, что пацанов туда пригоняют, сразу объявляют без вести пропавшими и отправляют на мясо. Эта мразь потом получит звание генерал-майора, уйдет на пенсию и пойдет во власть, станет офигенным депутатом. А из-за него тем временем пять тысяч пацанов там лежало, через кого-то уже росли кусты, трупы не вытаскивали, потому что за трупы надо платить, и трупы надо признавать трупами», — говорит Сергей.

Bomb Threats To Polling Places

Nov. 5th, 2024 12:16 pm Bomb threats that have slowed or delayed polling processes around the nation appear to be tied to a slew of Russian email addresses, the FBI said in a Tuesday afternoon statement.

Bomb threats that have slowed or delayed polling processes around the nation appear to be tied to a slew of Russian email addresses, the FBI said in a Tuesday afternoon statement.“The FBI is aware of bomb threats to polling locations in several states, many of which appear to originate from Russian email domains. None of the threats have been determined to be credible thus far,” the statement reads.

Russia propagated a fake bomb threat targeting a polling place in Georgia, whose Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger said Tuesday such a threat was not credible(MOre details: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/elections/2024/11/05/georgia-bomb-threat-russians/76068592007).

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency has not observed any sustained, coordinated influence operation that’s been built on the bomb threats, though agency senior advisor Cait Conley said “we should not be surprised if we do, because, as we’ve been saying for months, our foreign adversaries will seek out opportunities and capitalize on those opportunities” to undermine confidence in the administration of the election.

Moscow has built a stacked record of election disinformation attempts over the past several months, aiming to tip the scales of the election in favor of former President Donald Trump, previous intelligence assessments have stated.

“We are in communication with impacted entities and will continue to provide support as possible,” said Conley in a Tuesday afternoon briefing with reporters. “While incidents may occur and things like this may cause temporary disruptions to the process, there are measures in place that election officials have implemented to ensure the security and resilience of the overall election administration process.”

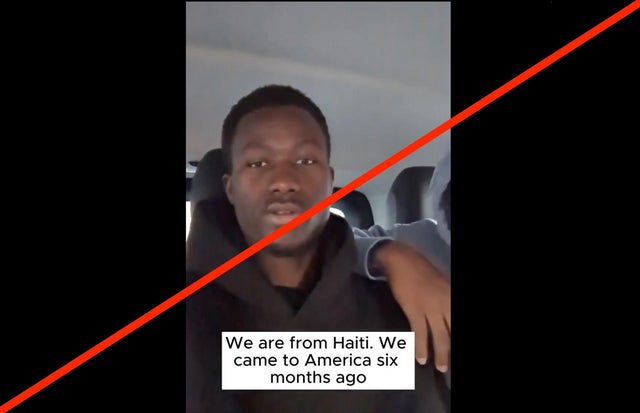

Kremlin spin doctors are responsible for creating a video purporting to show a person from Haiti claiming to have fraudulently voted several times in counties around Georgia, the U.S. intelligence community said Friday.

Kremlin spin doctors are responsible for creating a video purporting to show a person from Haiti claiming to have fraudulently voted several times in counties around Georgia, the U.S. intelligence community said Friday.The video, which has been shared by some well-known Republicans, depicts a man alleging he immigrated from Haiti six months ago and swiftly gained U.S. citizenship. He claims to possess multiple state IDs, allowing him to vote for Kamala Harris across multiple counties in Georgia. The man also encourages all Haitians to move to America with their families.

“This judgment is based on information available to the IC and prior activities of other Russian influence actors, including videos and other disinformation activities. The Georgia Secretary of State has already refuted the video’s claims as false,” said the statement from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and the FBI.

Yesterday, Georgia’s Republican Secretary of State, Brad Raffensperger, asked X to remove the video involving the purported Haitian man. “This is false and a clear example of targeted disinformation in this election,” Raffensperger wrote, suggesting it was likely “created by Russian troll farms.”

Another video accusing a person tied to Vice President Kamala Harris’s campaign of taking a bribe from a U.S. entertainer was also manufactured by Russia, according to the intelligence community’s statement.

An official from the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, speaking on the condition of anonymity under agency-set press guidelines, said the U.S. is “very concerned about how our foreign adversaries will specifically target after Election Day” during the period of time in which state and local officials undertake procedures to certify the election’s results.

That time window “is an opportunity where our adversaries are likely to try to capitalize and to undermine the American people’s confidence in the outcome of the election, regardless of who wins,” the CISA official said.

Recent foreign influence attempts leading up to Nov. 5 are keeping officials hyper alert. The efforts have accelerated in recent weeks and months, conducted by Russia, Iran and China, the latter two of which have successfully compromised tangible confidential data or communications of the two major presidential campaigns that are deadlocked in national polls.

Russian election disinformation campaigns “pose a real risk,” Neal Higgins, a former deputy White House national cyber director, said in an interview.

“The Russians have made clear that they are determined to use disinformation to undermine American democracy. Eight years ago that was through leaked emails and false stories,” said Higgins, a partner at law firm Eversheds Sutherland. “Now it’s through cheap-fake and deep fake videos, including videos falsely alleging election irregularities.”

Russia's Secret Weapon

Oct. 12th, 2024 02:15 pm When two white vapour trails cross the sky near the front line in eastern Ukraine, it tends to mean one thing. Russian jets are about to attack.

When two white vapour trails cross the sky near the front line in eastern Ukraine, it tends to mean one thing. Russian jets are about to attack.But what happened near the city of Kostyantynivka was unprecedented. The lower trail split in two and a new object quickly accelerated towards the other vapour trail until they crossed and a bright orange flash lit up the sky.

Was it, as many believed, a Russian war plane shooting down another in so-called friendly fire 20km (12 miles) from the front line, or a Ukrainian jet shooting down a Russian plane?

Intrigued, Ukrainians soon found out from the fallen debris that they had just witnessed the destruction of Russian’s newest weapon - the S-70 stealth combat drone.

This is no ordinary drone. Named Okhotnik (Hunter), this heavy, unmanned vehicle is as big as a fighter jet but without a cockpit. It is very hard to detect and its developers claim it has “almost no analogy” in the world.

That all may be true, but it clearly went astray, and it appears the second trail seen on the video came from a Russian Su-57 jet, apparently chasing it down.

The Russian plane may have been trying to re-establish the contact with the errant drone, but as they were both flying into a Ukrainian air defence zone, it is assumed a decision was made to destroy the Okhotnik to prevent it ending up in enemy hands.

Neither Moscow nor Kyiv have commented officially on what happened in the skies near Kostyantynivka. But analysts believe the Russians most likely lost control over their drone, possibly due to jamming by Ukraine’s electronic warfare systems.

This war has seen many drones but nothing like Russia’s S-70. It weighs more than 20 tonnes and reputedly has a range of 6,000km (3,700 miles).

Shaped like an arrow, it looks very similar to American X-47B, another stealth combat drone created a decade ago.

The Okhotnik is supposed to be able to carry bombs and rockets to strike both ground and aerial targets as well as conduct reconnaissance.

And, significantly, it is designed to work in conjunction with Russia’s fifth-generation Su-57 fighter jets.

It has been under development since 2012 and the first flight took place in 2019.

But until last weekend there was no evidence that it had been used in Russia’s two-and-a-half-year war in Ukraine.

Earlier this year it was reportedly spotted at the Akhtubinsk airfield in southern Russia, one of the launch sites to attack Ukraine.

So it is possible the abortive flight over Kostyantynivka was one of Moscow’s first attempts to test its new weapon in combat conditions.

Wreckage of one of Russia’s notorious long-range D-30 glide bombs was reportedly found amidst the aircraft’s crash site.

These deadly weapons use satellite navigation to become even more dangerous.

So what was the Okhotnik doing flying with an Su-57 jet? According to Kyiv-based aviation expert Anatoliy Khrapchynskyi, the warplane may have transmitted a signal from a ground base to the drone to increase the extent of their operation.

The stealth drone’s failure is no doubt a big blow for Russia’s military. It was due to go into production this year but clearly the unmanned aircraft is not ready.

Four protype S-70s are thought to have been built and it is possible the one blown out of the sky over Ukraine was the most advanced of the four.

Even though it was destroyed, Ukrainian forces may still be able to glean valuable information about the Okhotnik.

“We may learn whether it has its own radars to find targets or whether the ammunition is pre-programmed with co-ordinates where to strike,” explains Anatoliy Khrapchysnkyi.

Just by studying images from the crash site, he believes it is clear the drone’s stealth capabilities are rather limited.

As the engine nozzle’s shape is round, he says it can be picked up by radar. The same goes for the many rivets on the aircraft which are most likely made of aluminium.

No doubt the wreckage will be pored over by Ukrainian engineers and their findings passed on to Kyiv’s Western partners.

And yet, this incident shows the Russians are not standing still, reliant on their massive human resources and conventional weapons.

They are working on new and smarter ways to fight the war. And what failed today may succeed next time.

The Kremlin is Hunting Down

Sep. 29th, 2024 08:59 am In December 2022, Elena Kostyuchenko discovered she had been poisoned in Germany, in a probable assassination attempt by the Russian state(More details: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/sep/12/you-may-have-been-poisoned-how-an-independent-russian-journalist-became-a-target).

In December 2022, Elena Kostyuchenko discovered she had been poisoned in Germany, in a probable assassination attempt by the Russian state(More details: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/sep/12/you-may-have-been-poisoned-how-an-independent-russian-journalist-became-a-target).Such stories have become routine.

Last year, an investigative journalist, Alesya Marokhovskaya, was harassed in the Czech Republic; in February, the bullet-riddled body of a Russian defector, Maxim Kuzminov, was found in Spain. In both cases, the Kremlin was assumed to be involved. Russian opposition figures know well that even in exile they remain targets of Russia’s intelligence services( Details: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cl4y0j47xe4o.amp and https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/20/world/europe/russian-pilot-maksim-kuzminov-spain.html).

But it’s not just them who are in danger. There are also the hundreds of thousands of Russians who left home because they did not want to have anything to do with Vladimir Putin’s war — or were forced out, accused of not embracing it enough. These low-profile dissenters are subjected to surveillance and kidnappings, too. Yet their repression happens in silence — away from the spotlight and often with the tacit consent, or inadequate prevention, of the countries to which they have fled.

It’s a terrifying thing: The Kremlin is hunting down ordinary people across the world, and nobody seems to care.

If you will gathering information about Russia’s targeting of exiles since the start of the war in Ukraine and your sources will range from people who themselves survived abductions and surveillance to the leaders of Russian diasporas around the world — and the few human rights activists helping them then many spoke to you on the condition of anonymity in order to discuss Russian repression without fear of reprisal. The Kremlin, of course, denies any involvement — mostly saying that it cannot comment on what is happening to people in other countries. But the evidence is piling up.

There’s a vocal coach arrested in Kazakhstan at Moscow’s request who went mad in a local jail. A caregiver for the elderly detained in Montenegro on Russian orders, carried out by Interpol. A schoolteacher detained by Armenian border guards after telling her students about Russia’s crimes in Bucha. A toy shop owner, an industrial climber, a punk rocker: These are some of the people caught in the Kremlin dragnet, all over the world(Details: https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakhstan-russia-peace-activist-extradition/32626069.html and https://portmedia.info/news/v-chernogorii-zaderzhana-grazhdanka-rossii-s-italyanskim-ubezhishhem and https://meduza.io/news/2024/07/13/v-aeroportu-erevana-zaderzhali-uchitelnitsu-iz-podmoskovya-natalyu-taranushenko-v-rossii-na-nee-zaveli-delo-o-feykah-pro-armiyu-posle-razgovora-s-detmi-o-voyne and https://www.svoboda.org/a/prityazhenie-rodiny-kak-fsb-vykrala-iz-gruzii-politemigranta/32718799.html and https://novayagazeta.eu/articles/2024/08/13/rossiianin-kotoryi-byl-vyvezen-iz-uzbekistana-i-arestovan-v-moske-priznalsia-v-gosizmene-news and https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-antiwar-activist-disappears-yakutsk-/32182078.html).

And it is a truly global operation. In Britain, exiles are being followed and London opposition events are crawling with agents “who stick out like a sore thumb,” Ksenia Maximova, an anti-Kremlin activist there, told me. Russian intelligence officers have been sent to monitor the diasporas in Germany, Poland and Lithuania, according to Evgeny Smirnov, a lawyer who specializes in treason and espionage cases. Other emigrants have been stalked and threatened in Rome, Paris, Prague and Istanbul. The list goes on.

Some of the methods are especially insidious. Lev Gyammer, an exiled activist in Poland, has been receiving texts for two years, supposedly from his mother. “Levushka, son, I miss you so, when will you visit me?”(More details: https://theins.ru/news/262275). Another reads, “Son, I’m waiting for you. Come back soon.” He ignores them: His mother, Olga, died five years ago. Another Russian expatriate — whose elderly parents are still alive and very sick — chose to believe it when his parents’ nurse of many years told him, over the phone, of a fire in their apartment. He rushed home from Finland and was immediately taken to prison and tortured, according to Mr. Smirnov. Of course, there never was a fire.

Those who cannot be tricked back to Russia are subjected to surveillance. An employee of an organization that supports L.G.B.T.Q. people was walking her dog around the neighborhood in Tbilisi, Georgia, when she noticed that she was being followed by a drone. It was an evening in early May — two years since she’d fled Russia with the rest of her colleagues. She hurried back to hide at her apartment but could still hear the buzzing. She followed the noise to the balcony and came face to face with the device, hanging there within arm’s reach.

Host countries are often complicit. In some places, local police officers even conduct surveillance on behalf of their Russian colleagues. In Kazakhstan, local special services are helping Russia catch draft dodgers. In Kyrgyzstan, the police are using facial recognition technology to search for those wanted by the Kremlin, forcing people to leave cities for the mountains, according to a host of advocacy groups. When not actively assisting Russian surveillance, the local authorities are sometimes slow to stop it(https://www.rferl.org/a/kamil-kasimov-russia-army-kazakhstan-ukraine-war-sentence/33105887.html and https://www.currenttime.tv/a/posolstvo-rasporyadilos-deportirovat-vseh-uehavshie-v-kyrgyzstan-rossiyane-govoryat-o-slezhke-i-chto-konsulstvo-rf-trebuet-ih-vysylki/32311745.html).

This was the case with Sergei Podsytnik, a journalist investigating military links between Russia and Iran. In March of this year, still elated by the news that a drone factory he’d uncovered was getting sanctioned, he was returning to his room in Duisburg, Germany. Before going into exile, Mr. Podsytnik was part of Alexei Navalny’s opposition network and picked up the habit of making sure he wasn’t being followed. Outside his door, he casually glanced over his shoulder — and saw, peeking out from around the corner, a stranger following his every move(More details: https://ofac.treasury.gov/recent-actions/20240223).

Mr. Podsytnik’s colleague also noticed that he was being watched by the same man, but it took them two appeals to secure an investigation from the local authorities. The police in Duisburg simply could not comprehend that it was possible for Russia-sponsored surveillance to be happening in their town, it seemed. The case was soon closed without finding the offender, which might’ve been a mistake. Duisburg is one of the places, according to the Dossier Center, a London-based research organization, from which agents of the Russian military intelligence unit have carried out sabotage abroad(More details: https://dossier.center/diversion/).

Mr. Podsytnik is safe now, but not everyone has been so lucky. Exiles who’ve experienced similar surveillance sometimes end up disappearing without a trace — be it from the doorstep of an embassy in Armenia or a rural church in Georgia — only to turn up in Russian detention centers. It is impossible to gauge how often this is happening. Yet we can assume, some sources say, that there are many more cases like that of Lev Skoryakin, who was taken from his hostel in Kyrgyzstan last October, shoved into a car and deported back to Russia. We just don’t know about them(More details: https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2023/11/03/russian-activist-found-in-moscow-jail-after-disappearing-in-kyrgyzstan-a82993).

Many Russians abroad are vulnerable and lack protection. In the summer of 2023, civil society groups petitioned(https://www.4freerussia.org/press-center/we-are-agents-of-change-the-speech-by-frfs-president-natalia-arno-at-the-european-parliament) the European Parliament to help with the legalization of people who refused to fight in Mr. Putin’s army; there was no meaningful response. Political asylum is routinely denied not only to draft dodgers but also to activists — sometimes “with monstrous arguments that ‘the situation in Russia is normal and you can count on a fair trial,’” Margarita Kuchusheva, an immigration lawyer in Cyprus, told...

Antiwar exiles are supported by a handful of human rights organizations, perennially on the brink of closing because of lack of funds. Russia, by contrast, lavishes a great deal of resources on the exiles — as it accuses them of treason and terrorism and, driven by paranoia, pursues them all over the world. They are at immediate risk. But the greater danger is that the world forgets altogether about these people — and why they left their country in the first place.

The War in Ukraine is Going Badly

Sep. 26th, 2024 05:03 pm If Ukraine and its Western backers are to win, they must first have the courage to admit that they are losing. In the past two years Russia and Ukraine have fought a costly war of attrition. That is unsustainable. When Volodymyr Zelensky travelled to America to see President Joe Biden this week, he brought a “plan for victory”, expected to contain a fresh call for arms and money. In fact, Ukraine needs something far more ambitious: an urgent change of course.

If Ukraine and its Western backers are to win, they must first have the courage to admit that they are losing. In the past two years Russia and Ukraine have fought a costly war of attrition. That is unsustainable. When Volodymyr Zelensky travelled to America to see President Joe Biden this week, he brought a “plan for victory”, expected to contain a fresh call for arms and money. In fact, Ukraine needs something far more ambitious: an urgent change of course.A measure of Ukraine’s declining fortunes is Russia’s advance in the east, particularly around the city of Pokrovsk. So far, it is slow and costly. Recent estimates of Russian losses run at about 1,200 killed and wounded a day, on top of the total of 500,000. But Ukraine, with a fifth as many people as Russia, is hurting too. Its lines could crumble before Russia’s war effort is exhausted.

Ukraine is also struggling off the battlefield. Russia has destroyed so much of the power grid that Ukrainians will face the freezing winter with daily blackouts of up to 16 hours. People are tired of war. The army is struggling to mobilise and train enough troops to hold the line, let alone retake territory. There is a growing gap between the total victory many Ukrainians say they want, and their willingness or ability to fight for it.

Abroad, fatigue is setting in. The hard right in Germany and France argue that supporting Ukraine is a waste of money. Donald Trump could well become president of the United States. He is capable of anything, but his words suggest that he wants to sell out Ukraine to Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin.

If Mr Zelensky continues to defy reality by insisting that Ukraine’s army can take back all the land Russia has stolen since 2014, he will drive away Ukraine’s backers and further divide Ukrainian society. Whether or not Mr Trump wins in November, the only hope of keeping American and European support and uniting Ukrainians is for a new approach that starts with leaders stating honestly what victory means.

Mr Putin attacked Ukraine not for its territory, but to stop it becoming a prosperous, Western-leaning democracy. Ukraine’s partners need to get Mr Zelensky to persuade his people that this remains the most important prize in this war. However much Mr Zelensky wants to drive Russia from all Ukraine, including Crimea, he does not have the men or arms to do it. Neither he nor the West should recognise Russia’s bogus claim to the occupied territories; rather, they should retain reunification as an aspiration.

In return for Mr Zelensky embracing this grim truth, Western leaders need to make his overriding war aim credible by ensuring that Ukraine has the military capacity and security guarantees it needs. If Ukraine can convincingly deny Russia any prospect of advancing further on the battlefield, it will be able to demonstrate the futility of further big offensives. Whether or not a formal peace deal is signed, that is the only way to wind down the fighting and ensure the security on which Ukraine’s prosperity and democracy will ultimately rest.

This will require greater supplies of the weaponry Mr Zelensky is asking for. Ukraine needs long-range missiles that can hit military targets deep in Russia and air defences to protect its infrastructure. Crucially, it also needs to make its own weapons. Today, the country’s arms industry has orders worth $7bn, only about a third of its potential capacity. Weapons firms from America and some European countries have been stepping in; others should, too. The supply of home-made weapons is more dependable and cheaper than Western-made ones. It can also be more innovative. Ukraine has around 250 drone companies, some of them world leaders—including makers of the long-range machines that may have been behind a recent hit on a huge arms dump in Russia’s Tver province.

The second way to make Ukraine’s defence credible is for Mr Biden to say Ukraine must be invited to join nato now, even if it is divided and, possibly, without a formal armistice. Mr Biden is known to be cautious about this. Such a declaration from him, endorsed by leaders in Britain, France and Germany, would go far beyond today’s open-ended words about an “irrevocable path” to membership.

This would be controversial, because NATO’s members are expected to support each other if one of them is attacked. In opening a debate about this Article 5 guarantee, Mr Biden could make clear that it would not cover Ukrainian territory Russia occupies today, as with East Germany when West Germany joined NATO in 1955; and that Ukraine would not necessarily garrison foreign NATO troops in peacetime, as with Norway in 1949.

NATO membership entails risks. If Russia struck Ukraine again, America could face a terrible dilemma: to back Ukraine and risk war with a nuclear foe; or refuse and weaken its alliances around the world. However, abandoning Ukraine would also weaken all of America’s alliances—one reason China, Iran and North Korea are backing Russia. Mr Putin is clear that he sees the real enemy as the West. It is deluded to think that leaving Ukraine to be defeated will bring peace.

Indeed, a dysfunctional Ukraine could itself become a dangerous neighbour. Already, corruption and nationalism are on the rise. If Ukrainians feel betrayed, Mr Putin may radicalise battle-hardened militias against the West and nato. He managed something similar in Donbas where, after 2014, he turned some Russian-speaking Ukrainians into partisans ready to go to war against their compatriots.

For too long, the West has hidden behind the pretence that if Ukraine set the goals, it would decide what arms to supply. Yet Mr Zelensky cannot define victory without knowing the level of Western support. By contrast, the plan outlined above is self-reinforcing. A firmer promise of NATO membership would help Mr Zelensky redefine victory; a credible war aim would deter Russia; NATO would benefit from Ukraine’s revamped arms industry. Forging a new victory plan asks a lot of Mr Zelensky and Western leaders. But if they demur, they will usher in Ukraine’s defeat. And that would be much worse.