У Вашингтоні у Ukraine House до 19 січня діє виставка «Українські нонконформістські художники у Парижі 1980-х: у пошуках свободи самовираження». Експозиція має на меті познайомити американську публіку з маловідомою, але надзвичайно важливою сторінкою української історії мистецтва. Проєкт зосереджений на творчості митців, які сформувалися в умовах радянської системи, але свідомо обрали шлях художньої свободи всупереч ідеологічним обмеженням.

В експозиції представлені роботи чотирьох знакових українських художників – Володимира Макаренко, Антона Соломухи, Володимира Стрельникова та Віталія Сазонова. Усі вони здобули визнання ще у 1970-х роках, перебуваючи в Радянському Союзі, однак змушені були працювати в умовах жорсткої цензури та ідеологічного тиску «залізної завіси».

Макаренко Володимир (Volodymyr Makarenko) (нар. 1943) – український художник нон-конформіст. Навчався у Дніпропетровському художньому училищі у майстерні Я. Калашник. Дипломну роботу «У блакитному краю» було знищено, а художника звинуватили у формалізмі та позбавили можливості подальшого навчання в Україні. Переїхав до Ленінграда і вступив до Вищої школи монументального мистецтва ім. Мухіна (1963). Здобув диплом художника монументального розпису (1969) і того ж року став членом неформальної організації художників-нонконформістів, відомої на Заході як «Петербурзька група». Переїхав до Таллінна (1973), де знайомиться та експонується з місцевими художниками. Емігрує до Парижа (1981); отримав Срібну медаль Парижа за мистецьку спадщину (1987). Проводив виставки у Франції, Німеччині, США, Канаді, Швеції; співпрацює з європейськими та американськими галереями. Живе та працює у Парижі.

Макаренко Володимир (Volodymyr Makarenko) (нар. 1943) – український художник нон-конформіст. Навчався у Дніпропетровському художньому училищі у майстерні Я. Калашник. Дипломну роботу «У блакитному краю» було знищено, а художника звинуватили у формалізмі та позбавили можливості подальшого навчання в Україні. Переїхав до Ленінграда і вступив до Вищої школи монументального мистецтва ім. Мухіна (1963). Здобув диплом художника монументального розпису (1969) і того ж року став членом неформальної організації художників-нонконформістів, відомої на Заході як «Петербурзька група». Переїхав до Таллінна (1973), де знайомиться та експонується з місцевими художниками. Емігрує до Парижа (1981); отримав Срібну медаль Парижа за мистецьку спадщину (1987). Проводив виставки у Франції, Німеччині, США, Канаді, Швеції; співпрацює з європейськими та американськими галереями. Живе та працює у Парижі.

Соломуха Антон (1945-2015) – український художник. Народився у м. Київ. Навчався у Київському державному мистецькому інституті на факультеті реставрації ікони. Був зарахований до майстерні академіка Тетяни Яблонської. Здобув диплом художника-монументаліста (1973), іммігрував до Франції (1978). Працює у жанрі нарративно-фігуративного живопису (з 1980-х). Займається фотопроектами (з 2000). Відомий відкриттям нового жанру в сучасній фотографії – «фото-живописі», де у багатофігурних мізансценах фотографічне зображення поєднується з мальовничими пошуками. Жив і працював у Парижі.

Соломуха Антон (1945-2015) – український художник. Народився у м. Київ. Навчався у Київському державному мистецькому інституті на факультеті реставрації ікони. Був зарахований до майстерні академіка Тетяни Яблонської. Здобув диплом художника-монументаліста (1973), іммігрував до Франції (1978). Працює у жанрі нарративно-фігуративного живопису (з 1980-х). Займається фотопроектами (з 2000). Відомий відкриттям нового жанру в сучасній фотографії – «фото-живописі», де у багатофігурних мізансценах фотографічне зображення поєднується з мальовничими пошуками. Жив і працював у Парижі.

Стрєльніков Володимир Володимирович (1911-1981) - живописець, графік, теоретик, педагог. Відвідував студію художника Кишинівського (1930–1936). Навчався в ОХІ у Д. Крайнєва, Т. Фраєрман, П. Волокидіна (1936-1954). З перервою викладав у мистецьких училищах Одеси, м. Херсон, у с. Водички. Учасник ВВВ. Член СГ СРСР (1953). Зробив відкриття "четвертого закону перспективи" (поч. 1950-х). З цього часу до кінця життя активно займався самостійною творчою діяльністю.

Стрєльніков Володимир Володимирович (1911-1981) - живописець, графік, теоретик, педагог. Відвідував студію художника Кишинівського (1930–1936). Навчався в ОХІ у Д. Крайнєва, Т. Фраєрман, П. Волокидіна (1936-1954). З перервою викладав у мистецьких училищах Одеси, м. Херсон, у с. Водички. Учасник ВВВ. Член СГ СРСР (1953). Зробив відкриття "четвертого закону перспективи" (поч. 1950-х). З цього часу до кінця життя активно займався самостійною творчою діяльністю.

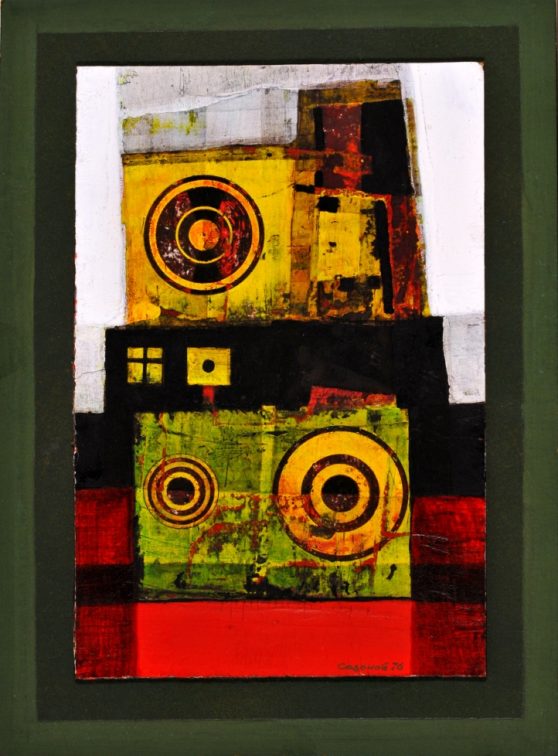

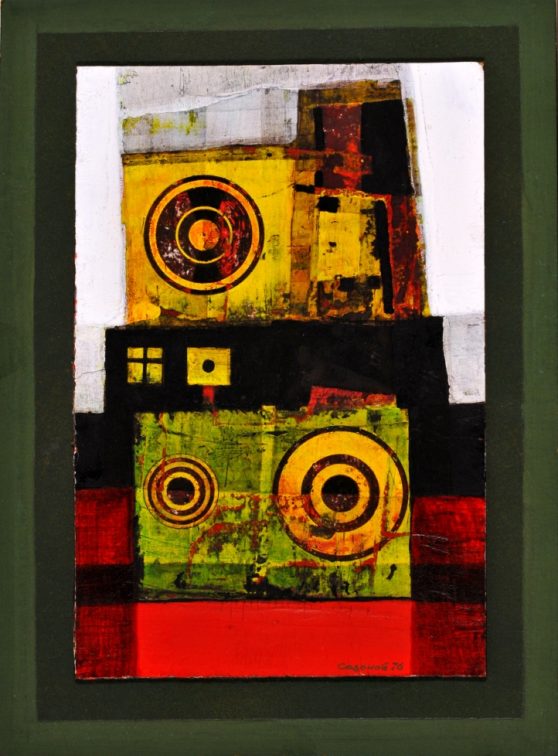

Сазонов Віталій Захарович (1947, Забайкаллі – 1986, Мюнхен). Навчався на історичному факультеті Одеського державного університету ім. І. І. Мечникова, Залишив ОДУ на 4-му курсі. 1967 став займатися живописом, з 1972 – професійно. З 1957 жив в Одесі. C 1980 Жив і працював у Німеччині.

Сазонов Віталій Захарович (1947, Забайкаллі – 1986, Мюнхен). Навчався на історичному факультеті Одеського державного університету ім. І. І. Мечникова, Залишив ОДУ на 4-му курсі. 1967 став займатися живописом, з 1972 – професійно. З 1957 жив в Одесі. C 1980 Жив і працював у Німеччині.

Нонконформістські художники 1980-х років – це митці, які здобули академічну освіту в найкращих художніх навчальних закладах СРСР, де домінував канон «соціалістичного реалізму». Проте з принципових міркувань вони відмовилися створювати полотна на революційні теми або ідеалізовані образи комуністичних лідерів і «героїв праці». Натомість художники звернулися до фігуративного та абстрактного живопису, намагаючись через мистецтво осмислити власне уявлення про «вільний світ».

Особливим джерелом натхнення для художників були успіхи їхніх земляків у французькій столиці, зокрема Василя Кандинського, активного учасника салону Іздебського та групи «Незалежних одеситів», а також Соні Делоне, однієї із засновниць орфізму. Їхній міжнародний успіх ставав доказом того, що українське мистецтво здатне бути частиною світового культурного процесу поза межами радянської ідеології.

Виставка демонструє шлях кожного з авторів до візуальної свободи – від сюрреалістичних мізансцен у дусі Марселя Дюшана та пастишів ренесансних композицій до кольорових площин, що перегукуються з живописом Марка Ротка. Важливу роль у формуванні художньої мови цих митців відіграв Париж, який у 1980-х роках став для них простором творчого звільнення та діалогу з європейським мистецтвом.

Організатори виставки підкреслюють, що проєкт став не лише мистецьким, а й філософським висловлюванням.

«Чи може художник, вихований на радянській пропаганді, бути вільним? Для кожного митця цієї виставки відповідь звучить однозначно: “так!”», – зазначається в описі експозиції.

Саме це питання стало концептуальним стрижнем виставки та об’єднало представлені роботи в єдину розповідь про спротив, вибір і свободу самовираження.

Проєкт у Ukraine House став важливою подією для української культурної присутності у США, представивши американській аудиторії художників, чия творчість народилася на перетині радянського минулого, європейського мистецького середовища та прагнення до внутрішньої свободи.

Виставка відкрита для широкої публіки включно до 19 січня за адресою: 2134 Kalorama Rd NW, Washington, D.C.

В експозиції представлені роботи чотирьох знакових українських художників – Володимира Макаренко, Антона Соломухи, Володимира Стрельникова та Віталія Сазонова. Усі вони здобули визнання ще у 1970-х роках, перебуваючи в Радянському Союзі, однак змушені були працювати в умовах жорсткої цензури та ідеологічного тиску «залізної завіси».

Макаренко Володимир (Volodymyr Makarenko) (нар. 1943) – український художник нон-конформіст. Навчався у Дніпропетровському художньому училищі у майстерні Я. Калашник. Дипломну роботу «У блакитному краю» було знищено, а художника звинуватили у формалізмі та позбавили можливості подальшого навчання в Україні. Переїхав до Ленінграда і вступив до Вищої школи монументального мистецтва ім. Мухіна (1963). Здобув диплом художника монументального розпису (1969) і того ж року став членом неформальної організації художників-нонконформістів, відомої на Заході як «Петербурзька група». Переїхав до Таллінна (1973), де знайомиться та експонується з місцевими художниками. Емігрує до Парижа (1981); отримав Срібну медаль Парижа за мистецьку спадщину (1987). Проводив виставки у Франції, Німеччині, США, Канаді, Швеції; співпрацює з європейськими та американськими галереями. Живе та працює у Парижі.

Макаренко Володимир (Volodymyr Makarenko) (нар. 1943) – український художник нон-конформіст. Навчався у Дніпропетровському художньому училищі у майстерні Я. Калашник. Дипломну роботу «У блакитному краю» було знищено, а художника звинуватили у формалізмі та позбавили можливості подальшого навчання в Україні. Переїхав до Ленінграда і вступив до Вищої школи монументального мистецтва ім. Мухіна (1963). Здобув диплом художника монументального розпису (1969) і того ж року став членом неформальної організації художників-нонконформістів, відомої на Заході як «Петербурзька група». Переїхав до Таллінна (1973), де знайомиться та експонується з місцевими художниками. Емігрує до Парижа (1981); отримав Срібну медаль Парижа за мистецьку спадщину (1987). Проводив виставки у Франції, Німеччині, США, Канаді, Швеції; співпрацює з європейськими та американськими галереями. Живе та працює у Парижі. Соломуха Антон (1945-2015) – український художник. Народився у м. Київ. Навчався у Київському державному мистецькому інституті на факультеті реставрації ікони. Був зарахований до майстерні академіка Тетяни Яблонської. Здобув диплом художника-монументаліста (1973), іммігрував до Франції (1978). Працює у жанрі нарративно-фігуративного живопису (з 1980-х). Займається фотопроектами (з 2000). Відомий відкриттям нового жанру в сучасній фотографії – «фото-живописі», де у багатофігурних мізансценах фотографічне зображення поєднується з мальовничими пошуками. Жив і працював у Парижі.

Соломуха Антон (1945-2015) – український художник. Народився у м. Київ. Навчався у Київському державному мистецькому інституті на факультеті реставрації ікони. Був зарахований до майстерні академіка Тетяни Яблонської. Здобув диплом художника-монументаліста (1973), іммігрував до Франції (1978). Працює у жанрі нарративно-фігуративного живопису (з 1980-х). Займається фотопроектами (з 2000). Відомий відкриттям нового жанру в сучасній фотографії – «фото-живописі», де у багатофігурних мізансценах фотографічне зображення поєднується з мальовничими пошуками. Жив і працював у Парижі. Стрєльніков Володимир Володимирович (1911-1981) - живописець, графік, теоретик, педагог. Відвідував студію художника Кишинівського (1930–1936). Навчався в ОХІ у Д. Крайнєва, Т. Фраєрман, П. Волокидіна (1936-1954). З перервою викладав у мистецьких училищах Одеси, м. Херсон, у с. Водички. Учасник ВВВ. Член СГ СРСР (1953). Зробив відкриття "четвертого закону перспективи" (поч. 1950-х). З цього часу до кінця життя активно займався самостійною творчою діяльністю.

Стрєльніков Володимир Володимирович (1911-1981) - живописець, графік, теоретик, педагог. Відвідував студію художника Кишинівського (1930–1936). Навчався в ОХІ у Д. Крайнєва, Т. Фраєрман, П. Волокидіна (1936-1954). З перервою викладав у мистецьких училищах Одеси, м. Херсон, у с. Водички. Учасник ВВВ. Член СГ СРСР (1953). Зробив відкриття "четвертого закону перспективи" (поч. 1950-х). З цього часу до кінця життя активно займався самостійною творчою діяльністю. Сазонов Віталій Захарович (1947, Забайкаллі – 1986, Мюнхен). Навчався на історичному факультеті Одеського державного університету ім. І. І. Мечникова, Залишив ОДУ на 4-му курсі. 1967 став займатися живописом, з 1972 – професійно. З 1957 жив в Одесі. C 1980 Жив і працював у Німеччині.

Сазонов Віталій Захарович (1947, Забайкаллі – 1986, Мюнхен). Навчався на історичному факультеті Одеського державного університету ім. І. І. Мечникова, Залишив ОДУ на 4-му курсі. 1967 став займатися живописом, з 1972 – професійно. З 1957 жив в Одесі. C 1980 Жив і працював у Німеччині.Нонконформістські художники 1980-х років – це митці, які здобули академічну освіту в найкращих художніх навчальних закладах СРСР, де домінував канон «соціалістичного реалізму». Проте з принципових міркувань вони відмовилися створювати полотна на революційні теми або ідеалізовані образи комуністичних лідерів і «героїв праці». Натомість художники звернулися до фігуративного та абстрактного живопису, намагаючись через мистецтво осмислити власне уявлення про «вільний світ».

Особливим джерелом натхнення для художників були успіхи їхніх земляків у французькій столиці, зокрема Василя Кандинського, активного учасника салону Іздебського та групи «Незалежних одеситів», а також Соні Делоне, однієї із засновниць орфізму. Їхній міжнародний успіх ставав доказом того, що українське мистецтво здатне бути частиною світового культурного процесу поза межами радянської ідеології.

Виставка демонструє шлях кожного з авторів до візуальної свободи – від сюрреалістичних мізансцен у дусі Марселя Дюшана та пастишів ренесансних композицій до кольорових площин, що перегукуються з живописом Марка Ротка. Важливу роль у формуванні художньої мови цих митців відіграв Париж, який у 1980-х роках став для них простором творчого звільнення та діалогу з європейським мистецтвом.

Організатори виставки підкреслюють, що проєкт став не лише мистецьким, а й філософським висловлюванням.

«Чи може художник, вихований на радянській пропаганді, бути вільним? Для кожного митця цієї виставки відповідь звучить однозначно: “так!”», – зазначається в описі експозиції.

Саме це питання стало концептуальним стрижнем виставки та об’єднало представлені роботи в єдину розповідь про спротив, вибір і свободу самовираження.

Проєкт у Ukraine House став важливою подією для української культурної присутності у США, представивши американській аудиторії художників, чия творчість народилася на перетині радянського минулого, європейського мистецького середовища та прагнення до внутрішньої свободи.

Виставка відкрита для широкої публіки включно до 19 січня за адресою: 2134 Kalorama Rd NW, Washington, D.C.

Бефстроганов

Nov. 16th, 2025 09:49 pm В воскресенье, 9 ноября 2025-го, в Париже умер один из важнейших советских и российских художников, основатель соц-арта Эрик Булатов. Ему было 92 года.

В воскресенье, 9 ноября 2025-го, в Париже умер один из важнейших советских и российских художников, основатель соц-арта Эрик Булатов. Ему было 92 года.Вот, что он вспоминал в одном из последних своих интервью перед смертью:

"Это было, когда открылся канал Москва-Волга. И сельскохозяйственная выставка. Отец повел меня туда на праздник, потом в ресторан. Ресторан был плавучий, как речной кораблик, который стоял у берега. Я помню, это был солнечный день, так красиво все было! По потолку бежали солнечные отсветы от окон, от блестящей воды, от волн. Отец взял бефстроганов, а я чего-то стал капризничать. Не знаю, что я стал капризничать, но что-то капризничал. И не хотел есть бефстроганов. Отец очень расстроился. Я понял, что он расстроился, и мне это совсем не было приятно. Тем не менее, я как-то испортил этот день.

Очень скоро после этого началась война. Отец сразу ушел добровольцем и не вернулся. Вот этот несъеденный мною бефстроганов я все время вспоминал. Он какой-то болью застрял во мне. Мне казалось, что все эти несчастья, весь ужас, который потом начался, и голод — все это из-за того, что я не съел тогда этот бефстроганов.

Таким было мое самобичевание. За ту мою капризность надо было заплатить."

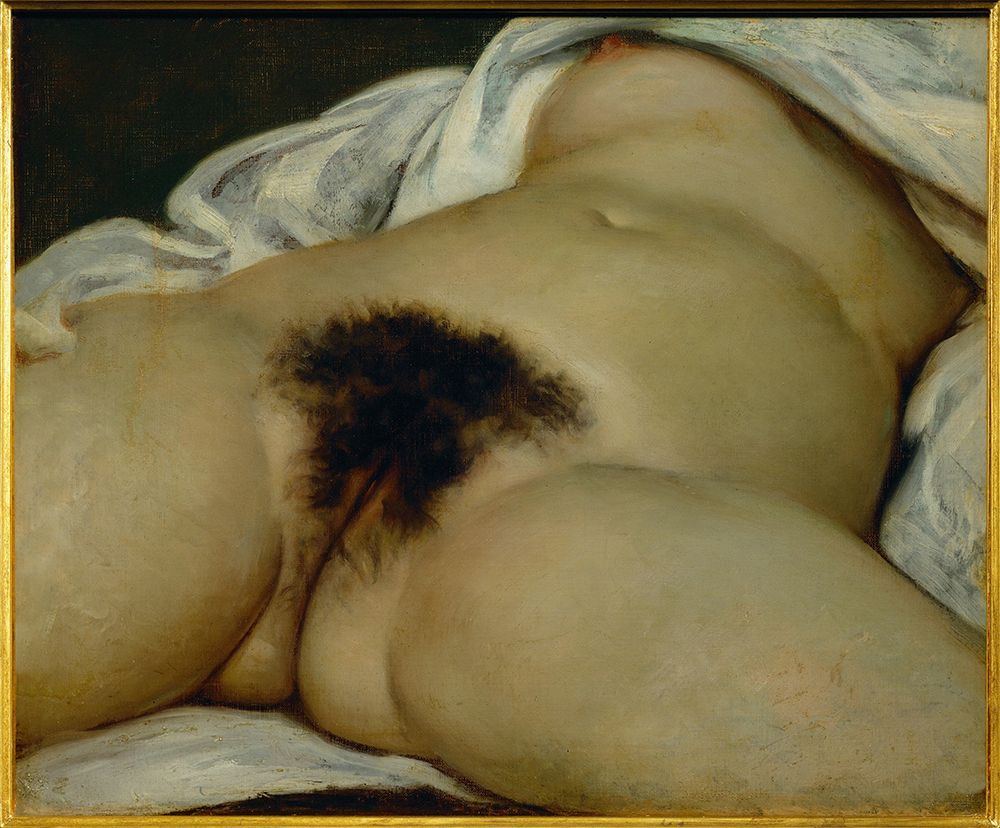

It is understandably difficult to identify the model behind Gustave Courbet’s most famous female nude, L’Origine du monde (The Origin of the World, 1866), since the painting only depicts the cropped torso of a woman, focussed on her genitals. However, recent research by the French literary scholar Claude Schopp, detailed in a book was released by the Paris-based publisher Phébus on 4 October 2018, has named the model with near-certainty as the Opéra ballet dancer Constance Quéniaux, who would have been 34 years old and retired at the time the work was painted.

It is understandably difficult to identify the model behind Gustave Courbet’s most famous female nude, L’Origine du monde (The Origin of the World, 1866), since the painting only depicts the cropped torso of a woman, focussed on her genitals. However, recent research by the French literary scholar Claude Schopp, detailed in a book was released by the Paris-based publisher Phébus on 4 October 2018, has named the model with near-certainty as the Opéra ballet dancer Constance Quéniaux, who would have been 34 years old and retired at the time the work was painted.The painting’s model was previously thought to be Courbet’s lover, Joanna Hiffernan—which seemed strange, as Hiffernan was a redhead, and the pubic hair in the picture is dark. Quéniaux, meanwhile, was noted in contemporary texts as having “beautiful black eyebrows”. She was also the lover of the Ottoman diplomat Halil Şerif Pasha (Khalil Bey), who commissioned the painting.

Schopp was going through a letter from Alexandre Dumas, fils to George Sand dated June 1871 at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF, National Library of France), which included a line that had been previously transcribed in English as: “One does not paint the most delicate and the most sonorous interview of Miss Queniault (sic) of the Opera.” But after examining the handwriting in the original letter, Schopp realised the word “interview” was in fact “interior”.

Another convincing fact is that Quéniaux’s will included a painting by Courbet of camellia flowers that had an open red blossom at its centre, which Aubenas believes may have been a gift from Halil Şerif Pasha. In later life, Quéniaux became a respected philanthropist, which is why Aubenas believes her association with the painting was lost over time.

Короткий Рассказ

Jan. 21st, 2024 08:31 am «Продаются детские ботиночки. Неношеные»

«Продаются детские ботиночки. Неношеные»Эрнст Хемингуэй

«Мечтала о нем. Получила его. Дерьмо».

Маргарет Этвуд

«Легко. Просто поднесите спичку».

Урсула Ле Гуин

«Лучшая месть — прекрасная жизнь без тебя»ю

Джойс Кэрол Оутс

«Лжецы. Удаление матки не улучшает секс».

Джоан Риверс

«Не лучшее время для открытых браков».

«Прочел все имеющиеся в доме книги».

«Установил социальную дистанцию между собой и холодильником».

«Мир никогда не казался таким маленьким».

Мемуары о пандемии коронавируса

«Пришельцы, замаскированные под пишущие машинки? Никогда не слыхал…».

«Последний человек на Земле сидел в комнате. Раздался стук в дверь».

Колин Гринлэнд

«Незнакомец взбирался по темной лестнице: тик-так, тик-так, тик-так».

Хорхе Луис Борхес

Прогулка

Взрыв гнева у дороги, отказ разговаривать на тропе, молчание в сосновом бору, молчание на старом железнодорожном мосту, попытка быть милой по колено в воде, отказ прекратить спор на плоских камнях, яростный вопль на скользком от грязи берегу, рыдания в густом кустарнике.

Лидия Дэвис

Маленькая басня

— Ах, — сказала мышь, — мир становится все теснее и теснее с каждым днем. Сначала он был таким широким, что мне делалось страшно, я бежала дальше и была счастлива, что наконец видела вдали справа и слева стены, но эти длинные стены с такой быстротой надвигаются друг на друга, что вот я уже добежала до последней комнаты, а там в углу стоит мышеловка, в которую я могу заскочить.

— Тебе надо только изменить направление бега, — сказала кошка и сожрала мышь.

Франц Кафка